Dan Oakes

ABC Investigations

February 26, 2021

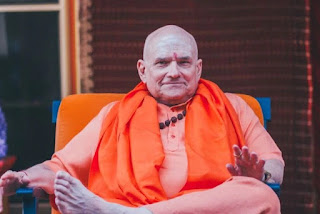

For decades people have flocked to a bucolic ashram in one of Melbourne's most exclusive suburbs to hear the guru spin his folksy brand of Eastern mysticism.

To his loyal followers, 78-year-old Russell Kruckman is Shankarananda: a spiritual master, an authority on meditation, and even a conduit to divinity.

But there is something rotten in his Shangri La.

Content warning: This story contains descriptions of alleged sexual assault.

Over months, Background Briefing has spoken to more than 20 of Kruckman's former devotees.

They have alleged mind control and sexual abuse at the hands of the guru.

They describe him as an abusive narcissist, who has preyed on vulnerable women for decades.

"He believes that he is healing these women with his penis," said Nigel Denning, a psychologist who used to attend the ashram and now provides support to people who have left the community.

Other former devotees say he believes he does not answer to any of the laws of the land in which he lives.

One devotee, Naomi, tells us: "When all of the abuse came to light and there was a hint that it would turn legal and go to court, I said to him, 'What are you going to say if you have to go to court? and he said, 'I'll lie'.

"I said, 'You can't lie in a court of law'. And he said, 'My word's higher than the court of law. I'm God'."

Naomi's story

When Naomi was 14, she and her sisters were introduced by their father to Kruckman, just before he opened the sprawling ashram on a large, leafy block in Mount Eliza in 1996.

Naomi's first impressions of Kruckman's group were not favourable.

"There were people chanting, swaying, doing what I thought were really weird practices, and I saw Russell and he was in monochrome robes," she said.

"My immediate thought was, 'This is a cult'."

Over the years, though, her father and ashram members drew her into Kruckman's group.

She attended sessions, hoping that the guru's teachings would help her overcome the trauma of her past.

"My dad, prior to leaving the family home, was an alcoholic. My mother was extremely violent," she said.

A woman is photographed from behind standing at a window with her hand on the window frame.

Naomi was a teenager when she met Russell Kruckman for the first time.(ABC News: Simon Winter)

People came and went from the ashram, attending classes and sessions, but a core group of Kruckman's devotees lived on site. They were known as the 'ashramites'.

Although she was initially repulsed by the "happy, zealous" acolytes, one day Naomi decided to make the leap and ask if she could move into the ashram. There was a long waiting list, but Kruckman told her she could move to the front of the queue because she was "the professor's daughter".

Naomi packed up her belongings and headed down the freeway from Melbourne to the idyllic surrounds of the ashram, excited about this new chapter in her life.

She received a rude shock. She was put to work chopping vegetables in the ashram kitchen, unpaid, and was told she would have to pay $350 a week to live there.

She was given a schedule accounting for almost every hour from morning to evening.

"I looked at it and I thought, 'How am I going to live my life within that?'" Naomi said.

PODCASTBackground Briefing Logo

From the start, there were things that made Naomi uneasy about ashram life, that did not quite gel with the egalitarian, enlightened image Kruckman liked to portray.

"When you sat at the meal table, no-one was allowed to talk," she said.

"Everyone had to be silent and, you know, in reverence of Russell. If Russell was conducting a conversation or if you were not his chosen kind of person that he wanted to talk to, then you weren't allowed to talk back.

"There was a really strong hierarchical system in the ashram and I very soon realised that I was right at the bottom of that hierarchy. And it was a pretty awful place to be because you were given all the shit jobs."

Over the years, Naomi was burdened with ever-increasing amounts of work.

She says she was ordered to drop out of her postgraduate university course. She complied.

"For me, that was a shock. I had never considered not studying. My life plan was I was going to go from school to university, do my PhD and then get a job," Naomi said.

"I was shocked … I knew that I couldn't say no … so I said, OK"

"After that semester, I stopped university and then quite soon took on some big responsibilities in the ashram. I took over running the kitchen."

She said her relationships, her finances, her friendships, her work, her study, were all eventually controlled by Kruckman.

She and the other ashramites were encouraged by Kruckman to cut themselves off from the outside world.

"Everyone that was not a part of the ashram community, as far as they were concerned, were unconscious and unawakened people and that was a very big put-down," she said.

For most of the decade Naomi lived at the ashram, there were around 40 ashramites living there permanently, with up to 100 people staying there at any given time in dormitories. Hundreds more people flowed through the ashram every week for yoga and meditation classes and other courses.

