Scientology’s unique manipulations of language seduced the novelist Sands Hall and kept her bound to the church.

Michael Friedrich

Michael Friedrich

The Nation

April 12, 2018

In 1986, after years of illness, Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard died, leaving the church to his key deputy, David Miscavige. Under its new leader, Scientology changed its image dramatically: Hubbard’s absurd cravats and trademark leer gave way to Miscavige’s gleaming business suits and beaming professional smile. Former leaders were euphemistically “rehabilitated.” Small and secretive gatherings blossomed into celebrity engagements in Sheraton Hotel conference rooms. In a word, the church went corporate.

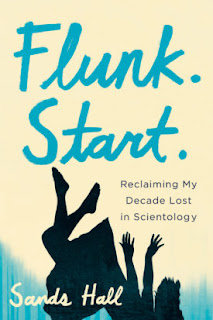

One thing that makes Scientology uniquely American is its amalgamation of corporate and authoritarian modes of social control. “[P]art of what made me get out had been observing that increasingly corporate mindset,” recounts the novelist Sands Hall in her intriguing new memoir, Flunk. Start. Reclaiming My Decade Lost in Scientology. “This is ironic, of course, considering the authoritarian mentality of the Church under Hubbard, but most of those years I managed to stay unaware.” How this combination attracts untold thousands of members—to what is, by most accounts, a cult—has received much attention in the decades since Scientology’s founding in the early 1950s.

Margaret Thaler Singer, an expert on the psychology of cults, believed that no one is impervious: “Any person who is in a vulnerable state, seeking companionship and a sense of meaning or in a period of transition or time of loss, is a good prospect for cult recruitment,” she wrote. Flunk. Start. concerns the way that one ordinary, wayward, middle-class kid found herself in just such a state. And with its keen attention to the language and tactics of the church, Hall’s memoir is unique among the assortment of Scientology reports and exposés, offering insight into the certainties that its subjects gain. Even more strikingly, though, her initiation serves as a symbolic social experience: It reminds us of the American bourgeois conviction, resurgent in our uncertain times, that we can purchase peace of mind—no matter the cost to companions, community, or open society.

The first section of Flunk. Start. moves, chapter by chapter, between the events that attracted Hall to the church and those that separated her from it. The form establishes the split consciousness that governs the rest of the book. Hall’s telling alternates between wisdom and cliché, between moments of avid awareness and banal bromide. When we meet her, in the early ’80s, she’s a “Course Supervisor” on Hubbard’s texts, albeit one with growing doubts about the church’s treatment of its members. “Flunk” and “Start,” we learn, are terms that the church uses to correct practitioners during training exercises: The instructor responds to an error with a dispassionate “Flunk,” while “Start” signals the student to begin again. These terms also come to represent Hall’s abortive search for a sense of purpose.

Hall’s search originated in the neuroses of her middle-class family. The Halls were special, they taught her; they were “proud artists: bohemians.” They were also irreligious. Sure, they filled their Squaw Valley, California, home with Tibetan Buddhist artifacts and Mexican milagros, but the message was clear: There’s “nothing there in which one actually believed.” Her father, Oakley Hall, was a prolific novelist, and according to his daughter, the family was “its own kind of cult.” Their literary life primed her for the power of the word. Culture was the Hall family’s creed: “Television was a waste of time; books provided all needed entertainment…. Theater was an excellent source of culture…but musicals were for underachievers. Tennis was a terrific game, but only morons watched football.” Hall’s mother bought her cans of meal replacement when she grew chubby; her father criticized the Christian allegory of her beloved C.S. Lewis novels (“Stop reading fluff!”). Confronted with this set of expectations, who could hope to measure up?

