How a group of Christian outcasts banded together to expose alleged sexual assault and manipulation that was happening within its ranks

ANDREA MARKS

Rolling Stone

AUGUST 3, 2023

IN 1991, WHEN Chele Roland was a college student, regular customers at the diner where she worked persuaded her to come to the Los Angeles International Church of Christ, a protestant evangelical church with a handful of locations in the greater L.A. area. “I was always a seeker and a do-gooder,” she says. “They made me feel like God himself had sought me out, and I was going to help them change the world.” The same day she first attended a service with them at the Wiltern Theater, she learned her father had died unexpectedly. When the woman from the diner called her that evening to follow up, she told her what had happened. The woman assured her God had brought her to the church for a reason. Looking back, she feels like the ICOC exploited her vulnerability to draw her into a controlling group that dominated the next 17 years of her life.

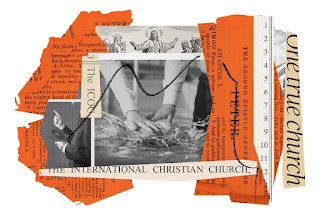

According to two lawsuits filed July 13 in L.A. County Court, the International Churches of Christ (ICOC) is not a church, but a “cult,” a high-control group where leaders allegedly take advantage of the members. The crux of the claims in the lawsuits is the allegation that leaders at the ICOC, as well as some related entities, have for decades covered up sexual abuse and rape to protect themselves from scandal. In one lawsuit, four women claimed they were sexually abused as children in the 1990s by the same then-church member, who is now serving a 40-year sentence for child rape, and that when their parents reported the abuse, church leadership actively discouraged them from going to the police; in the other, a woman claimed she was sexually abused by a children’s ministry teacher, also in the 1990s, and that after her parents reported the abuse, leadership failed to remove him from his role in the ministry, known as Kid’s Kingdom. Beyond the abuse claims, the plaintiffs allege that a hierarchy of church elders known as “disciplers” monitored and controlled “every aspect of every member’s life,” imposed “recruiting quotas” on members to increase the group’s ranks, demanded large portions of their income as part of a “highly profitable pyramid scheme,” and subjected some LGBTQ members to “conversion therapy.”

The allegations in the L.A. lawsuits, which refer to alleged incidents in the 1990s and 2000s, first appeared among a set of six federal lawsuits filed around the start of 2023 in California’s Central District. In July, the plaintiffs withdrew the federal suits. Their attorney says they plan to temporarily shelve federal RICO claims related to the alleged “pyramid scheme” and to refile all of them — with an emphasis on the abuse claims — in state courts. “Our thinking was, let’s focus on what’s important here, which are the claims relating to the sexual abuse of these survivors,” says Bobby Samini, attorney for the plaintiffs.

After Rolling Stone covered the filing of the first federal lawsuit at the end of December, more than a dozen former ICOC members reached out, sharing allegations similar to those enumerated in the legal filings, including claims that they’d endured sexual abuse, controlling behaviors, and conversion therapy as church members. These defectors, and the thousands more organizing on social media, see themselves as part of a wave destined to finally bring down the ICOC. Samini, the plaintiffs’ attorney, believes the child abuse allegations are a good starting point. “This type of abuse was happening in the ICC and the ICOC without any obstacle,” Samini says. “There was nobody in the organization that had the power or the ability to get in front of this and to stop it. Filing these cases was the only mechanism by which to bring it to the attention of the public and to turn the microscope on these organizations, so that the conduct will stop.”

ICOC FOUNDER THOMAS “KIP” McKean, born in 1954, was baptized through a campus ministry program at the University of Florida. In 1977, according to a letter from an archived page on McKean’s own website, he was fired from a Protestant church in Illinois for teaching doctrines “not in accordance with the Bible,” including denying people baptism until they were deemed ready, holding that people must suffer for the salvation of others, and the idea that Christians should confess their every sin to a prayer partner, “no matter how personal, how intimate, or how destructive that might be.”

In 1979, he founded the ICOC in Boston. Thanks in part to its practice of recruiting members via campus ministries, it reportedly became one of the fastest-growing Christian groups of its time. Today, plaintiffs say the ICOC has more than 120,000 members across 144 nations. Originally called the Boston Movement, the church took theological cues from the conventional Churches of Christ, a loosely associated group of conservative Protestant congregations, including relying on scripture as the sole basis for its teachings, and holding that baptism by full immersion in water is necessary for salvation. The ICOC had its own practices, too, namely the system of “discipling,” where church elders offered members spiritual and personal guidance, and to whom members were directed to confess all their sins. Further, the ICOC, as designed by McKean, plaintiffs said, held that its members were the only Christians chosen by God for salvation in heaven.

It didn’t take long for the group to catch negative media attention. In the 1990s, several national outlets, from 20/20 to Seventeen, reported on allegations that the ICOC was a “cult” that took advantage of its members. By 1992, according to an article that ran in Time, despite its growth, roughly half the number of people who had joined since its founding had defected, claiming the church demanded authoritarian control over members’ lives. In 1994, the mainline Churches of Christ severed ties with the group. According to a 2000 U.S. News & World Report article, by that point, at least 39 colleges and universities had banned the ICOC, including Harvard and Georgia State, for harassing students or violating door-to-door recruitment policies.

In the early 2000s, McKean split from the group amid criticism of the allegedly “extreme” and “abusive” discipleship leadership structure. In 2006, he started another group, the International Christian Church (ICC), and has since urged Christians everywhere to join his new, more “zealous” movement.