Kruckman teaches an esoteric strand of Hinduism called Kashmir Shaivism, but according to Naomi, the ashramites were being indoctrinated with one key lesson.

"It was about your relationship with the guru and about surrender," she said.

"And that was a big part of being a yogi or a good disciple. That was what everyone wanted to be. So how much could you surrender to your guru?"

One day, Naomi served Kruckman a salad sandwich for lunch.

"When I went to collect the tray, he pulled my arm and just started kissing me," Naomi said.

"He used to love raw red onion, and all I can remember was the acrid taste of the red onion in my mouth. And I just kind of stood frozen there, just not understanding what had happened. Then he kind of released me and after a certain amount of time, he said 'interesting'."

Naomi was shocked because, like many of the ashramites, she had assumed Kruckman was celibate and asexual.

"He'd already spent 16 years laying the foundations for what he was to do to me when he came on to me and from that point forward," she said.

"This doesn't happen in a vacuum. He has spent all those years indoctrinating me and everyone else, with surrendering, doing what the guru says, not questioning. Everything the guru does is ordained by God. Every single part of his teaching was part of the grooming process. So all he had to do was turn the tap."

Kruckman instructed Naomi to come to his room later that night. Naomi did not want to go down. The thought of it filled her with dread, but she felt she could not say no.

"He text messaged me at 10:30 and said, 'The coast is clear, you can come down,' and I went down. I didn't really know what was going to happen," Naomi said.

"And when I got there, he ushered me into his room, being very clever at making sure no-one was around, no-one could hear us, and he just started kissing me and told me to take my clothes off.

Naomi said Kruckman then forced himself on her.

"I've never experienced anything so repulsive in my whole life. He was an old, fat, bald man and I was a young woman. And I just couldn't understand what was happening. And after that night, I realised that that was something that he was wanting from me and expected from me," she said.

"He said, 'You know, this is a secret between you and me. You can't tell anybody. That's the way Tantra works. It's a secret.'"

Naomi said that after the initial incident, she tried to avoid Kruckman's demand for sex but felt she had no choice but to eventually acquiesce.

"I did everything I could to avoid getting into that situation with him, from pretending I had a headache to saying I had my period to saying I'd just taken a sleeping tablet to saying there's people there," she said.

"Sometimes, in the end, I just knew that I had to go and see him and let him do what he wanted and do just to get it over with, and those were the worst nights of my life.

"I didn't consider myself an overly religious person, but those nights I got down on my hands and knees and did something I'd never do before. I made a deal with God, I said, if you can get me through the night and if you can get me to do those acts with him, then I will be enlightened."

Naomi said over the next few years, she would go to Kruckman for help with her childhood trauma and associated insomnia. Instead, he repeatedly forced himself on her.

"I would go to him, desperate for him to give me a teaching that would help me to kind of get to the source of my trauma. There's something I'm not doing right. There's some teaching that I don't understand," she said.

"I kept seeing it as a shortcoming in me and I would beg him. And his answer was he'd unzip his pants and make me give him a head job. That was his answer to my issues of insomnia and my suffering and my pain."

Naomi wasn't the only one

Tanya-Lee Davies was not pleading for enlightenment when she began attending Russell Kruckman's classes, but she was certainly searching for answers to some of life's bigger questions.

She began following Kruckman when he was still operating in Melbourne's inner city and followed him to Mount Eliza when he opened the ashram.

Like Naomi, Tanya-Lee said she was slowly indoctrinated over the years with the belief that the guru was the guiding light she should follow.

"You believe this person is a direct conduit to God, and I know that that sounds bizarre," she said.

"You trust them, you allow yourself to be vulnerable. You love them in a different way than say you'd love your boyfriend or your mum or your brother or your friends.

"It's a different sort of feeling because you believe that this person has your best interests at heart and that they want to help you become the best person you can become."

Despite the reverence and love she held for Kruckman, Tanya-Lee did have misgivings about some of the things she saw at the ashram as the years rolled by.

"I worried about the lack of privacy. I worried about the lack of boundaries," she said.

"I just started to see these behaviours that didn't seem congruent with somebody that was supposed to be as spiritually evolved as he was."

Despite her doubts, 12 years passed since she began following Kruckman.

Excited about what was a significant milestone in Kashmir Shaivism, Tanya-Lee went to Kruckman to tell him about the anniversary of their meeting.

"I went to hug him, which was pretty normal, and he kissed me on the lips. And I got a real surprise because it was so unusual," she said.

