Jan 31, 2022

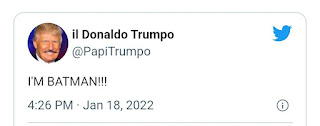

QAnon Followers Think This Fake Mexican Trump Twitter Account Is Real

Jan 30, 2022

ICSA’s Openness to Dialogue: Historical Perspective

ICSA E-Newsletter 28 January 2022 ICSA’s Openness to Dialogue: Historical Perspective Michael D. Langone, PhD

From its founding in 1979, ICSA strove to apply professional perspectives and research to understand and respond to the problems posed by cults. This professionalism has made ICSA open and tolerant, and, consequently, credible. Though there were and continue to be different opinions about how open ICSA should be, the prevailing view has always been that we must not be like cults, which are closed-minded and censor or refuse to engage with those who advocate dissenting views.

The reasons for and importance of openness and dialogue was formally articulated in a document written by the ICSA Board of Directors: “Dialogue and Cultic Studies: Why Dialogue Benefits the Cultic Studies Field.” Historical background can be found on ICSA’s history page, especially “Changes in the North American Cult Awareness Movement.”

ICSA’s openness to dialogue can sometimes be difficult to reconcile with ICSA’s mission of helping those adversely affected by cultic involvements. Former members, especially those who have been traumatized, may feel discomfort -- sometimes revulsion -- when ICSA’s openness to divergent views exposes them to people with positive views of cults or even of religion in general. Openness may also challenge parents and helping professionals who are focused on ameliorating harm. Conversely, some academicians may interpret ICSA’s focus on cult-related harm as an anti-religious bias.

Because ICSA is open to diverse and conflicting views, ICSA cannot please “all the people all the time.” Some degree of tension and discord, therefore, is unfortunately unavoidable. This tension can be challenging, but it can also enhance learning and thinking creatively about cult-related problems.

ICSA is unique because it brings together in a coherent and substantial way international constituencies of victims, families, helping professionals, and researchers. The diversity within ICSA promotes an environment that is conducive to thinking broadly about the subject and to learning from those one might not ordinarily encounter. “Stress-testing” our opinions is a hallmark of critical thinking.

ICSA has tried to minimize the strain that openness can cause in the following ways:

To provide historical perspective, this report lists events and activities that reflect ICSA’s professionalism and history of openness and dialogue with religious persons, academicians of all perspectives, and cult members. (For clarity we will use “ICSA” for those time periods when the organization was called “AFF” – American Family Foundation. The name was changed in 2004.)

Thus, many scholars and professionals who study and research cultic groups (what they prefer to call new religious movements) and who once dismissed ICSA’s reports of cult-related harm now learn from and engage in productive dialogue with ICSA professionals and scholars and the victims who inform ICSA’s perspectives. Members of the ICSA network also learn from this dialogue and continue to develop educational and treatment interventions that consider complexities and variations that were not appreciated during ICSA’s early days. Dialogue does not mean that abuses are condoned. On the contrary, dialogue makes more people aware of abuses in groups. Dialogue also makes more people aware of the ways in which simplistic thinking can generate confusion and unnecessary polarization.

For example, dialogue has made clear that NRM scholars ask different questions from ICSA professionals and scholars. The former may know that harm exists, but they do not focus on it. The latter may share concerns regarding the need to respect protected freedoms of minority groups, but they mainly see people whom such groups harm. Dialogue helps everybody better understand the phenomenon, including the potential for abuse.

To conclude:

International Cultic Studies Association, Inc. PO Box 2265

|

Meth And Me

Jan 28, 2022

The Dark Side of Mother Teresa Mother Teresa, A Saint or a Fraud?

CultNEWS101 Articles: 1/28/2022 (Bhakti Marga, Swami Vishwananda, Podcast, Germany, Islamic Marriage Laws, Conspiracy Theories)

"The Bhakti Marga sect has its headquarters in the Taunus, and its guru, Swami Vishwananda, is worshiped as a god. But again and again dropouts report abuse of power in the ashram - and sexualised violence. This podcast investigates the allegations.