Both McKean and the ICC are being sued in the two L.A. lawsuits, alongside the ICOC. McKean declined to comment on the allegations in the L.A. lawsuits and on the allegations that he founded a church with what plaintiffs describe as an “authoritarian” leadership structure. An attorney for the ICC did not respond to a request for comment on either the federal or the state lawsuits. Before the plaintiffs requested the dismissal of the federal suits, McKean and ICC had both filed motions to have the federal claims against them dismissed.

Attorney Byron McLain, who filed motions to dismiss on behalf of the ICOC in the federal suits before the plaintiffs withdrew them, says the ICOC is not a single entity anymore. “ICOC Inc. is a dissolved corporation, which no longer has any employees, directors or officers,” he says. His motion argued that because of this, the defendant had been improperly served. Two current members, who spoke with Rolling Stone anonymously, also pushed back against the ICOC being viewed as a whole. They say that while ICOC churches share the same doctrine and belief system, leadership varies greatly among them. “Each ICOC church is operated very differently from the next,” says one teen ministry leader. “You won’t really find the same policies and procedures from church to church.”

Another longtime member says there is a group of leaders making decisions for the ICOC regarding “planning” and “vision,” but no “head honcho” since McKean. He thinks the success of individual churches depends on the behavior of leaders at each one, but he reached out to Rolling Stone because he’s recently had misgivings about the church. “When you start telling people, ‘Here’s how you’re gonna spend your money,’ and you start holding people’s sin and secrets against them, and you start saying, ‘We’re this one church, and we’re the only ones that have it right,’ all those things 100 percent sound like a cult,” he says. “And that’s hard to come to grips with, because that’s not the reason I became a member of this church.”

TYLER CABLE-MONTECLARO, 23, who is not a plaintiff in any of the lawsuits, used to be what’s known in the ICOC as a Kingdom Kid — someone who was raised in the church. Growing up during the aughts in the South Bay Church, part of the L.A. Church of Christ, she was a good kid, even serving on a worship team to lead songs during services. From around age eight, she claims church members told her how to behave as a girl, and that included not “distracting” older men with how she dressed. “I have a little bit of a curvier figure, and when my hips started to develop, people would tell me I can’t wear shorts anymore,” she says. One time, she says, a member of church leadership came to her house and threw all of her shorts in the trash. By the time she was a teen, she would pack an extra outfit for church, in case someone didn’t like what she wore. While onstage with the worship team, she felt “on display,” she says. After services, older church members sometimes approached her. “I would have grown men coming up to me, telling me that they weren’t able to focus [during] the worship, because my outfit was too distracting,” she says. “It got so bad that when I looked in the mirror I just saw a body, something to look at for sex. That’s a confusing place to be, especially as a young person.”

At the same time, Cable-Monteclaro alleges, as she was growing up, she was trying to get church elders and leaders to realize that a family member, who was also part of the church, had been sexually abusing her from a young age. A 2016 police report she shared with Rolling Stone shows she accused that individual of abusing her for nine years, starting in 2007, when she was seven. She claims she tried to tell church members about it before then on multiple occasions, but she didn’t know who to trust, so she only hinted at problems, or mimicked the behaviors of abused children that she’d learned watching CSI — including biting her nails, sitting on her hands, and curling up in the fetal position. “Unfortunately, nobody understood what I was saying,” she says.

It was not until her junior year of high school that she told a teen leader at her church, who helped her report the alleged abuse to the police. That teen leader, who has since left the South Bay Church, confirmed Cable-Monteclaro’s account to Rolling Stone. “She couldn’t even say it out loud. She wrote it in a notebook,” she says. “I called CPS right away.” She believes Cable-Monteclaro’s allegations were credible.

Cable-Monteclaro says that because her relative led a children’s choir, she tried to bring attention to the abuse allegations after she went to the police. Church leaders told her they weren’t going to say anything because, she says, they feared litigation. That individual didn’t leave the church, she says, until she got a no-contact restraining order against them. The former teen leader says it’s true Cable-Monteclaro’s relative did not stop attending the church until after the restraining order, and that a church-wide announcement was never made, but she adds that the individual was no longer allowed to lead the choir after the police report was filed. Cable-Monteclaro’s relative was not arrested or charged with a crime related to the abuse allegations. The individual and an attorney representing them in an unrelated civil action did not respond to emails detailing Cable-Monteclaro’s allegations of abuse.

In June, the former leaders of Cable-Monteclaro’s church, Steve Gansert-Morici and Jacqueline Brown-Morici, were named as defendants in one of the since-dismissed federal lawsuits against the ICOC. In July, the claims against them — including failure to report suspected child abuse at a different ICOC church — were refiled in a state-level suit. The allegations refer to an incident, unrelated to Cable-Monteclaro, in the late 1990s, when the married couple allegedly failed to report the sexual abuse of a three-year-old girl to authorities, and, according to the complaints, “implored other ICOC members not to report it.” Shortly before the dismissal of the federal cases, Byron McLain, an attorney for the Moricis, offered a statement to Rolling Stone calling the federal claims against the Moricis “baseless and unfounded.” He said, “Steve Gansert-Morici and Jaqueline Brown-Morici support all efforts to hold accountable those responsible for such acts. But accusations of child abuse and misconduct against those who are not responsible for the abuse is reputationally and financially damaging.” He had filed a motion to dismiss the federal claims, stating the allegations “fail to meet the legal standard of pleadings at this stage of the proceeding and are barred by the statute of limitations.” He has declined to offer further comment on the state lawsuit, and it is unclear if he is representing them in the lawsuit.

