Harretz

April 13, 2021

When you talk with Polish photographer and producer Agnieszka Traczewska, you get the feeling that she’s an inseparable part of the ultra-Orthodox Jewish world – even though she’s Catholic.

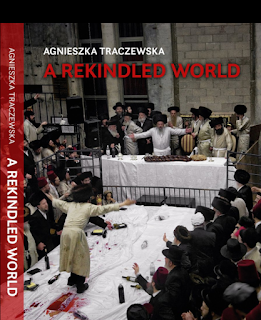

My conversations with her, like the text that accompanies the photographs in her new book, “A Rekindled World,” are peppered with Jewish vocabulary. She knows when to say “chagim” (holidays), “Shabbat shalom” (good Sabbath), “tzni’ut” (modesty), Hasidim, “baruch Hashem” (thank God) and even “refuah shlemah” (best wishes for a full recovery).

Traczewska, who has held some 40 solo exhibitions around the world – including in the United States, Germany, Australia, Brazil and Canada – also easily reels off names of ultra-Orthodox towns and neighborhoods in Israel, from the city of Bnei Brak to Jerusalem’s Mea She’arim neighborhood.

For her previous book, “Returns,” which was published in 2019, Traczewska primarily photographed ultra-Orthodox Jews praying at the graves of holy men in Poland. Her new book is a summation of 12 years of journeying through Hasidic communities in several countries: Israel, the U.S., Canada, Belgium, Britain and Brazil.In an interview with Haaretz that took place over several digital platforms, she says that no one has made the effort to trace where Hasidism has moved from Eastern Europe. She traveled across three continents in an effort to create a portrait of renewed Hasidic life.

Traczewska finished her journey when the coronavirus erupted. The final photographs in the books are from the early days of the pandemic in Europe. In her photos, she focused on Hasidic dynasties that originated in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, especially dynasties that originated in Poland, Hungary and Romania.

She says the secular public sometimes sees all ultra-Orthodox people as an undifferentiated mass, but the reality is very different.

“All Hasidic communities differ with their customs, habits, level of orthodoxy. At once the most surprising was that the Black and White crowd of people, who looked so similar to outsiders, is in fact so complex and various. [There are] endless lessons to learn.”

Thanks to her learning process, she says 95 percent of her closest friends are now Hasidim from around the world, including many in Israel.

“Asked about my second home, I always say ‘Mea She’arim,’ and this is an authentic, honest feeling of belonging to people I met and know there,” says Traczewska. “They [showed me] unprecedented hospitality and trust. Over years they shared with me so many strictly private moments and occasions that not having my own family, I had a total illusion we belonged somehow. You may think, ‘against all odds.’ And that’s true – they are some obstacles, but there are also some similarities between us, which often led to an automatic understanding and feeling of mutual comfort.”

How did you first begin acquainting yourself with each community?

“In every close community, the most effective way to get to know new people is to have somebody who can give a recommendation. In the most distant geographic locations, when it came to the Hasidic community, there was always somebody with whom I had common friends or I knew part of his family from somewhere else. It doesn’t mean I still don’t need to earn their trust, but at least the introduction makes dialogue possible.

“Although we speak about hundreds of thousands, this is a small world, shtetl-like. People know each other and trust only those who belong. Hasidim remember painful lessons of being closer to outsiders who failed [them]. They don’t want to make another mistake.”

A moral obligation

The photographs in Traczewska’s new book show a glorious ultra-Orthodox world that’s very different from the image the community has inside Israel. In these photos, even poverty looks happy, complex, rich and full of life.

Many of the photographs depict customs and mitzvot, or religious commandments, and show masses of congregating Hasidim. She photographed the festivities during the Lag Ba’omer holiday at Mount Meron in northern Israel. One picture taken in New York, looking out at Manhattan from Brooklyn, shows Hasidim performing the tashlich ceremony on Rosh Hashanah. Another, from New York’s Borough Park neighborhood, shows one of the leaders of the Bobov sect, Rabbi Ben Zion Aryeh Leibish Halberstam, flanked by his Hasidim during the Havdalah ceremony marking the end of Shabbat.

Some of the photos are of major events, like the wedding of the son of the Satmar rebbe, Aaron Teitelbaum, in Petah Tikva. A photograph of the Purim celebrations in Mea She’arim shows a group of children in costume as two of them pretend to smoke a cigarette.