Shocked, Tanya-Lee said she told the guru that she could not have that kind of relationship with him and he replied, "Think of it as an initiation".

"All my safety was immediately just gone, it evaporated, you know," Tanya-Lee said.

Tanya-Lee stayed for another nine years, during which time she says the abuse by Kruckman continued.

"It would range from him wanting to kiss me to doing these things like kissing your neck and putting his tongue in your ear," Tanya-Lee said.

"He had this bathroom where it was sort of out of view and sometimes he'd take me into the bathroom. So if anyone came into the room, they wouldn't be able to see what was happening.

"People would say, why didn't you leave? You've got to understand, I was always entrenched."

For nine years, Tanya-Lee kept the persistent abuse secret from everybody except one other woman at the ashram, who was also suffering her own ordeal at Kruckman's hands.

Background Briefing has spoken to that woman, who alleges an escalating pattern of sexual abuse by Kruckman against her starting in 2007 and including what she describes as a sexual assault in 2013.

Background Briefing has also seen a police statement made by a third woman, who alleges that Kruckman violently raped her in 2010 in his bedroom at the ashram.

She had gone to his bedroom to refill his cookie jar when he pushed her onto the bed and allegedly assaulted her. She said after she made her statement Kruckman was arrested and questioned but not ultimately charged.

Background Briefing has spoken to a number of other women who have alleged behaviour on Kruckman's part ranging from indecent assault to predatory, manipulative sexual practices dating back at least 15 years.

All of the women speak of either feeling powerless to tell Kruckman to stop due to the guru-disciple relationship, or of Kruckman continuing his behaviour even when being told that it was not welcome.

The men's story

It was not only women who fell under the spell of Russell Kruckman at Mount Eliza, and sex was not the only way in which the guru exerted his control over his flock.

Men also flocked to the ashram, lured sometimes by the happy-seeming, attractive young women in Indian-inspired clothing that Kruckman seemed to accumulate there.

Like the women, many of the men who found their way to the ashram were intelligent and well-educated but had something in their lives that made them vulnerable.

Alex Buxton was 22 years old and profoundly depressed when his brother "dragged" him to the ashram for meditation classes.

"I was seeing these kind of bright-eyed, sycophantic devotees, kind of like adoring Russell, chanting and smiling," Alex said.

"I kind of looked at them and went, I'm just not into this. But every time he would do a talk, I found his talks interesting, I found them funny and whatever state I was in, I'd walk away from satsang [the weekly sacred gatherings at the ashram] and something would be going off in my mind that would stimulate a different thought for me."

Soon Alex decided to move into the ashram, alongside Naomi and the other ashramites.

"All of a sudden you were just in this instant community and this instant family and it was interesting and exciting and stimulating. It was quite a sort of liberal scene," he said.

"Russell was into stuff that I was into: he loves sport, American sport, which I was right into. He loved music, especially blues music, which I was right into, he was really funny and quirky and [was] just so quick-witted. I found him sort of riveting to listen to."

Alex's friend Simon Hart was also living at the ashram. He had started yoga classes with Kruckman in the mid-1990s to deal with a back injury. Within two years he had been enticed to live in the ashram as well.

"I thought he was a kindly old grandfather figure. I really loved him when I first met him," Simon said.

"It was only after the five-year period, I started to have friction with him and kind of see cracks in this facade of who he is."

Like Alex, Simon was puzzled to find that Kruckman interfered with his relationships. But he later discovered it was worse than that.

"It turns out that Russell was sexually abusing my partner, and then the next day offering me relationship advice when I went to him to say, 'I think there's something wrong with my relationship and I don't know what it is'. He'd abuse her and then drop her off at my house," Simon said.

"One thing that I feel strongly about now is that the focus of this whole episode has been on the women and what they went through, and it should be because they copped the worst of it. But as men, like we were victims, too. But we're the silent victims. We never had a voice, really."

The big blow-up

By 2014, the ashram had been operating for 18 years and there were dozens of ashramites living on the grounds.

Over the years, Kruckman's predations against female devotees had caused some small ripples, but his secret had remained largely hidden.

But that changed before Christmas of that year. Over a couple of weeks, stories began to emerge of Kruckman having sex with female devotees. It culminated at the Christmas satsang, one of the biggest nights of the year.

In front of a large crowd, Kruckman was accused by some of the devotees of having sex with female followers. Kruckman admitted that he had sex with a handful of women, but he claimed the sex was part of "tantric practices" and was totally consensual.

Behind the scenes, though, the number of women kept growing, and many of them were not necessarily happy with what had happened.