Nor were the mundane manipulations of family life much help for Hall, the second child of four. In the shadow of her eldest brother, Tad, a celebrated playwright, she adopted a series of identities: actor, folk singer, writer. Like so many twenty somethings, she struggled with a “base need for approval.” In college, Hall starved herself for a role in a musical: “for months I ate nothing but carrots and Juicy Fruit gum, farting all the while.” She dabbled, too, in harder stuff. Hall presents all this as symptomatic of her “pilgrim soul”—a restless search for meaning that animated her life. Tad, who “radiated brilliance, confidence, power,” was her sole semblance of an anchor. “I had shaped myself around his example—in some ways against it…. I was grateful for that lantern glinting ahead amid the looming trees.” Then, one drunken night, after a fight with his wife, Tad took a tragic fall—or perhaps a leap—from a bridge and suffered a debilitating brain injury. “I lost my brother, my leader, my model,” Hall writes, an event that “spun me directly toward the Church.”

Hall officially joined the Church of Scientology in the late 1970s, after moving to Los Angeles and beginning a relationship with Jamie Faunt, a jazz-fusion bassist who traveled among a circle of “Operating Thetans,” or enlightened beings in the church. If she initially wasn’t too keen on Scientology (or jazz fusion), she certainly was keen on Faunt, whose appearance afflicts her prose with gooey clichés. She first noticed his “full lips,” which over the course of the book never diminish in their fullness. And don’t get her started on his skin, which we learn—and relearn—was “smooth as marble.” Another person might have backed away slowly when Faunt began to drone on about his recent “intensive” (a rigorous counseling session) at Scientology’s “Advanced Org” (the church’s iconic blue building in LA), which examined his “Reactive Mind” (the part that’s filled with troubled memories). But Hall couldn’t keep her eyes off his “rock-star” looks.

One problem with Flunk. Start. is that, while Hall fitfully dissects her own shame and dependency, she often seems too enraptured by romance to make much sense of her journey. The problem isn’t just a deficit of irony or style; it’s the whole sentimental paradigm that the book suggests, whereby a momentary swoon, scavenged from the breathy bits of D.H. Lawrence, can soften a rash relationship of manipulation and abuse—the notion that romance is redeeming in itself. Today, this view continues by way of commercial narratives that promise (and, of course, fail) to fulfill our desires for love and belonging and personal identity, if only we spend enough. An organization like Scientology can pick up precisely where such promises disappoint.

Scientology’s special manipulations of language seduced Hall and kept her bound to the church. Although, at first, she was skeptical of the “Standard Tech”—Hubbard’s official writings—it eventually came to shape her life. When Faunt’s friend explained the “thetan,” or spirit, as a being that is “aware of being aware,” Hall was intrigued: “I liked that very much. It tied in with my meditating efforts.” Later, Faunt introduced her to the concept of the “overt,” a transgression against the ethics of the church. “Not an adjective. A noun,” he explained. “This kind of clarity of language, common to Scientologists, I found very appealing,” Hall writes. Studying words during the church’s “auditing” process made language a “teeming garden of possibilities,” but she also saw the problem:

Language connects people, of course, binding us into a uniquely shared world, while also serving as a barrier, separating us from others. It would take a long time to realize how Scientology’s vocabulary, its nomenclature, abetted such binding, and how purposeful Hubbard had been in creating it. I knew then only that the orderly aspects of the religion were deeply appealing, helping me sort through a terrible, consuming confusion.

Reflecting on the way that Scientology’s language circumscribed her thought, Hall invokes 1984, but it’s more as though Orwell’s Newspeak had conceived a ghastly child with a Walmart employee handbook. Language is the vehicle for both the church’s tyrannical mode and its corporate flourishes. Consider this scene where Faunt, now Hall’s husband, drags her before an “Ethics Officer” named Marty to unspool their conjugal woes. Hall invests it with the same droll energy that makes the sci-fi dystopia of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We feel hilariously familiar to anyone who has ever endured a big-box retail training session, with all its bizarre jargon:

Marty looked grave. Jamie [Faunt] leaned forward. “It’s a classic case of Potential Trouble Source. She’s connected to people opposed to Scientology, she’s rollercoastering; she gets better, she gets worse. She’s got a Suppressive Person on her lines. Probably two!”

The phrase “on her lines” made me think of a cobweb, a spider crouched in wait. But it had to do with “comm lines”: those with whom I communicated.