Still others document the daily lives of Hasidim. A photo from Bnei Brak taken a few minutes before the start of Shabbat clearly shows how crowded the city is, yet the street is empty of cars and children walk in the middle of it in their best clothes. A photo from Safed shows a baby being bathed in the kitchen sink.

“There are many Hasidim who made my journey meaningful,” she says. “One of the most important couple of Bobov Hasidim whom I met during Tzadik Shlomo Halberstam’s yahrzeit [memorial service] at the cemetery in Bobowa, Poland, are Naomi and Duvid Singers from Borough Park. With roots in Poland and Hungary, [and] long experience in preservation of Jewish heritage projects in Poland, they understood my reasons for portraying places connected with the Great Tzadikim tradition.”

In Sao Paulo, Brazil, “I had the enormous privilege, also thanks to some Hasidic supporters, to meet all the most important Hasidic leaders living there. With one of the rebbes, after an hour of our conversation about Jewish tradition, Great Tzadikim, places and occasions I [had participated in], I started to say goodbye. When he asked me about my trip back and he heard I will travel on Friday, I saw his fear that I may not reach my destination before Shabbos.

“That was a moment when I understood he didn’t realize I wasn’t Jewish, so I told him. He was in shock. Giving me bracha [blessing], in contrast to Hasidic tradition, he ended with, ‘and when you will be ready, please know that the Jewish people invite you.’

“Both of us were moved. Me particularly, as I felt I didn’t disappoint those who put their recommendations in my pocket.”

Traczewska doesn’t view her work as a documentation. “It would suggest that I made some kind of scientific research,” she explains. “I’m not an ethnographer or anthropologist, so documentation wasn’t my aspiration. I didn’t treat Hasidim as objects to test. The artistic approach was important. My intentions were more of a sentimental and historical nature. I tried to record people who have a fascinating history, belonging to the same land I happened to live in.”

She adds that Poland’s communist government tried to erase these people’s history after World War II, and when she learned of this, “I found it mind-blowing and outrageous. My disagreement with propaganda that erased Jewish presence from Polish history was an inspiration and somehow even a moral obligation to make the Hasidic chapter of Polish story visible.”

How did you get close to your subjects?

“When two people meet, even when they can’t talk to each other directly, they obviously have the ability to communicate. Traveling to Hasidic sites, I’m always dressed with tznius in order to signal that I understand and respect the rules. Of course I’m still different, obviously not Jewish, not speaking Hebrew or Yiddish, but at least it was clear to them that I’m not a direct threat. I arrived at a yahrzeit at the graves of Great Tzadikim or at events on chagim with a camera, which gave a clear explanation of what I was looking for.”

Did anyone object to being photographed?

“I never violated somebody’s free will to participate in my projects. For example, taking pictures of Hasidic groups, when I feel that somebody truly objects, I don’t include him in the frame. Keeping and respecting rules was my first rule. Without my gentle touch I would have angry faces, no different from the ones I see in many pictures of Hasidim available in the media. My characters are always praised for being beautiful. Are all of them so pretty? For sure not, but the fact is they let me show their human side, full of warmth, generosity, intimacy, which no doubt isn’t too common in Hasidic photography. It’s a glimpse that was possible because people feel comfortable with me.”

A patriarchal world

Judging by her photographs, Traczewska managed to totally involve herself in the Hasidic world, but she notes that some places are closed to a female photographer because they are for men only. “But over time I understood that this challenge might be eventually overcome thanks to helping hands, important friends or recommendations,” she says. “Of course it doesn’t mean I can be present at any occasion I want in a major place which would be perfect for photography, but still, there are some other angles, some other floors with windows, corridors etc., where I can still make pictures I’m satisfied with.

“For example, on the cover of my new book there is a scene of a Purim tish [Hasidic celebration] celebrated in a synagogue in Beit Shemesh. It was made from the women’s section, through thick brown glass, in a terrible crowd which almost prevented me from seeing anything. But still, eventually I created an illusion that the viewer is inside the scene, which seems so dynamic that it looks as though it’s taken straight from a Shakespearean drama.”

There are almost no women in the book.

“For me, the most important fact is that in spite of Hasidic tradition and a serious ban against showing women, in ‘A Rekindled World’ there is a wide choice of female portraits. Decent close-ups in a pretty intimate, indoor setting, which is so against custom that of course when I was working on the book I could seriously worry [about including them]. I was afraid the whole book will be rejected by Hasidim en bloc.