Two devotees wrote a letter to the ashram's board describing Kruckman's behaviour as "institutional sex abuse", and a "horrendous abuse of power".

"It was like one minute it was bubbling underground and the next minute it was on the surface," Tanya-Lee Davies said.

"It was like this tidal wave."

The management committee of the ashram released an open letter, admitting that Kruckman had had "secret sexual relations" with a number of women and saying he was "sincerely apologetic and deeply regretful if his practices have caused hurt or confusion".

The guru himself vowed in a letter that he would stop the behaviour that had caused so much angst amongst his devotees.

"I know people are disappointed and upset. I apologise to them and ask their forgiveness. I want to meet you all and make appropriate amends if you will let me. I am open to talking about a way through, back to love," he wrote.

But according to some of those who stayed, the public display of contrition and remorse was a facade.

Matt* had lived at the ashram for a number of years but was already suspicious about some of what he saw there.

"What I observed at the time was that he didn't seem to have any remorse. He seemed to have hatred, actually, towards the people that had spoken out against him," Matt said.

"It was very much framed as lies and as a power struggle, that they were trying to destroy him."

When Naomi found out that Kruckman had been sexually abusing women other than her, she was shocked.

But she was convinced by Kruckman and his second-in-command, Valerie Angell, known as Devi Ma, to stay at the ashram, even though her sister, Leila, had fled in the wake of the revelations.

"Every time another woman spoke up about being abused, I went to Russell and Valerie, I asked them what happened," Naomi said.

"In every case, they said that the women were lying or they were jealous or it wasn't as bad as they had made out.

"I was so loyal to Russell and Valerie and this is what part of being indoctrinated and being part of a cult is, is that you have to have unwavering loyalty to the leaders."

After it emerged that Kruckman had been abusing other women, Naomi confronted him, telling him that she no longer wanted him to touch her.

"The next time he did it, I said, 'That's it. I'm telling Valerie, I'm telling Devi Ma'," she said.

"We were in Russell's room, me and Valerie and Russell. And I said, 'Devi Ma, Russell has tried to come on to me again and he would stick his tongue in my ear' and stuff like that.

"And he looked at me like he wanted to kill me … and he goes, 'You're a f***ing liar'. And I said, 'No, I'm not lying'.

"And I actually ran and I kind of sheltered behind Valerie and at the same time he's going 'It's not true, it's not true,' to Valerie. And Valerie said, 'I believe her. I believe her, Swamiji. I believe her.'"

'An authoritarian, destructive cult'

Naomi and many other former devotees say they were brainwashed and that the Mount Eliza ashram was a cult with Russell Kruckman as its figurehead.

Nigel Denning, the psychologist who was also an ashram member, treated around 70 former devotees who left the ashram in the wake of the revelations.

He said that many of the features of life at the Mount Eliza ashram correspond with recognised characteristics of cults.

"One of the techniques that Mount Eliza used is something called 'shiva process', which was a way of something called the cult of confession, where you get people to open up and to express all their fears and all their concerns," Denning said.

"What they don't realise is all the disclosures, all the information is being run to the leadership."

Former devotees have told Background Briefing that Kruckman liked his followers to believe that he had some kind of supernatural ability to read peoples' minds when in actual fact he was using information gathered through these shiva process sessions.

"Another aspect of cult life is putting people through lots and lots of menial work, manual work, because you wear people down, you reduce their sleep, you enrich yourself through their labour," Denning said.

Denning ended up speaking with an American called Steve Hassan, one of the world's foremost experts on cults and mind control.

Background Briefing asked Hassan whether he believed the Mount Eliza ashram was a cult, based on publicly available material about what went on there.

"There is ample evidence of behaviour control in this organisation, that is very much in the paradigm of an authoritarian, destructive cult," Hassan said.

Hassan told Background Briefing that he defines such cults as having a pyramid structure, with one person or a group of people at the top, that uses deceptive recruitment and specific mind control techniques that incorporate behaviour control, information control, thought control and emotional control to make people dependent and obedient.

"There is regulation of people's environments. People are discouraged to stay at work or education. They were encouraged to cut off contact, significant time demands, regulated diet, regulated sleep, change of clothing, needing to ask permission for major decisions, rewards and punishment, imposition of rigid rules and regulations, punishment of people who disobey, threats of harm to them or their family," he said.

"[Kruckman] was abusing, in my professional opinion, his authority with the devotees and the followers to the point where he was taking advantage of the women sexually and members financially and basically trafficking them in terms of their labour in order to aggrandise himself and glorify himself."

