On a quiet country road outside Toronto, a charismatic martial arts teacher built a megamansion for his entourage of disciples. For 15 years, he preached peace and love. Then, one morning, the police stormed in and secrets came spilling out

H. G. Watson

Toronto Life

February 21, 2023

Christian Dombkowski grew up riding horses on his family’s farm in the German countryside. He had a happy childhood, but then his idyllic life began to unravel. In 1984, when he was 12, his mom and dad separated. Four months later, his older brother died in a car crash. His parents decided to give it another try and start a new life in Canada, but after they arrived, they split again: mother and son in a townhouse in Milton, father in Alberta. Young Christian learned English and made friends hanging around Trevi Pizza, a strip-mall shop that was popular with students thanks to $1.25 slices and a wall of arcade games. He spent so much time there that, when he turned 16, the shop hired him as a delivery driver.

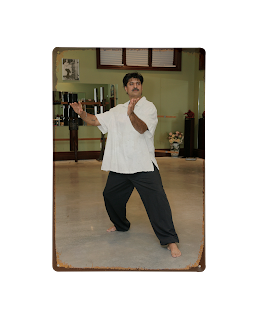

Christian loved Bruce Lee movies, so he was intrigued when he noticed a martial arts dummy in the back room of the shop. He asked around and discovered that it belonged to one of the owners, Mohan Ahlowalia, whom everyone called Jarry. He was in his mid-20s, and like Christian, he’d come to Ontario as a boy. He taught Wing Chun, a form of close-quarters kung fu popularized by Bruce Lee, in a small studio in the basement of his modest bungalow. Christian asked for a lesson, but Jarry declined. When he kept asking, Jarry eventually relented.

As agreed, Christian arrived at Jarry’s house at 7 one evening, but Jarry wasn’t home. His wife, Priti, told the young man that he was welcome to take a seat in the living room. He waited as the clock ticked on—20 minutes, an hour, then two. He was sure that Jarry was doing what martial arts masters always did in the movies: testing their students’ resolve. When Jarry finally arrived, around midnight, he acted like he’d never scheduled a lesson. But Christian seemed committed, so Jarry gave him a brief history of Wing Chun and demonstrated its first stance, a pigeon-toed position called Yee Jee Kim Yeung Ma. If Christian wanted to learn the art’s swift and deceptively powerful movements, he’d have to come back.

He returned for a second class, then a third. They were gruelling. Jarry demanded that Christian repeat movements until he was on the verge of passing out. When he made mistakes, Jarry directed him to do push-ups. It wasn’t punishment, he’d say; it was part of the training. Jarry extended his instruction to the pizza shop, showing Christian how Wing Chun footwork could help him move around the kitchen more nimbly.

As he trained, Christian befriended Jarry’s other students, a group of eight or so teenagers and 20-somethings. They respected Jarry as an elder; when they got Chinese food together, they poured his tea first and paid his bill. When Jarry spoke, they all listened. He extolled the cultivation of qi, or life-force energy, and shared teachings from a melange of faiths: his own Sikh religion, Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, assorted gurus and mystics. Christian believed that Jarry was enlightened and, as the months passed, saw him less as a boss and more as a mentor. He saved Jarry’s teachings in a binder that he studied in his downtime. At Jarry’s request, Christian started running errands for him—a small price to pay for free martial arts classes.

Instead of finishing high school, Christian dropped out to help Jarry start a couple of sandwich shops called Sub Machine. During one of Christian’s shifts, Jarry caught him goofing around, mocking martial arts moves instead of working. He angrily forbade Christian from returning to Wing Chun. A few days later, he lectured Christian on the importance of discipline and training. Throughout the conversation, Christian kept worrying that, without Wing Chun, he’d end up out of shape like his father. At the end of the lecture, Jarry told him that he could return to classes. “Otherwise,” he said, “you’re going to end up looking like your dad—just like you’re thinking about right now.” Christian was dumbstruck.

