Cult mediators tell us about their most dangerous cases—from finding their house covered in blankets to helping recruits break free from groups where babies were breastfed by mothers high on acid.

Shamani Joshi

MUMBAI, IN

March 30, 2021

Cults can get super weird. They can be abusive, destructive and even life-threatening. They can also be endlessly fascinating.

A social group characterised by their extreme belief or reverence towards a particular leading figure or object, cults aren’t by definition dangerous. But, history has taught us time and again that people who believe violence is an act of love, or that they’re the chosen one to lead the otherwise doomed humanity, or that their leader is actually an alien, probably have issues that need resolving.

In a world full of distress and disease, getting sucked into a cult that offers peace and the promised land is surprisingly easier than it seems. What is not easy, though, is getting out and helping others get out too. We spoke with some cult interventionists and deprogrammers on how they help people break away after having broken away themselves—and the repercussions the work has on their lives.

Joe Kelly

I was involved with two groups in the 70s. One was a group called Transcendental Meditation or TM, that was run by a Hindu guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who became famous for being the Beatles guru. Here, we went from a simple 20-minute meditation technique to being convinced we could levitate for world peace.

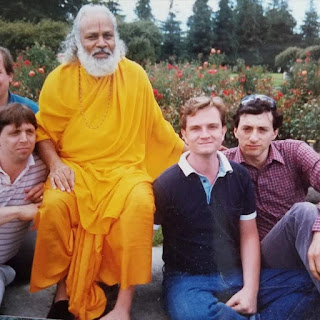

Simultaneously, I was studying comparative religions, and was especially fascinated by Hinduism. I met a man—who I thought was my true guru—named Swami Prakashanand Saraswati, who had a group called the International Society of Divine Love. In the 1980s, he took a group of us from TM and established an ashram in Philadelphia, which was more structured and rigid. Some of its members even sued Maharishi for millions of dollars for being a fraud. Swami Prakashanand then used the money to set up a temple outside of Austin, Texas, called Barsana Dham. But the Swami was eventually convicted of abusing his follower’s children, though he ran back to India where he was protected.

After that, the group’s attorneys suggested we attend this conference where ex members of cults talk about their experiences, so we could understand how to evaluate whether someone is a spiritual guru or a conman. That’s when I first understood the psychology and sociology behind these groups, and decided I’d use my experiences to take apart the structures of belief for other people who had gravitated towards cults.

People join cults if they are dissatisfied with their family, or want to find their own individuality, and such groups make them believe they will help you realise your true potential. One of the most challenging cases I’ve worked on was with a group that encouraged channeling, which is the concept that there is a world of dispossessed spirits that can educate the people of this world, and give you knowledge to live a better life.

But what they taught was that the use of drugs like ecstasy and LSD could help you gain this knowledge. Their approach was to gain more monetary benefit from the world, and they believed that through positive thinking and believing in prosperity, you can change your alignment with the universe, and it would bestow wealth upon you. It was led by a woman named Katherine Holt, who said she was channeling a spirit from the 17th century of a man named Father Andre, who was theoretically a mystic. She had about 30 followers, and would cause people to couple or decouple. She would ask them to do ecstasy, or have sex with people other than their spouses. I began working with a man named Mark, who had married a woman in the group. While in session, his wife was told to have sex with another man upstairs, while Mark could hear them. The leader told Mark that despite what he was hearing and feeling, he had to separate from that emotion. That he would only be free if he let go of the ego and ownership he felt for his wife, and refused to live by the norms of the society. He was tripping on drugs, but was told not to feel the emotions he was feeling.

At that point Mark realised there was something very wrong there. He went to his parents, who contacted me through the Cult Awareness Network. His dilemma was that his wife and child were in the group, and that child was being breastfed by a mom using LSD and ecstasy. We developed a strategy to reach out to the wife. Her family had a wedding in New England, so we went there. The cult told her to stay away from her husband, who was “evil” because he’d left the group. I was supposed to make him feel calm and try to help his wife see how wrong the group was. But, unbeknownst to me, my mentor had organised for Mark to take his child and move to a safe house in Colorado. It culminated in a long legal battle for custody, but eventually the group’s leader was arrested and the wife left.

Some of the most difficult cases for me are the ones that involve a family. Once there’s a romantic influence or friendship with other members of the cult, it becomes more difficult to break them out of it.

Patrick Ryan

I saw Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on a TV show, and got involved with him when I was 17. I spent five years at his university, where we were told things like we could walk through walls to save the world. Since his followers were Nobel Prize winners in physics and governors, we believed these claims. We did 22-hour-long meditations which pushed people to extreme points, many of them even jumping out of windows. Maharishi would also send people into war zones in Iran and Mozambique, often putting them in danger. Over time, I realised that despite everything, I couldn’t in fact levitate or walk through walls. So, I sued him for fraud and negligence.

