Capes. Snakes. Pentagrams. The Process Church of the Final Judgment shocked Toronto the Good — and so did the funding it got from the Liberals

Nate Hendley

TVO

October 07, 2021

On March 1, 1972, MP Wallace Nesbitt, a Progressive Conservative representing Oxford, stood in the House of Commons and demanded to know why the Liberals were funding Satanism in Toronto.

The Liberal government had provided grant money to a religious group “widely reported to promote devil worship with attendant rites and rituals,” said Nesbitt.

The group in question was the Toronto chapter of the Process Church of the Final Judgment, a small sect that was the subject of intense media scrutiny and high-level debate during its brief existence. Church followers (called Processeans) did not engage in devil worship, but the group’s offbeat beliefs and eye-catching outfits made such a misunderstanding all but inevitable.

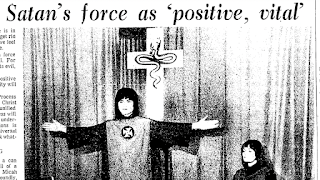

Church leaders wore dark, ankle-length capes and modified crucifixes featuring snake imagery. The Church was partial to the Goat of Mendes emblem, which consists of a goat’s head in a pentagram (“a Satan symbol” according to a Toronto Star profile about the group). Male leaders had long hair and beards, giving them an austere, Rasputin-like appearance.

“Anyone who walks down Yonge Street knows them — bright-eyed young people in long capes of black or blue — wearing strange images of a serpent around their necks,” wrote the Globe on February 5, 1973.

The Process Church was started in 1963 in the United Kingdom by Robert de Grimston and Mary Ann MacLean (the couple later married). Originally a therapeutic movement called Compulsions Analysis, the group transformed into an eclectic religious order with branches in London, Rome, Chicago, New York City, and San Francisco, among other cities. The Toronto chapter was founded in early 1971. That same year, Process Church co-founders de Grimston and MacLean briefly lived in Toronto.

The Process Church adhered to “a complicated theology,” as the Globe and Mail put it. Explained simply, Processeans believed that God consisted of three separate deities: Lucifer, Satan, and Jehovah. The Church extended the Christian concept of loving your enemy to include the devil and espoused an apocalyptic “the end is nigh” philosophy.

In his extensive writings, de Grimston insisted that the Process Church did not worship demons (Did the trinity at the center of the faith represent literal gods, or were they symbols of common personality traits? Members expressed different views). The public found such theological nuances hard to grasp, and the press usually portrayed the order as a bizarre Satanic coven (“Process Church Sees Satan’s Force as ‘Positive, Vital’” stated a May 16, 1973, Toronto Star headline).

Scurrilous rumours connected the Church to terrible people. There were accusations that Process doctrine had inspired Charles Manson (it hadn’t, although the sect interviewed Manson for Process, the Church’s magazine). Serial killer David Berkowitz, who terrorized New York City in the mid-1970s under the alias “the Son of Sam” was said to be a member (a dubious assertion at best).

While these murderous connections were unfounded, the Church might have been guilty of other sins. The book, Love, Sex, Fear, Death: The Inside Story of the Process Church of the Final Judgment chronicled accounts of sexual and psychological abuse in various chapters around the world. Author Timothy Wyllie (a former Process Church member in Toronto and other locales) described the sect as rigid and authoritarian.

The Toronto chapter featured about half a dozen full-time members at first (the order would later claim hundreds of adherents). Church members proselytized on downtown sidewalks and sold books and copies of Process magazine. This slick publication featured interviews with such celebrities as Mick Jagger and articles about esoteric topics. The Toronto branch also operated a drop-in centre and coffee house out of residences at 94 and 99 Gloucester Street. The Church hosted religious services, concerts, and seminars about telepathy that were open to the public.

Initially, things went well: “To our relief [the Toronto branch] quickly became successful. Canadians were generous with us on the street and appeared to enjoy our magazine and started turning up at our Coffee House in droves,” wrote Wyllie.

Prominent followers included funk pioneer George Clinton. Process members got to hang out with the musical genius at a Toronto recording studio at a time when Clinton, who headed the band Funkadelic, was enamoured with the sect.

For all this energetic activity, it took a government grant to propel the Toronto chapter to national notoriety.

In 1972, it was revealed that the Process Church in Toronto had received $25,900 in grant money from the Local Initiatives Program. The LIP had been established by the Liberal government to fund cultural and community projects around the country. The Process Church said the funds went to pay for employees at its drop-in centre.

When news of this grant became public, all hell broke loose — so to speak. The PCs bombarded the Liberals with pointed questions. In response to MP Wally Nesbitt, Acting Prime Minister Mitchell Sharp said the grant application “was endorsed” by well-respected organizations including the YMCA, the Doctors Hospital in Toronto, the Department of Health (now the Ontario Ministry of Health), and the Bank of Montreal.