As for Cable-Monteclaro, McLain stated, “The alleged abuse of Tyler Cable occurred in her home and not at the church. Nevertheless, the church helped Tyler Cable obtain a restraining order against her alleged abuser.” He added, “Steve Morici was at the police station with Tyler Cable and answered any questions the Special Victims Unit and DCFS had.” The attorney declined to comment about Cable-Monteclaro’s relative’s role leading the choir. Cable-Monteclaro says Steve Morici did come to the police station the night she was there, but she believes church leaders should be doing more to identify and prevent abuse of children and to keep alleged abusers from maintaining access to kids. “Maybe instead of having countless talks to young girls about purity and what not to wear, maybe we can talk about consent,” she says. “When grown men are confessing that they have feelings for children because of what they’re wearing … why not respond? You can clearly see where the issue is and how they as a church are perpetuating it. But they refuse to take responsibility.” She left the church in 2020.

IN SOME CASES, former members say, leaders and elders in the church took advantage of their power over other members. Mike Hammer, who is not a plaintiff in the lawsuits, says he was “groomed” and abused starting in 1985, under the guise of campus ministry, by an ICOC leader at the University of Alabama – Huntsville. A student when he discovered the ministry, he was enthusiastic about joining full time after he graduated. Private training with a campus minister slowly progressed from meetings at church to invitations to the man’s home, to “let’s go to the bedroom and let’s talk,” says Hammer, 60. There, Hammer says, the campus minister told him he and other church leaders used to give each other backrubs, so they started doing that, too.

It was during a conversation about sex that Hammer claims the campus minister first abused him. Hammer was taught to confess his sins to the minister, including premarital sexual activities. In early 1986, while exchanging backrubs, Hammer says he told the minister he had prematurely ejaculated while kissing his fiancée. “That’s when he touched me for the first time,” he says. Hammer was 22, of age to legally consent, but he believes his minister, in a position of leadership, took advantage of the situation. “This was abuse of power,” he says.

Over time, what began as fondling turned into encounters that were more sexual in nature, including oral sex, Hammer says. After nearly two years, he divulged the incidents to a group of people in the church as part of their Bible study series, where they were prompted to confess their sins to the group. It was treated as an affair, he says. The campus minister left because of the “affair,” and Hammer says he was essentially told to “hush up and move on.” Hammer, who had by this point moved to Boston, stopped pursuing ministry work but continued going to church with the ICOC. The campus minister did not respond to a request for comment.

Michael Van Auken, a preacher with the Boston ICOC, acknowledged in a statement to Rolling Stone that Hammer had “a sexual encounter with a staff member” in the late 1980s. “Once Mr. Hammer made the situation known, that staff member was fired for adulterous behavior,” Van Auken said. He added, “The Boston Church of Christ stands firmly against the social, emotional, or physical abuse of anyone at any time. It is sinful, ungodly and will not be tolerated or protected. Our hearts break to hear of the possibility of anyone suffering abuse. The Boston Church staff and its elders are united in their determination to protect our members and staff in this regard.”

Hammer eventually quit the ICOC in 2009. His marriage fell apart, and he joined a support group to help him process the alleged abuse. Hammer has since remarried, but he can’t attend church anymore. “My wife and I go visit, but I have triggers,” he says. He sees his alleged abuser in church leaders everywhere. “It’s the personality type,” he says.

AFTER ROLAND’S FIRST VISIT to the ICOC, she says, church members hustled her through a series of Bible studies before she was baptized and thrust into a new life as a “disciple.” Roland claims she was monitored by senior members and chastised when she stepped out of line. Church members told her who to date and marry, how to dress, and how to bring in new members — which she says was a crucial element of her role as a disciple. She says she quickly became totally isolated from the outside world, convinced that the ICOC was right about saving her from hell.

She threw herself into the lifestyle, attending services multiple times a week, and working to meet “recruitment quotas.” She worked full time as an “intern” in the church, plus an extra part-time job on the side. Sometimes, she went days without sleeping. She claimed in a since-dismissed federal lawsuit that she tithed 20 percent of her income to the church the entire 17 years she was a member.

When Roland first started attending church with the ICOC, members taught her to be very reserved. She says she was chided for wearing a sports bra on a jog, and she was told women were required to wear shorts and T-shirts to the beach instead of bikinis. Once she was a member of the church and married to someone the leadership had chosen for her, however, she says sex talk was on the table, and not in a way that made her any more comfortable. Her and her then-husband’s discipler would grill her about her sex life, according to a since-dismissed lawsuit, where she was identified at Jane Roe 1. After her honeymoon, he asked her at a dinner with several other church leaders whether she’d had “an orgasm” with her new husband. She blurted out “No,” and ran to the bathroom and cried, the complaint alleged. The discipler later lectured her on having a “healthy sex life” in order to be a leader in the marriage ministry. He instructed her to practice and report to him when she was having orgasms.

“They have this weird under-sexualized culture in some ways, but over-sexualized in other ways,” Roland says. “People are making allegations of rape and abuse and being told they can’t go to the police about it. But I can’t wear a sports bra.” The lawsuits allege that church leaders repeatedly discouraged accusers from reporting abuse allegations to police to protect the church.

It wasn’t until she says she experienced serious health problems that she knew she had to leave. One day in 2008, she says, she drove herself to the hospital. “I was having heart complications,” Roland says. “The doctor came in and said, ‘If you don’t stop whatever it is you’re doing, and start sleeping and taking care of yourself, I give you about two years.’” Roland, then 38, decided she was done with the International Churches of Christ. “I was like, I’m out,” she says. “I’m out. I don’t care what I gotta do.”