Former ashramite Matt read a lot about cults and mind control as he tried to extricate himself from the ashram. He describes a series of "aha!" moments as he read the various definitions of cults.

"The most important of all of them in my eyes is this: You can never leave," he said.

"I think the people who are still loyal to Russell have so much been embedded with this phobia of leaving, that if you ever leave, everything will be bad, that they are literally trapped in a kind of cage of the mind."

From within his inner circle, Naomi saw the hold Kruckman had over his devotees.

"He absolutely sees himself as infallible, transcendent, above the mortal realm," she said.

"He sees himself as God. He sees himself as having the qualities of God, omniscient, omnipresent. He really thinks that he is not a mere mortal like the rest of us. And that's how we were encouraged to see him as well."

The search for justice

After the revelations of 2014, half a dozen women came together and sued Russell Kruckman for sexual abuse. They also sued the Mount Eliza ashram for breach of duty of care.

Naomi and her sister Leila were among them. The two sisters and at least one other woman claimed that Kruckman sexually abused them.

At the end of a four-and-a-half-year legal battle, Kruckman settled with the women.

A number of former ashramites also made complaints to the police about Kruckman, including some of the women who were part of the civil action. Kruckman was arrested and questioned, but not charged.

Some women told us the police said they could not proceed with the matter because it would be too hard to gain a conviction. In Leila's case, she said the police were supportive but she was unable to continue with the process due to ill-health.

Psychologist Nigel Denning said part of the problem is the police do not grasp the psychological control Kruckman has over his devotees.

"I worked with an advocate who works in the institutional abuse space and we met with some senior members of the CIB and rape squad up at the Frankston area," Denning said.

"But because the women that were reporting were over 18, they were seen as adults and there was a general lack of interest on the part of the police in really drilling down into the stories.

"There's a recognition in America that people in positions of authority can misuse that for sexual gain and sexual gratification against members of their community. That doesn't exist in Australia, to my knowledge. And certainly, the police had no interest in picking that kind of information up or running with that kind of idea."

Naomi has not gone to the police yet but said that when she was being stalked by members of the ashram after she left, she spoke to a detective and told him her entire story. She said he told her if she wanted to pursue sexual assault charges against Kruckman he would reopen the criminal case. When asked what she is going to do next, she replies: "That's the million-dollar question."

'He should be shut down'

Despite all the trauma and torment allegedly caused by Kruckman, the ashram continues to accumulate new devotees, and the guru has retained some of his most loyal and fierce followers.

Background Briefing has spoken to at least one woman with whom Kruckman continued having a sexual relationship even after he publicly said he would "stop this behaviour", and we have been told there are others.

Background Briefing sent requests for an interview and detailed questions for Russell Kruckman to the ashram but received no response.

To those who left the ashram, it is inconceivable that Kruckman should still be operating as if nothing has happened.

Alex Buxton wants to know why the laws and rules that govern other professions don't seem to apply to spiritual leaders such as Kruckman.

"My biggest concern now is that there's vulnerable people, especially women that could go to the ashram and be exposed to this guy and have a detrimental effect on their whole life," he said.

"There's a real huge loophole in that if you're a doctor, you're a psychiatrist, you're a university lecturer, you're a primary school teacher, there's a code of ethics that you have to abide by in order to be able to practise what you're doing.

"He's a teacher. He's a confidant. In some ways, he's almost like a surrogate parent for people. He's supposed to uphold the highest ideal, and yet he's essentially abusing people and he's allowed to practise. He should be shut down."

Psychologist Nigel Denning believes Kruckman would have been unlikely to stop his behaviour, even after being confronted with the consequences of his actions.

"[If] there's been no severe consequences for his behaviour then, you know, his behaviour will probably have accelerated," Denning said.

"He would have had a smaller pool of victims, but there would be no diminution until he's physically unable because he truly believes, and this is the, you know, the disturbing part of it, he believes his banter."

"He believes that there's something magical and mystical about him and that this is a healing process. You know, this is where these people are dangerous. He's essentially living in a delusional state."

It has taken six years for Naomi to find the strength to speak out about what happened to her at the ashram.

She has one message for anybody who is still at the ashram.

"Leave. Leave as quickly as you can, run," she said.

"Get out of there. Don't waste your life like I did. The quicker you leave, the quicker you can heal and it's going to be hard, but you'll feel a sense of deep relief, knowing when you leave that you've done the best thing that you can do for yourself."

*Name has been changed.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-02-27/mt-eliza-ashram-guru-russell-kruckman-accused-of-sexual-abuse/13191656