When Christian was 19, Jarry invited him to move in. Christian’s mother, pleased that her son had picked up a healthy hobby and found a father figure, approved. To Christian, it seemed like a party—a few other students already lived in Jarry’s basement—so he said yes. He slept on the floor with the others; according to Jarry, that was also part of the training. Over the next few years, Christian found a sense of community among his housemates, like-minded postulants who shared his devotion to Wing Chun and their enigmatic teacher.

Christian trusted Jarry implicitly, even with his biggest decisions. When Christian was in his mid-20s, Jarry suggested that he marry Sheela Chandan, a fellow student who had been living in Jarry’s house for longer than Christian. Though they were around the same age, Christian had never considered a romantic relationship with Sheela. He knew that she’d slept with Jarry—he says he heard them having sex and saw Priti screaming at her about it—and that Sheela’s parents had kicked her out because they didn’t approve of her seeing a married man. But Jarry kept pushing them to couple up. “There was no saying no to Jarry,” says Christian. So he put his reservations aside, and in March of 1996, they were married. It felt odd to wed a woman who had slept with Jarry, but Christian knew he could get past it. They were a couple now, he thought, committed to each other.

Later that year, Sheela gave birth to an adorable girl with her mother’s dark complexion and brown eyes. When Christian drove home from the hospital, elated, he hugged Jarry. When they’d met, he was a lonely teen in an unfamiliar place. Now, in his mid-20s, he had a wife, a daughter and a circle of lifelong friends. Thanks to Jarry, he thought, he’d found contentment. He had no reason to suspect that, behind his back, Jarry had already begun to betray him.

Over the next several years, students floated in and out of Jarry’s home. Christian and Sheela had another daughter in 1997 and a boy in 2002. By then, there were 15 people in the house, including Jarry’s teenage daughter and son. The group enjoyed the benefits of a communal lifestyle: training together, cooking for one another, looking after one another’s kids. But everyone agreed that they needed more space.

In the early 2000s, Christian and Jarry went on the hunt for a new home. They visited a 30-acre property in Mount Nemo, a rural community in northern Burlington. The old farmhouse, flanked by a barn and a drive shed, wasn’t big enough to house everyone. But the area, situated on the rise of the Niagara Escarpment, was naturally stunning—green lawns punctuated by wetlands and forests with deer and foxes roaming about. It reminded Christian of the farms he’d grown up on. By then, he had begun working with his father, making up to $300,000 a year selling horse-training equipment around North America. He and some of Jarry’s other followers, who had made money buying, renting and selling real estate, pooled together a $150,000 down payment and bought the property for $550,000. They registered it in Sheela and Priti’s names; that way, it would be safe if the men or their businesses went bankrupt.

The group planned to raze the existing structures and build their new home. The gated mansion would have several thousand square feet of living space across three floors, with six bedrooms and bathrooms, a dining room large enough to seat dozens of people, a spacious martial arts studio with mirrored walls, and a three-car garage plus space for more vehicles out front. The neighbours were apoplectic, and they filed complaints with the Niagara Escarpment Commission, arguing that the mansion was out of place among the neighbourhood’s bungalows and farmhouses and would overstretch the area’s limited water supply: nearby homes relied on personal wells and septic systems. The matter went back and forth, but the house was eventually finished in 2005. Some residents of Mount Nemo Crescent called it “the monster.”

The mansion housed as many as 20 people at a time. They referred to one another as family, and they acted like one: splitting the cost of food, vacationing together, divvying up chores like cleaning the barn and tending to the property’s horses, cows, goats and chickens. But, whenever Jarry needed something, they would drop whatever they were doing to help him. Jarry was the de facto head of the household, taking up residence in the primary bedroom and dictating the rules and rhythms of daily life. Everyone helped with physical labour around the property. A few of the men, including Jarry and Christian, got their gun licences and went shooting at a local range. Women cooked and cared for the kids. They were expected to smell nice and dress beautifully, “like a flower,” as Jarry put it. According to Christian, couples slept in separate beds—they’d get better rest that way, Jarry said—with their bedroom doors open. Wedding bands, which Jarry interpreted as symbols of slavery, were discouraged. He disliked the words “husband” and “wife” and encouraged couples to call each other “companions” instead. People, he said, couldn’t own one another.