LIFE WITH THE ICOC never started out bad — typically, it was quite the opposite. Former members who spoke with Rolling Stone say “love bombing” was part of the recruitment approach. Nicole, now a licensed clinical social worker, had just broken up with their middle-school girlfriend, when one of their teachers introduced them to the ICOC in Orlando, Florida, in the 1990s. They instantly found comfort for their heartbreak. “I felt like the most important person, because they wanted to spend time with me, they wanted to get to know me, they wanted to take me out for ice cream,” Nicole says. “And then, eventually, they wanted to start studying the Bible with me.” (Nicole asked to be identified by their first name only, to make it harder for ICOC members to locate them. They are not a plaintiff in the lawsuits.)

Nicole, 42, was out and open with their sexuality, even as a middle-schooler, but once they were committed to the ICOC, they say they were subjected to conversion therapy, which the American Psychological Association says can lead to depression, low self-esteem, and suicide. “After I made all these friends … they’re like, ‘You can’t be with God and be gay.’” The church members called gay people “same-sex attracted,” they say, and while the church acknowledged a person can’t help those feelings of attraction, you weren’t supposed to act on them. “Effectively, you have to either be celibate, or date heterosexually,” Nicole says. Beyond that, they claim, leaders pressured them to present themself as more feminine, by painting their nails, wearing dresses, and putting on makeup. “It was just constant censoring of my inherent gender, but also trying to get me to be something else that I wasn’t,” they say. “It sends this message that you’re not good enough as you are.” The Orlando ICOC did not respond to a request for comment.

By the time Nicole was in college, they had switched ICOC churches within Florida to be closer to their campus, and they were experiencing serious depression. It was around that time that they began self-injuring. They say they began seeing a church-sanctioned therapist, who told them they couldn’t play rugby anymore, or drive a truck, because those things would cause them to “struggle” — which multiple sources say is the church’s preferred term for feeling inappropriate sexual urges.

Soon, Nicole felt chronically suicidal. “I just remember one day, l was driving, and I had this thought of, ‘If I don’t leave the church, God, I’m going to kill myself,’” they say. They left, a decade after they’d joined. They lost their entire social circle in the process. “It’s like ripping every single structure that you have, or any idea that you had about how life is, and it’s just gone,” they say.

In recent years, multiple locations of the ICOC have hosted events with an LGBTQ ministry called Strength in Weakness, led by a man named Guy Hammond, who describes himself as a “homosexually attracted Christian” on his website. Megan Poirier, 24, a lesbian ex-ICOC member who was raised in ICOC churches in Boston and for a few years in Texas, first saw Hammond speak at a Friday night teen devotional outside of Boston almost a decade ago. She claims Hammond called himself “ex-gay,” and that some church members referred to his program as the “ex-gay ministry,” although never officially.

“I think that they have been trying to stay away from terms like that because it’s very closely associated with conversion therapy, and they don’t want to give people that impression, but it’s sort of the same thing,” she says. Hammond did not respond to a request for comment. The Strength in Weakness website denies using conversion therapy. “Strength in Weakness Inc. does not support conversion therapy and does not use conversion therapy in any manner,” it states. “It is not the goal of Strength in Weakness Ministries or Strength in Weakness Inc. to have any person change or alter their sexual attraction or identity.”

FOR DECADES, EX-ICOC and ex-ICC members have connected on internet forums, but in recent years, there has been a renewed rumbling among defectors in Facebook groups. Finding a more mainstream space to share their experiences with the church seemed to galvanize a new push for accountability. Roland describes it like the ICOC’s own iteration of the #MeToo movement. In 2021, she also began co-hosting a podcast about surviving cults and started getting contacted directly by former members of the ICOC. Many of the people she spoke with, she says, had stories of alleged sexual abuse within the church.

Roland connected with attorney Bobby Samini, who filed the initial spate of six federal complaints in California as well as the two complaints to be filed so far in L.A. County. Once word of the legal action began circulating among Facebook group members, more people joined the fight.

Anthony “Andy” Stowers Forest is one such plaintiff, who alleged in a since-dismissed federal lawsuit that he was sexually abused from a young age by multiple leaders while attending ICOC churches in Florida and Georgia. He’d posted earlier in the year about his experience of abuse in the discussion of an ex-member group. One day in late 2022, he got a DM from another ex-member telling him Roland had hired a lawyer for people who’d been abused as children in the church. “I contacted her immediately,” he says. After hearing some of his allegations, she asked him to fly out and meet with Samini, who agreed to represent him.

Roland estimates that she and Samini have fielded more than 1,200 calls from former members since she first got involved. They are planning to file some cases in Boston in the coming months, another major hub of the ICOC. She continues to urge former members to come forward. She and the other people who spoke with Rolling Stone hope this wave of legal action could be enough to finally stop the church’s alleged cycle of recruitment, control, and abuse.