These groups were quick to clarify that they had not endorsed the Process Church per se, but merely signed off on the grant request. Ontario health minister Richard Potter “disowned” a letter from his ministry supporting the grant, stating it had been “written by a junior member of the departmental staff without [his] authority,” wrote the Globe on March 4, 1972.

In similar fashion, the Doctors Hospital said all it had provided was a letter acknowledging that Process Church members performed volunteer work for the organization. (According to the Globe and Mail, “S.J.Johnston, administer of the Doctors Hospital, said his director of volunteers gave a standard letter of acknowledgement after two members of the sect spent one morning a week for seven weeks working with children in the hospital … He said there was no religious overtone to the volunteer’s work.”)

Denying that they had knowingly funded Satanism, the Liberals held firm and “rejected the suggestion that a group’s religious affiliation should be a criterion on whether or not it should get an LIP grant,” wrote the Globe.

In late March 1972, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau told the Commons that “the offices of the local initiatives program gave the [Process Church] grant in good faith to people who seemed to be engaged in doing some good work.”

The Tories wouldn’t let the matter go; during a Commons committee meeting in early 1973, Erik Nielsen (PC-Yukon) read out “two affidavits alleging that a Toronto coffee-house and drop-in centre financed by the Local Initiatives Program last year [and run by the Process Church] was a haven for addicts, prostitutes, homosexuals, and drug traffickers,” stated the Ottawa Citizen.

Toronto Processeans refuted these charges, as well as accusations of devil-worship.

If Wyllie’s account in Love, Sex, Fear, Death is correct, the real grant scandal had more to do with deception than drugs and demonology.

According to Wyllie, a colleague called Phineas discovered “a Canadian government program that promised substantial grants for social work. Without really believing we’d get it, Phineas and I filled in their forms, carefully bending the facts to fulfill the government’s requirements.”

To the chapter’s surprise, the grant was approved. The group quickly transformed the basement of its coffee house into a soup kitchen and began offering free meals to homeless people. Old clothing was gathered and given away to the destitute. The group also counselled drug addicts. In truth, the chapter’s anti-poverty mission was “a half-hearted effort done mainly by us to justify the grant and to enhance our public image,” wrote Wyllie.

Extensive news coverage about the grant did raise the group’s profile. The chapter’s leaders were extensively interviewed by the media; a rock band featuring Toronto Processeans members played regular gigs at Process Church headquarters and other venues.

Despite this burst of publicity, the church’s strange theology hindered mainstream acceptance — in Toronto and elsewhere.

By 1974, the Process Church around the world was engulfed in crisis. Founders de Grimston and MacLean had a falling out, and the latter seized control of the organization. The group changed its name to the Foundation Church of the Millennium, ditched the “love your enemy — the devil” doctrine, and embraced a more mainstream Christian faith. The rebranding didn’t work, and the order faded into obscurity. In 1993, the church adopted another new identity, becoming Best Friends, a non-profit group devoted to animal care.

The Process Church continues to attract notice. The Netflix series The Sons of Sam revived the shaky claim that serial killer David Berkowitz was a member. The church was also profiled in a 2015 documentary called Sympathy for the Devil.

As for the LIP grant — which expired in September 1972 — Wyllie wrote that “credit must go to the Trudeau government in that they didn’t back down, but from our point of view, it just kept all the unpleasant publicity in the news that much longer.”

Unpleasant publicity that made it all but impossible for a fledgling sect with a radical theology to gain a mass following in Toronto the Good.

Sources: the March 27, 1972, edition of the Calgary Herald; the April 17, 1971, February 5, 1973, March 4, 1972, March 9, 1972, March 24, 1973, May 30, 1974, and December 5, 1974, editions of the Globe and Mail; the March 2, 1972, edition of the Leader-Post; Love, Sex, Fear, Death: The Inside Story of the Process Church of the Final Judgment by Timothy Wyllie (Feral House: 2009); the February 2, 1973, and March 2, 1972, editions of the Ottawa Citizen; the May 22, 1971, edition of the Ottawa Journal; the May 16, 1973 and May 22, 1971, editions of the Toronto Star; The Ultimate Evil: The Search for the Sons of Sam by Maury Terry (Quirk Books: 1987).

Also: Wallace Nesbit (PC - Oxford) and the Honourable Mitchell Sharp (Acting Prime Minister), House of Commons Debate, Manpower — Local Initiatives Program, Ottawa, March 1, 1972.

The Right Honourable Pierre Trudeau (Prime Minister), House of Commons Debate, Manpower ‚—Local Initiatives Program — Grant to Process Church of the Final Judgement, Ottawa, March 22, 1972.

Local Initiatives Program (LIP), Connexipedia website

Nate Hendley

Description

Nate Hendley is a Toronto-based journalist and author who has written several books, primarily in the true-crime genre.

https://www.tvo.org/article/when-a-toronto-church-grant-caused-all-hell-to-break-loose-in-1972

No comments:

Post a Comment