Marty moved his concerned eyes to meet mine. “Who’s invalidating you? Who doesn’t want you to thrive?”

“Her parents!” Jamie said.

In the end, Hall’s focus on this “cobweb” of intimate entanglement is what makes Flunk. Start. compelling—and different from other, more extraordinary accounts of abuse in Scientology’s upper echelons. Lawrence Wright’s Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief, for example, concentrates on the experiences of celebrities like the filmmaker Paul Haggis, who slowly became aware of the church’s sensational cruelties of forced labor and “disconnection” from family, and former church executives like Mike Rinder, whom Miscavige and his deputies routinely beat up when things went awry.

By contrast, Flunk. Start. is most revealing in its depiction of Scientology as just one of many expressions that the American search for selfhood can manifest. Sharing her experience with others convinces Hall that hers is “simply a version of a journey taken by most of us at some point in this life.” It’s not so different, she writes, from other sources of shame—“the decade in the terrible marriage, the years lost to Oxycontin, the time in an ashram agreeing to and participating in sexual coercion”—and “we wouldn’t be who we are without having had those years and learned those lessons in our particular underworlds.” Part of what makes Hall a sympathetic narrator is that she’s divided, ambivalent about the church’s teachings, always aching for an excuse to exit. She’s like a hostage holding herself at gunpoint.

Finally, she has to figure out her own escape. Miscavige’s corporate gloss provided the alibi she needed. A middle-class kid in a middle-class cult, Hall had middle-class resources at her disposal: a family to stay with, an inheritance to collect, the means to go to graduate school (rather than going through the “deprogramming” that others often require). She got an MFA from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The passion for language that the church inspired has found a deeper channel as she became a novelist and professor of writing. Her debut novel, Catching Heaven (2000), concerns two sisters who face their own transformative conflicts and emerge the wiser. Literature serves as the symbolic inverse of a system like Scientology, rewarding close reading with a multiplicity of understandings—rather than exactly one. Having “flunked” a period of life, Hall got a chance to “start” anew. Of course, she didn’t invent this cycle of unhappiness, self-indulgence, and redemption. More than anything, she’s a product of it.

April 12, 2018

In 1986, after years of illness, Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard died, leaving the church to his key deputy, David Miscavige. Under its new leader, Scientology changed its image dramatically: Hubbard’s absurd cravats and trademark leer gave way to Miscavige’s gleaming business suits and beaming professional smile. Former leaders were euphemistically “rehabilitated.” Small and secretive gatherings blossomed into celebrity engagements in Sheraton Hotel conference rooms. In a word, the church went corporate.

One thing that makes Scientology uniquely American is its amalgamation of corporate and authoritarian modes of social control. “[P]art of what made me get out had been observing that increasingly corporate mindset,” recounts the novelist Sands Hall in her intriguing new memoir, Flunk. Start. Reclaiming My Decade Lost in Scientology. “This is ironic, of course, considering the authoritarian mentality of the Church under Hubbard, but most of those years I managed to stay unaware.” How this combination attracts untold thousands of members—to what is, by most accounts, a cult—has received much attention in the decades since Scientology’s founding in the early 1950s.

Margaret Thaler Singer, an expert on the psychology of cults, believed that no one is impervious: “Any person who is in a vulnerable state, seeking companionship and a sense of meaning or in a period of transition or time of loss, is a good prospect for cult recruitment,” she wrote. Flunk. Start. concerns the way that one ordinary, wayward, middle-class kid found herself in just such a state. And with its keen attention to the language and tactics of the church, Hall’s memoir is unique among the assortment of Scientology reports and exposés, offering insight into the certainties that its subjects gain. Even more strikingly, though, her initiation serves as a symbolic social experience: It reminds us of the American bourgeois conviction, resurgent in our uncertain times, that we can purchase peace of mind—no matter the cost to companions, community, or open society.