As a former teen leader, Cable-Monteclaro worries about the girls she used to mentor who are still in the ICOC. She’s thought about reaching out to some of them, but she says her conversations with current members haven’t gone well in the past. “If someone who is not a part of the church reaches out, there’s this level of, ‘They don’t know what they’re talking about, they don’t know what they’re saying, because Satan has clouded their judgment,’” she says. “That’s the hardest part of trying to reach overzealous Christians. It doesn’t matter what you do or say to them, it makes them stronger, because they believe if you attack them, they’re being persecuted, and that makes their faith stronger.

https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/icoc-members-alleged-abuse-cult-behavior-1234798928/

ANDREA MARKS

Rolling Stone

AUGUST 3, 2023

IN 1991, WHEN Chele Roland was a college student, regular customers at the diner where she worked persuaded her to come to the Los Angeles International Church of Christ, a protestant evangelical church with a handful of locations in the greater L.A. area. “I was always a seeker and a do-gooder,” she says. “They made me feel like God himself had sought me out, and I was going to help them change the world.” The same day she first attended a service with them at the Wiltern Theater, she learned her father had died unexpectedly. When the woman from the diner called her that evening to follow up, she told her what had happened. The woman assured her God had brought her to the church for a reason. Looking back, she feels like the ICOC exploited her vulnerability to draw her into a controlling group that dominated the next 17 years of her life.

According to two lawsuits filed July 13 in L.A. County Court, the International Churches of Christ (ICOC) is not a church, but a “cult,” a high-control group where leaders allegedly take advantage of the members. The crux of the claims in the lawsuits is the allegation that leaders at the ICOC, as well as some related entities, have for decades covered up sexual abuse and rape to protect themselves from scandal. In one lawsuit, four women claimed they were sexually abused as children in the 1990s by the same then-church member, who is now serving a 40-year sentence for child rape, and that when their parents reported the abuse, church leadership actively discouraged them from going to the police; in the other, a woman claimed she was sexually abused by a children’s ministry teacher, also in the 1990s, and that after her parents reported the abuse, leadership failed to remove him from his role in the ministry, known as Kid’s Kingdom. Beyond the abuse claims, the plaintiffs allege that a hierarchy of church elders known as “disciplers” monitored and controlled “every aspect of every member’s life,” imposed “recruiting quotas” on members to increase the group’s ranks, demanded large portions of their income as part of a “highly profitable pyramid scheme,” and subjected some LGBTQ members to “conversion therapy.”

The allegations in the L.A. lawsuits, which refer to alleged incidents in the 1990s and 2000s, first appeared among a set of six federal lawsuits filed around the start of 2023 in California’s Central District. In July, the plaintiffs withdrew the federal suits. Their attorney says they plan to temporarily shelve federal RICO claims related to the alleged “pyramid scheme” and to refile all of them — with an emphasis on the abuse claims — in state courts. “Our thinking was, let’s focus on what’s important here, which are the claims relating to the sexual abuse of these survivors,” says Bobby Samini, attorney for the plaintiffs.

After Rolling Stone covered the filing of the first federal lawsuit at the end of December, more than a dozen former ICOC members reached out, sharing allegations similar to those enumerated in the legal filings, including claims that they’d endured sexual abuse, controlling behaviors, and conversion therapy as church members. These defectors, and the thousands more organizing on social media, see themselves as part of a wave destined to finally bring down the ICOC. Samini, the plaintiffs’ attorney, believes the child abuse allegations are a good starting point. “This type of abuse was happening in the ICC and the ICOC without any obstacle,” Samini says. “There was nobody in the organization that had the power or the ability to get in front of this and to stop it. Filing these cases was the only mechanism by which to bring it to the attention of the public and to turn the microscope on these organizations, so that the conduct will stop.”

ICOC FOUNDER THOMAS “KIP” McKean, born in 1954, was baptized through a campus ministry program at the University of Florida. In 1977, according to a letter from an archived page on McKean’s own website, he was fired from a Protestant church in Illinois for teaching doctrines “not in accordance with the Bible,” including denying people baptism until they were deemed ready, holding that people must suffer for the salvation of others, and the idea that Christians should confess their every sin to a prayer partner, “no matter how personal, how intimate, or how destructive that might be.”

In 1979, he founded the ICOC in Boston. Thanks in part to its practice of recruiting members via campus ministries, it reportedly became one of the fastest-growing Christian groups of its time. Today, plaintiffs say the ICOC has more than 120,000 members across 144 nations. Originally called the Boston Movement, the church took theological cues from the conventional Churches of Christ, a loosely associated group of conservative Protestant congregations, including relying on scripture as the sole basis for its teachings, and holding that baptism by full immersion in water is necessary for salvation. The ICOC had its own practices, too, namely the system of “discipling,” where church elders offered members spiritual and personal guidance, and to whom members were directed to confess all their sins. Further, the ICOC, as designed by McKean, plaintiffs said, held that its members were the only Christians chosen by God for salvation in heaven.

It didn’t take long for the group to catch negative media attention. In the 1990s, several national outlets, from 20/20 to Seventeen, reported on allegations that the ICOC was a “cult” that took advantage of its members. By 1992, according to an article that ran in Time, despite its growth, roughly half the number of people who had joined since its founding had defected, claiming the church demanded authoritarian control over members’ lives. In 1994, the mainline Churches of Christ severed ties with the group. According to a 2000 U.S. News & World Report article, by that point, at least 39 colleges and universities had banned the ICOC, including Harvard and Georgia State, for harassing students or violating door-to-door recruitment policies.

In the early 2000s, McKean split from the group amid criticism of the allegedly “extreme” and “abusive” discipleship leadership structure. In 2006, he started another group, the International Christian Church (ICC), and has since urged Christians everywhere to join his new, more “zealous” movement.