Pat Ryan Transcendental Meditation

After doing cult mediations for 38 years, I can tell you that while models are important tools to assess the approach of cult interventions, there is no one method to help someone. One of my most important learning experiences was in the early 2000s. I was in Australia to help a member of the Church of Scientology. The Church has a policy that they have to be against someone trying to “expose” them or telling their members to leave. So they had two private detectives follow me from my house in Philadelphia to Australia.

On my last night in Australia, I was served a lawsuit which said I had verbally molested a 17-year-old woman, and that she had demanded a restraining order. I had never met the woman in my life, but what they wanted to achieve through this is to frame a media narrative to affect my credibility. Also, according to Australian law, if I was at a restaurant and this woman walked in, I could get arrested. I had to fight a long legal battle, and ultimately, the judge ruled that I wasn’t guilty. But the church did everything to stop me.

Once, I was flying to Australia to attend my hearing and decided to carry a box of pancake mix when I was stopped at the airport. Turns out, the church had tipped them off saying I was a drug courier. When the authorities opened my bag, they saw white powder all over my stuff because the pancake mix had popped open. But after I told my story to the interrogating agent, he gave me a ten year visa to work in Australia, so even that backfired for the church. When dealing with the church, I’d have armed members parked in front of my house in Philadelphia, blankets covering all my windows from the outside and even people pressing their hands on my door’s keyhole so I was cut off from the outside world.

That’s also when I realised that instead of criticising a cult to its members, I needed to find a way to make them feel heard, especially by their family. If you can appreciate what I like, then you have a right to criticise it. So what I try to do is teach families why people find something beautiful in the cults they join.

In some cases, the family themselves would push people to join cults. I was doing an intervention with a young woman who was part of a martial arts cult, where the leader was sexually abusive. But in the middle of the session with her mother and me, she screamed, “Oh you think he’s bad? Well, dad fucked me.” We had to stop the session right there, and that’s also where I learnt that I had to interview multiple family members before approaching the person who got influenced into a cult.

Joseph Szimhart

I participated in a series of cult-like organisations based on theosophy, the main one being the Church Universal and Triumphant (which was later exposed as a doomsday cult), in the 70s. My first wife divorced me in 1979, since most of my mental time was going towards the cult. As a result, I grew disillusioned with the group. After I quit, my former group members would ask me why. When I told them, they quit based on my information, though they had been in it for longer. That’s when I realised how I could use my experience to help other cult members.

I’ve been in the field for over decades, and worked with people across the world, from the Rajneesh Osho group in Oregon to the Brahmakumaris in Kerala. I have participated in cases where a cult member was kidnapped by their family and kept against their will for many years to make sure they break free of the cultic influence. Those cases are always a challenge because you could end up in jail.I stood trial for a case like this in 1993, but was acquitted of all charges.

The people are also usually very angry and don’t want to talk, so I have to get them to trust me to talk. I had a few cases with a martial arts organisation called Chung Moo Quan, and got several of their instructors to leave. The leader, Master John C. Kim, came to the U.S. claiming he was an Asian martial arts champion and had a title that never existed. He was a middle-aged man with some skills in martial arts, so he set up professional looking schools. He’d recruit members from these schools to enrol in instructor courses, which were sometimes upto $100,000. He had a way of convincing these young people that he had special powers that could harm people without touching them, and he would have these secret meetings with the members, making them feel very special. He formed a cult of these instructors loyal to him in Boston, Houston and Chicago. These people would cut off communication from their families, would go to classes constantly, get just three or four hours of sleep, and put on a lot of weight because of a diet meant to make them “look strong”. They even got beards to look threatening.

The cult leader had an initiation process to prove his followers’ loyalty by putting them in a chokehold and asking them if they’d die for their group. If people passed out in the chokehold, he’d accept them. The members thought he had magical powers so they wouldn’t threaten him. But when the group found out about me, they put out posters vilifying me. After I helped expose them on a television show, they were raided by the government. The group sued me and threatened me verbally several times. An IRS agent even told me they had a hit out on me. I don’t have bodyguards, a gun or even insurance, because most companies see you as a liability.

I have also done interventions with leaders. One was a guy who called himself Paa, which was short for Padmasaaha. He thought he was the reincarnation of Satya Sai Baba, who was a big religious leader in India. But Paa was just a fake magician who claimed he was doing “miracles''. I did an intervention when he had only one member. I acted like I was interested in his religion and interviewed him on camera. But not all interventions help, and he ended up controlling about 30 people.

Follow Shamani on Instagram and Twitter.

https://www.vice.com/en/article/3anxnw/former-cult-members-help-escape-exit-counsellor-intervention-conspiracy-theories

No comments:

Post a Comment