The first section of Flunk. Start. moves, chapter by chapter, between the events that attracted Hall to the church and those that separated her from it. The form establishes the split consciousness that governs the rest of the book. Hall’s telling alternates between wisdom and cliché, between moments of avid awareness and banal bromide. When we meet her, in the early ’80s, she’s a “Course Supervisor” on Hubbard’s texts, albeit one with growing doubts about the church’s treatment of its members. “Flunk” and “Start,” we learn, are terms that the church uses to correct practitioners during training exercises: The instructor responds to an error with a dispassionate “Flunk,” while “Start” signals the student to begin again. These terms also come to represent Hall’s abortive search for a sense of purpose.

Hall’s search originated in the neuroses of her middle-class family. The Halls were special, they taught her; they were “proud artists: bohemians.” They were also irreligious. Sure, they filled their Squaw Valley, California, home with Tibetan Buddhist artifacts and Mexican milagros, but the message was clear: There’s “nothing there in which one actually believed.” Her father, Oakley Hall, was a prolific novelist, and according to his daughter, the family was “its own kind of cult.” Their literary life primed her for the power of the word. Culture was the Hall family’s creed: “Television was a waste of time; books provided all needed entertainment…. Theater was an excellent source of culture…but musicals were for underachievers. Tennis was a terrific game, but only morons watched football.” Hall’s mother bought her cans of meal replacement when she grew chubby; her father criticized the Christian allegory of her beloved C.S. Lewis novels (“Stop reading fluff!”). Confronted with this set of expectations, who could hope to measure up?

Nor were the mundane manipulations of family life much help for Hall, the second child of four. In the shadow of her eldest brother, Tad, a celebrated playwright, she adopted a series of identities: actor, folk singer, writer. Like so many twenty somethings, she struggled with a “base need for approval.” In college, Hall starved herself for a role in a musical: “for months I ate nothing but carrots and Juicy Fruit gum, farting all the while.” She dabbled, too, in harder stuff. Hall presents all this as symptomatic of her “pilgrim soul”—a restless search for meaning that animated her life. Tad, who “radiated brilliance, confidence, power,” was her sole semblance of an anchor. “I had shaped myself around his example—in some ways against it…. I was grateful for that lantern glinting ahead amid the looming trees.” Then, one drunken night, after a fight with his wife, Tad took a tragic fall—or perhaps a leap—from a bridge and suffered a debilitating brain injury. “I lost my brother, my leader, my model,” Hall writes, an event that “spun me directly toward the Church.”

Hall officially joined the Church of Scientology in the late 1970s, after moving to Los Angeles and beginning a relationship with Jamie Faunt, a jazz-fusion bassist who traveled among a circle of “Operating Thetans,” or enlightened beings in the church. If she initially wasn’t too keen on Scientology (or jazz fusion), she certainly was keen on Faunt, whose appearance afflicts her prose with gooey clichés. She first noticed his “full lips,” which over the course of the book never diminish in their fullness. And don’t get her started on his skin, which we learn—and relearn—was “smooth as marble.” Another person might have backed away slowly when Faunt began to drone on about his recent “intensive” (a rigorous counseling session) at Scientology’s “Advanced Org” (the church’s iconic blue building in LA), which examined his “Reactive Mind” (the part that’s filled with troubled memories). But Hall couldn’t keep her eyes off his “rock-star” looks.

One problem with Flunk. Start. is that, while Hall fitfully dissects her own shame and dependency, she often seems too enraptured by romance to make much sense of her journey. The problem isn’t just a deficit of irony or style; it’s the whole sentimental paradigm that the book suggests, whereby a momentary swoon, scavenged from the breathy bits of D.H. Lawrence, can soften a rash relationship of manipulation and abuse—the notion that romance is redeeming in itself. Today, this view continues by way of commercial narratives that promise (and, of course, fail) to fulfill our desires for love and belonging and personal identity, if only we spend enough. An organization like Scientology can pick up precisely where such promises disappoint.