Both McKean and the ICC are being sued in the two L.A. lawsuits, alongside the ICOC. McKean declined to comment on the allegations in the L.A. lawsuits and on the allegations that he founded a church with what plaintiffs describe as an “authoritarian” leadership structure. An attorney for the ICC did not respond to a request for comment on either the federal or the state lawsuits. Before the plaintiffs requested the dismissal of the federal suits, McKean and ICC had both filed motions to have the federal claims against them dismissed.

Attorney Byron McLain, who filed motions to dismiss on behalf of the ICOC in the federal suits before the plaintiffs withdrew them, says the ICOC is not a single entity anymore. “ICOC Inc. is a dissolved corporation, which no longer has any employees, directors or officers,” he says. His motion argued that because of this, the defendant had been improperly served. Two current members, who spoke with Rolling Stone anonymously, also pushed back against the ICOC being viewed as a whole. They say that while ICOC churches share the same doctrine and belief system, leadership varies greatly among them. “Each ICOC church is operated very differently from the next,” says one teen ministry leader. “You won’t really find the same policies and procedures from church to church.”

Another longtime member says there is a group of leaders making decisions for the ICOC regarding “planning” and “vision,” but no “head honcho” since McKean. He thinks the success of individual churches depends on the behavior of leaders at each one, but he reached out to Rolling Stone because he’s recently had misgivings about the church. “When you start telling people, ‘Here’s how you’re gonna spend your money,’ and you start holding people’s sin and secrets against them, and you start saying, ‘We’re this one church, and we’re the only ones that have it right,’ all those things 100 percent sound like a cult,” he says. “And that’s hard to come to grips with, because that’s not the reason I became a member of this church.”

TYLER CABLE-MONTECLARO, 23, who is not a plaintiff in any of the lawsuits, used to be what’s known in the ICOC as a Kingdom Kid — someone who was raised in the church. Growing up during the aughts in the South Bay Church, part of the L.A. Church of Christ, she was a good kid, even serving on a worship team to lead songs during services. From around age eight, she claims church members told her how to behave as a girl, and that included not “distracting” older men with how she dressed. “I have a little bit of a curvier figure, and when my hips started to develop, people would tell me I can’t wear shorts anymore,” she says. One time, she says, a member of church leadership came to her house and threw all of her shorts in the trash. By the time she was a teen, she would pack an extra outfit for church, in case someone didn’t like what she wore. While onstage with the worship team, she felt “on display,” she says. After services, older church members sometimes approached her. “I would have grown men coming up to me, telling me that they weren’t able to focus [during] the worship, because my outfit was too distracting,” she says. “It got so bad that when I looked in the mirror I just saw a body, something to look at for sex. That’s a confusing place to be, especially as a young person.”

At the same time, Cable-Monteclaro alleges, as she was growing up, she was trying to get church elders and leaders to realize that a family member, who was also part of the church, had been sexually abusing her from a young age. A 2016 police report she shared with Rolling Stone shows she accused that individual of abusing her for nine years, starting in 2007, when she was seven. She claims she tried to tell church members about it before then on multiple occasions, but she didn’t know who to trust, so she only hinted at problems, or mimicked the behaviors of abused children that she’d learned watching CSI — including biting her nails, sitting on her hands, and curling up in the fetal position. “Unfortunately, nobody understood what I was saying,” she says.

It was not until her junior year of high school that she told a teen leader at her church, who helped her report the alleged abuse to the police. That teen leader, who has since left the South Bay Church, confirmed Cable-Monteclaro’s account to Rolling Stone. “She couldn’t even say it out loud. She wrote it in a notebook,” she says. “I called CPS right away.” She believes Cable-Monteclaro’s allegations were credible.

Cable-Monteclaro says that because her relative led a children’s choir, she tried to bring attention to the abuse allegations after she went to the police. Church leaders told her they weren’t going to say anything because, she says, they feared litigation. That individual didn’t leave the church, she says, until she got a no-contact restraining order against them. The former teen leader says it’s true Cable-Monteclaro’s relative did not stop attending the church until after the restraining order, and that a church-wide announcement was never made, but she adds that the individual was no longer allowed to lead the choir after the police report was filed. Cable-Monteclaro’s relative was not arrested or charged with a crime related to the abuse allegations. The individual and an attorney representing them in an unrelated civil action did not respond to emails detailing Cable-Monteclaro’s allegations of abuse.

In June, the former leaders of Cable-Monteclaro’s church, Steve Gansert-Morici and Jacqueline Brown-Morici, were named as defendants in one of the since-dismissed federal lawsuits against the ICOC. In July, the claims against them — including failure to report suspected child abuse at a different ICOC church — were refiled in a state-level suit. The allegations refer to an incident, unrelated to Cable-Monteclaro, in the late 1990s, when the married couple allegedly failed to report the sexual abuse of a three-year-old girl to authorities, and, according to the complaints, “implored other ICOC members not to report it.” Shortly before the dismissal of the federal cases, Byron McLain, an attorney for the Moricis, offered a statement to Rolling Stone calling the federal claims against the Moricis “baseless and unfounded.” He said, “Steve Gansert-Morici and Jaqueline Brown-Morici support all efforts to hold accountable those responsible for such acts. But accusations of child abuse and misconduct against those who are not responsible for the abuse is reputationally and financially damaging.” He had filed a motion to dismiss the federal claims, stating the allegations “fail to meet the legal standard of pleadings at this stage of the proceeding and are barred by the statute of limitations.” He has declined to offer further comment on the state lawsuit, and it is unclear if he is representing them in the lawsuit.