“Fortunately, now observing the enthusiastic feedback of Hasidim I know, it didn’t happen. Hasidim now write to me that they are proud to see their wives or mothers in my pictures. I truly tried to do justice to not only how they look, but mostly who they were, what philosophy and hardship they represented. I think that was appreciated.”

At the same time she adds, “However, we need to understand that the Hasidic world is a totally patriarchal system, and most of the ceremonies exclude women, so if somebody really would like to count men and women in ‘A Rekindled World,’ there is no way for it to reflect equality. Men are winners when it comes to public recognition.”

What is your opinion of the Hasidic lifestyle?

“Hasidic life embraces a wide spectrum of aspects, almost impossible to be discussed in a few sentences only. Hasidism varies not only because they represent various Hasidic dynasties with differences in customs, rules and mentality. They vary because they live in various parts of the world with different standards of living. It’s very difficult to compare, for example, between Hasidim living in the U.S. and Israel. It’s very helpful to enter the Hasidic world without prejudices and stereotypes.”

And yet, is there anything that seems overly strict to you?

“What was difficult for me? The fact that individuality is almost unknown in the Hasidic world. As I’m very individualistic – self-employed, self-made, traveling alone, doing authors’ projects only – I’ve always regarded the freedom to make my own decisions as the key gift.

“Hasidim are taught that the community gives security and support. A Hasid lives in a constant cycle of occasions which connects him to other fellow Hasidim. They look and behave almost the same. They go through the same stages of life with almost no exceptions and most often it provides them with authentic joy and comfort. Individuality is not wanted, as somebody who stands out may create a threat to identity and the maintenance of tradition, values and rules.

“That was an important step in understanding the Hasidic world, when I realized that my ambitions or aspirations as an outsider don’t have a lot in common with Hasidim, or let’s be frank – nothing at all. To understand them I needed to learn about their motivation, to develop empathy, to do justice in the way I will present them.”

What are you more interested in photographing, everyday life or religious ceremonies?

“Both occasions are different but both are equally important in intense Hasidic everyday life. In a way it’s one of the most fascinating factors of the phenomenon of living side by side with others within a community: There is an endless chain of occasions to meet, talk, go through something together. On the same day people live their ordinary life, sending children to school, working, participating in some family occasions and ending the day with being a part of a massive celebration of the entire community. When I used to stay with Hasidic families, I was totally hypnotized by how much is happening all around, day by day, and it’s all about family and others.

“There’s no problem with being bored or lonely. The wave of constant socializing and celebrating happy occasions, or those that require compassion and support for others, creates a perfect symbol of the cycle of life.

“Most of the Hasidim I know come from families of Holocaust survivors. However, the Shoah is not a subject they discuss with me often or freely. My friends like to talk about their origins in Poland or Eastern Europe. They know their genealogy well, they are interested in documents, archives where they can learn more.

“But not too many talk directly about the cruelty of World War II and the horrible things which happened to them or their families. Maybe it’s too painful to be discussed. Or maybe they feel it may create some evil memories and can lead to animosities between us? They just say – ‘My father was the only one who survived of 200 members of his family sent to Auschwitz.’ And there is no need to say anything more. I’m from Poland and I understand the rest.”

The last pictures she took outside of Poland were in January 2020 in the United States, a moment before the outbreak of COVID-19 all over the world. The new book includes scenes from a synagogue in Krakow in the first days of the pandemic. As opposed to most of the photos in the book, here there are isolated worshipers in a large space that looks abandoned. The book also includes two texts related to the coronavirus, one by Chaim Yaakov Zilberberg – who served as a envoy of the Gur Hasidim in Krakow and was asked to pray in the cemetery for the recovery of coronavirus patients – and a second by Giti and Dov Aharon Yosef Robinson of the Bratslav Hasidim in New York, who discuss the period when Dov Aharon was ill with the virus, until his recovery.

There has been a lot of criticism of the ultra-Orthodox over the past year, both in Israel and in the U.S., for not observing social distancing rules. In the book you try to moderate the criticism.

“That’s not really an issue I can discuss. I spent the entire pandemic in Poland, totally trapped, so everything I know comes from the media rather that firsthand observation. No doubt, my aspiration was to show the ‘human side’ of Hasidism. In the media they’re often shown anonymously, without doing justice to their personal stories, values. The way I show their life – in maximum close-up, with Hasidic texts honestly expressing the way they regard the world – helps a lot in creating empathy and in understanding their differences.”

No comments:

Post a Comment