Scientology’s special manipulations of language seduced Hall and kept her bound to the church. Although, at first, she was skeptical of the “Standard Tech”—Hubbard’s official writings—it eventually came to shape her life. When Faunt’s friend explained the “thetan,” or spirit, as a being that is “aware of being aware,” Hall was intrigued: “I liked that very much. It tied in with my meditating efforts.” Later, Faunt introduced her to the concept of the “overt,” a transgression against the ethics of the church. “Not an adjective. A noun,” he explained. “This kind of clarity of language, common to Scientologists, I found very appealing,” Hall writes. Studying words during the church’s “auditing” process made language a “teeming garden of possibilities,” but she also saw the problem:

Language connects people, of course, binding us into a uniquely shared world, while also serving as a barrier, separating us from others. It would take a long time to realize how Scientology’s vocabulary, its nomenclature, abetted such binding, and how purposeful Hubbard had been in creating it. I knew then only that the orderly aspects of the religion were deeply appealing, helping me sort through a terrible, consuming confusion.

Reflecting on the way that Scientology’s language circumscribed her thought, Hall invokes 1984, but it’s more as though Orwell’s Newspeak had conceived a ghastly child with a Walmart employee handbook. Language is the vehicle for both the church’s tyrannical mode and its corporate flourishes. Consider this scene where Faunt, now Hall’s husband, drags her before an “Ethics Officer” named Marty to unspool their conjugal woes. Hall invests it with the same droll energy that makes the sci-fi dystopia of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We feel hilariously familiar to anyone who has ever endured a big-box retail training session, with all its bizarre jargon:

Marty looked grave. Jamie [Faunt] leaned forward. “It’s a classic case of Potential Trouble Source. She’s connected to people opposed to Scientology, she’s rollercoastering; she gets better, she gets worse. She’s got a Suppressive Person on her lines. Probably two!”

The phrase “on her lines” made me think of a cobweb, a spider crouched in wait. But it had to do with “comm lines”: those with whom I communicated.

Marty moved his concerned eyes to meet mine. “Who’s invalidating you? Who doesn’t want you to thrive?”

“Her parents!” Jamie said.

In the end, Hall’s focus on this “cobweb” of intimate entanglement is what makes Flunk. Start. compelling—and different from other, more extraordinary accounts of abuse in Scientology’s upper echelons. Lawrence Wright’s Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief, for example, concentrates on the experiences of celebrities like the filmmaker Paul Haggis, who slowly became aware of the church’s sensational cruelties of forced labor and “disconnection” from family, and former church executives like Mike Rinder, whom Miscavige and his deputies routinely beat up when things went awry.

By contrast, Flunk. Start. is most revealing in its depiction of Scientology as just one of many expressions that the American search for selfhood can manifest. Sharing her experience with others convinces Hall that hers is “simply a version of a journey taken by most of us at some point in this life.” It’s not so different, she writes, from other sources of shame—“the decade in the terrible marriage, the years lost to Oxycontin, the time in an ashram agreeing to and participating in sexual coercion”—and “we wouldn’t be who we are without having had those years and learned those lessons in our particular underworlds.” Part of what makes Hall a sympathetic narrator is that she’s divided, ambivalent about the church’s teachings, always aching for an excuse to exit. She’s like a hostage holding herself at gunpoint.

Finally, she has to figure out her own escape. Miscavige’s corporate gloss provided the alibi she needed. A middle-class kid in a middle-class cult, Hall had middle-class resources at her disposal: a family to stay with, an inheritance to collect, the means to go to graduate school (rather than going through the “deprogramming” that others often require). She got an MFA from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The passion for language that the church inspired has found a deeper channel as she became a novelist and professor of writing. Her debut novel, Catching Heaven (2000), concerns two sisters who face their own transformative conflicts and emerge the wiser. Literature serves as the symbolic inverse of a system like Scientology, rewarding close reading with a multiplicity of understandings—rather than exactly one. Having “flunked” a period of life, Hall got a chance to “start” anew. Of course, she didn’t invent this cycle of unhappiness, self-indulgence, and redemption. More than anything, she’s a product of it.

Michael Friedrich is a writer, editor, and researcher based in Brooklyn, covering the intersection of art and social justice.

https://www.thenation.com/article/the-power-of-the-word/

https://www.thenation.com/article/the-power-of-the-word/

No comments:

Post a Comment