As for Cable-Monteclaro, McLain stated, “The alleged abuse of Tyler Cable occurred in her home and not at the church. Nevertheless, the church helped Tyler Cable obtain a restraining order against her alleged abuser.” He added, “Steve Morici was at the police station with Tyler Cable and answered any questions the Special Victims Unit and DCFS had.” The attorney declined to comment about Cable-Monteclaro’s relative’s role leading the choir. Cable-Monteclaro says Steve Morici did come to the police station the night she was there, but she believes church leaders should be doing more to identify and prevent abuse of children and to keep alleged abusers from maintaining access to kids. “Maybe instead of having countless talks to young girls about purity and what not to wear, maybe we can talk about consent,” she says. “When grown men are confessing that they have feelings for children because of what they’re wearing … why not respond? You can clearly see where the issue is and how they as a church are perpetuating it. But they refuse to take responsibility.” She left the church in 2020.

IN SOME CASES, former members say, leaders and elders in the church took advantage of their power over other members. Mike Hammer, who is not a plaintiff in the lawsuits, says he was “groomed” and abused starting in 1985, under the guise of campus ministry, by an ICOC leader at the University of Alabama – Huntsville. A student when he discovered the ministry, he was enthusiastic about joining full time after he graduated. Private training with a campus minister slowly progressed from meetings at church to invitations to the man’s home, to “let’s go to the bedroom and let’s talk,” says Hammer, 60. There, Hammer says, the campus minister told him he and other church leaders used to give each other backrubs, so they started doing that, too.

It was during a conversation about sex that Hammer claims the campus minister first abused him. Hammer was taught to confess his sins to the minister, including premarital sexual activities. In early 1986, while exchanging backrubs, Hammer says he told the minister he had prematurely ejaculated while kissing his fiancée. “That’s when he touched me for the first time,” he says. Hammer was 22, of age to legally consent, but he believes his minister, in a position of leadership, took advantage of the situation. “This was abuse of power,” he says.

Over time, what began as fondling turned into encounters that were more sexual in nature, including oral sex, Hammer says. After nearly two years, he divulged the incidents to a group of people in the church as part of their Bible study series, where they were prompted to confess their sins to the group. It was treated as an affair, he says. The campus minister left because of the “affair,” and Hammer says he was essentially told to “hush up and move on.” Hammer, who had by this point moved to Boston, stopped pursuing ministry work but continued going to church with the ICOC. The campus minister did not respond to a request for comment.

Michael Van Auken, a preacher with the Boston ICOC, acknowledged in a statement to Rolling Stone that Hammer had “a sexual encounter with a staff member” in the late 1980s. “Once Mr. Hammer made the situation known, that staff member was fired for adulterous behavior,” Van Auken said. He added, “The Boston Church of Christ stands firmly against the social, emotional, or physical abuse of anyone at any time. It is sinful, ungodly and will not be tolerated or protected. Our hearts break to hear of the possibility of anyone suffering abuse. The Boston Church staff and its elders are united in their determination to protect our members and staff in this regard.”

Hammer eventually quit the ICOC in 2009. His marriage fell apart, and he joined a support group to help him process the alleged abuse. Hammer has since remarried, but he can’t attend church anymore. “My wife and I go visit, but I have triggers,” he says. He sees his alleged abuser in church leaders everywhere. “It’s the personality type,” he says.

AFTER ROLAND’S FIRST VISIT to the ICOC, she says, church members hustled her through a series of Bible studies before she was baptized and thrust into a new life as a “disciple.” Roland claims she was monitored by senior members and chastised when she stepped out of line. Church members told her who to date and marry, how to dress, and how to bring in new members — which she says was a crucial element of her role as a disciple. She says she quickly became totally isolated from the outside world, convinced that the ICOC was right about saving her from hell.

She threw herself into the lifestyle, attending services multiple times a week, and working to meet “recruitment quotas.” She worked full time as an “intern” in the church, plus an extra part-time job on the side. Sometimes, she went days without sleeping. She claimed in a since-dismissed federal lawsuit that she tithed 20 percent of her income to the church the entire 17 years she was a member.

When Roland first started attending church with the ICOC, members taught her to be very reserved. She says she was chided for wearing a sports bra on a jog, and she was told women were required to wear shorts and T-shirts to the beach instead of bikinis. Once she was a member of the church and married to someone the leadership had chosen for her, however, she says sex talk was on the table, and not in a way that made her any more comfortable. Her and her then-husband’s discipler would grill her about her sex life, according to a since-dismissed lawsuit, where she was identified at Jane Roe 1. After her honeymoon, he asked her at a dinner with several other church leaders whether she’d had “an orgasm” with her new husband. She blurted out “No,” and ran to the bathroom and cried, the complaint alleged. The discipler later lectured her on having a “healthy sex life” in order to be a leader in the marriage ministry. He instructed her to practice and report to him when she was having orgasms.

“They have this weird under-sexualized culture in some ways, but over-sexualized in other ways,” Roland says. “People are making allegations of rape and abuse and being told they can’t go to the police about it. But I can’t wear a sports bra.” The lawsuits allege that church leaders repeatedly discouraged accusers from reporting abuse allegations to police to protect the church.

It wasn’t until she says she experienced serious health problems that she knew she had to leave. One day in 2008, she says, she drove herself to the hospital. “I was having heart complications,” Roland says. “The doctor came in and said, ‘If you don’t stop whatever it is you’re doing, and start sleeping and taking care of yourself, I give you about two years.’” Roland, then 38, decided she was done with the International Churches of Christ. “I was like, I’m out,” she says. “I’m out. I don’t care what I gotta do.”