The Bhakti Marga sect has its headquarters in Springen / Heidenrod, a rural area in the Taunus. Her guru Swami Vishwananda is worshiped as God by his followers. What he promises is unconditional love - Just Love. But for many years, dropouts have repeatedly reported manipulation, brainwashing, abuse of power - and sexualized violence that Vishwananda did to them. These warnings are not taken seriously - and the Hindu-Christian faith community continues to grow rapidly, worldwide. In August 2021, Bhakti Marga bought the "Seepark", an old conference hotel, in Kirchheim, Hesse. The communities of Heidenrod and Kirchheim are happy about the ashram operation. Also because the international guests who visit the two German ashrams to be blessed by the guru, flush money into the community coffers. In six episodes, Marlene Halser and Stefan Bücheler investigate the allegations, talk to those affected and ask those responsible why the warnings are not taken seriously. Also they ask: who is this guru, who is Vishwananda? And how did a small religious community become a huge, international company?

A six-part documentary podcast by Hauseins and Hessischer Rundfunk."

Washington Post: For the sake of a visa, I was forced into marriage in Arizona — at age 15

" ... Soon everyone started hugging and saying "mubarak" — congratulations. My heart sank. I realized I had just been forced into a marriage proposal, or "rishta" — a prelude to a "nikah," or Muslim wedding — to a man who needed to stay in the United States when his visa expired. He was seven years older than me. I'd never met him.

The nikah, a religious contract, is not legally recognized under U.S. marriage law. But Arizona's marriage law and loopholes in U.S. immigration law meant my family still had avenues by which they could exploit and force me — a U.S. citizen and a minor — into marriage.

Marriage before age 18 is legal in 44 of 50 states, according to Unchained at Last, an organization working to end child marriage in the United States. In states with no age minimum, children as young as 10 have been forced into marriage. At the time of my engagement, the legal age of consent to marry in Arizona was 15. (Now it's 16 with parental permission or legal emancipation.)"

" ... How do people come to believe in conspiracy theories? It's a question Penn Integrates Knowledge University Professor Dolores Albarracín has been thinking about for decades.

"I grew up in Argentina in the '70s, during the Dirty War that eventually led to the disappearance of 30,000 Argentines. The climate within the dictatorship was such that you couldn't really speak, and for a family that was politically involved such as mine, you were instructed to not say anything," recalls Albarracín. "That piqued my interest in secrecy, and in how people make inferences about events that have presumably been covered up, particularly when there is no evidence."

As a social psychologist and communication scholar who studies attitudes, persuasion, and behavior, Albarracín has researched what happens when fringe ideas become consequential for society. "That's what we're seeing with conspiracy theories today," she says. "Nobody can deny now that these are wildly impactful and really problematic."

In a new book, "Creating conspiracy beliefs: How our thoughts are shaped," Albarracín and co-authors Man-pui Sally Chan and Kathleen Hall Jamieson of Penn and Julia Albarracín of Western Illinois University drill down into the phenomenon. Analyzing empirical research conducted on real-world examples of false plots—the alleged sex-trafficking ring Democrats ran out of a pizza parlor, the so-called deep state that undermined Donald Trump's presidency—the team pinpoints two factors that have driven recent widespread conspiracy theories: the conservative media and societal fear and anxiety."

News, Education, Intervention, Recovery

Intervention101.com to help families and friends understand and effectively respond to the complexity of a loved one's cult involvement.

CultRecovery101.com assists group members and their families make the sometimes difficult transition from coercion to renewed individual choice.

CultNEWS101.com news, links, resources.

Cults101.org resources about cults, cultic groups, abusive relationships, movements, religions, political organizations and related topics.

Selection of articles for CultNEWS101 does not mean that Patrick Ryan or Joseph Kelly agree with the content. We provide information from many points of view in order to promote dialogue.

Please forward articles that you think we should add to cultintervention@gmail.com.