LIFE WITH THE ICOC never started out bad — typically, it was quite the opposite. Former members who spoke with Rolling Stone say “love bombing” was part of the recruitment approach. Nicole, now a licensed clinical social worker, had just broken up with their middle-school girlfriend, when one of their teachers introduced them to the ICOC in Orlando, Florida, in the 1990s. They instantly found comfort for their heartbreak. “I felt like the most important person, because they wanted to spend time with me, they wanted to get to know me, they wanted to take me out for ice cream,” Nicole says. “And then, eventually, they wanted to start studying the Bible with me.” (Nicole asked to be identified by their first name only, to make it harder for ICOC members to locate them. They are not a plaintiff in the lawsuits.)

Nicole, 42, was out and open with their sexuality, even as a middle-schooler, but once they were committed to the ICOC, they say they were subjected to conversion therapy, which the American Psychological Association says can lead to depression, low self-esteem, and suicide. “After I made all these friends … they’re like, ‘You can’t be with God and be gay.’” The church members called gay people “same-sex attracted,” they say, and while the church acknowledged a person can’t help those feelings of attraction, you weren’t supposed to act on them. “Effectively, you have to either be celibate, or date heterosexually,” Nicole says. Beyond that, they claim, leaders pressured them to present themself as more feminine, by painting their nails, wearing dresses, and putting on makeup. “It was just constant censoring of my inherent gender, but also trying to get me to be something else that I wasn’t,” they say. “It sends this message that you’re not good enough as you are.” The Orlando ICOC did not respond to a request for comment.

By the time Nicole was in college, they had switched ICOC churches within Florida to be closer to their campus, and they were experiencing serious depression. It was around that time that they began self-injuring. They say they began seeing a church-sanctioned therapist, who told them they couldn’t play rugby anymore, or drive a truck, because those things would cause them to “struggle” — which multiple sources say is the church’s preferred term for feeling inappropriate sexual urges.

Soon, Nicole felt chronically suicidal. “I just remember one day, l was driving, and I had this thought of, ‘If I don’t leave the church, God, I’m going to kill myself,’” they say. They left, a decade after they’d joined. They lost their entire social circle in the process. “It’s like ripping every single structure that you have, or any idea that you had about how life is, and it’s just gone,” they say.

In recent years, multiple locations of the ICOC have hosted events with an LGBTQ ministry called Strength in Weakness, led by a man named Guy Hammond, who describes himself as a “homosexually attracted Christian” on his website. Megan Poirier, 24, a lesbian ex-ICOC member who was raised in ICOC churches in Boston and for a few years in Texas, first saw Hammond speak at a Friday night teen devotional outside of Boston almost a decade ago. She claims Hammond called himself “ex-gay,” and that some church members referred to his program as the “ex-gay ministry,” although never officially.

“I think that they have been trying to stay away from terms like that because it’s very closely associated with conversion therapy, and they don’t want to give people that impression, but it’s sort of the same thing,” she says. Hammond did not respond to a request for comment. The Strength in Weakness website denies using conversion therapy. “Strength in Weakness Inc. does not support conversion therapy and does not use conversion therapy in any manner,” it states. “It is not the goal of Strength in Weakness Ministries or Strength in Weakness Inc. to have any person change or alter their sexual attraction or identity.”

FOR DECADES, EX-ICOC and ex-ICC members have connected on internet forums, but in recent years, there has been a renewed rumbling among defectors in Facebook groups. Finding a more mainstream space to share their experiences with the church seemed to galvanize a new push for accountability. Roland describes it like the ICOC’s own iteration of the #MeToo movement. In 2021, she also began co-hosting a podcast about surviving cults and started getting contacted directly by former members of the ICOC. Many of the people she spoke with, she says, had stories of alleged sexual abuse within the church.

Roland connected with attorney Bobby Samini, who filed the initial spate of six federal complaints in California as well as the two complaints to be filed so far in L.A. County. Once word of the legal action began circulating among Facebook group members, more people joined the fight.

Anthony “Andy” Stowers Forest is one such plaintiff, who alleged in a since-dismissed federal lawsuit that he was sexually abused from a young age by multiple leaders while attending ICOC churches in Florida and Georgia. He’d posted earlier in the year about his experience of abuse in the discussion of an ex-member group. One day in late 2022, he got a DM from another ex-member telling him Roland had hired a lawyer for people who’d been abused as children in the church. “I contacted her immediately,” he says. After hearing some of his allegations, she asked him to fly out and meet with Samini, who agreed to represent him.

Roland estimates that she and Samini have fielded more than 1,200 calls from former members since she first got involved. They are planning to file some cases in Boston in the coming months, another major hub of the ICOC. She continues to urge former members to come forward. She and the other people who spoke with Rolling Stone hope this wave of legal action could be enough to finally stop the church’s alleged cycle of recruitment, control, and abuse.

As a former teen leader, Cable-Monteclaro worries about the girls she used to mentor who are still in the ICOC. She’s thought about reaching out to some of them, but she says her conversations with current members haven’t gone well in the past. “If someone who is not a part of the church reaches out, there’s this level of, ‘They don’t know what they’re talking about, they don’t know what they’re saying, because Satan has clouded their judgment,’” she says. “That’s the hardest part of trying to reach overzealous Christians. It doesn’t matter what you do or say to them, it makes them stronger, because they believe if you attack them, they’re being persecuted, and that makes their faith stronger.

https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/icoc-members-alleged-abuse-cult-behavior-1234798928/

No comments:

Post a Comment