During family dinners, Jarry delivered lengthy sermons on spirituality and the importance of sticking together. He was quick to point out how his students could improve whatever they were doing. Having owned several restaurants, Jarry considered himself an excellent cook, and he berated the women of the household when they made even minor mistakes—for instance, using the wrong type of tofu in a dish. Jarry might yell at them or give them the silent treatment. His students rarely challenged his behaviour: the slightest dissent could incite his fury. But, afterward, Jarry often became gentle with the targets of his ire, cryptically telling them that he’d received a message in his sleep saying that they should be more open-minded and make better decisions.

When Christian’s mother and stepfather visited the mansion for dinner, they were alarmed by Jarry’s grip on the family. They questioned why Christian chose to live in such a dictatorial household, obeying Jarry’s every command. Christian had even lost his job with his father because he spent so much time focusing on the family. “Don’t you have your own opinion?” Christian’s stepfather asked him. “There is only one king in this kingdom,” Christian replied. “And his words are law.”

During the family’s first few years at Mount Nemo, Christian considered himself Jarry’s right-hand man. He wasn’t just another student passing through; he was a trusted friend and business partner. But, in the late 2000s, he sensed his status slipping. Jarry started spending less time with him. He says Jarry disparaged him too, telling him that he’d gained weight, that he should eat better and try to lose a few pounds. Christian suspected that the change had to do with the arrival of a new family member: Philippe St-Cyr.

In 2007, Jarry’s daughter had fallen in love with Phil, a former student of her father’s. He was a French-Canadian with blond dreadlocks who’d travelled the world working on boat crews, and he idolized Jarry. Phil moved onto the compound and then became Jarry’s new son-in-law. He and Jarry’s daughter taught yoga classes to outsiders on the property. They made smoothies and desserts for their students and, on Jarry’s advice, started selling packets of nuts, seeds and dried fruits—Phil always had extras because he ordered them in bulk. That proved to be profitable, so the couple started more businesses: a holistic wellness retreat, a microgreens farm, an eco-friendly packaging company now known as Rootree. Jarry pushed his followers, many of whom had full-time jobs, to work for the family businesses. At first, some worked without pay: they wanted to help the fledgling companies grow, and they saw their labour as a trade-off for room and board. Profits went back into the homestead, covering mortgage payments, property taxes, hydro and business expansion. As Rootree grew into a multimillion–dollar business, the family added a storage building with extra housing behind the mansion. Then came a warehouse and packaging facility as long as a football field, complete with a loading dock. The family bought ATVs and a Sprinter van and installed a pool behind the house.

In 2014, Jarry proposed yet another business. He wanted to buy a bar nearby and start a new restaurant in the space. Christian advised against it. Jarry’s previous restaurants had fizzled out, and Christian didn’t want to get back into the industry. But Phil, who was enthusiastic, secured a $200,000 down payment from his father, and the family opened Wundeba, a casual eatery serving smoothies and healthy breakfast options. Jarry’s daughter and Phil managed the business while Jarry reigned over the kitchen with the zeal of a drill sergeant. He cursed at employees and threw bowls across the room when he was frustrated. At least once, his daughter asked him to dial it down, concerned that his fits made the restaurant seem unprofessional.

Women cared for the kids, cooked meals and were expected to dress beautifully. Couples slept in separate beds—they’d get better rest that way, Jarry said—with their bedroom doors open

Almost everyone in the family worked at Wundeba, even if they had other jobs. As at Rootree, many employees were not paid at first; they agreed to forego wages until the place turned a profit. The family tried to create a formal shift schedule, but no one followed it. In 2016, Christian says, he often worked 13 hours a day: he would put in a full day at Rootree and then drive to the restaurant for the evening rush. “I probably aged 10 years in that freaking summer,” he says. By the end of the year, he was exhausted, and he’d grown tired of Jarry’s insults.

Compared with Jarry’s other students, however, he had it easy. No one suffered more of Jarry’s verbal abuse than a woman I’ll call Meera. (Her identity is protected by a publication ban.) Meera had met one of Jarry’s students at art school in 2004 and, within weeks, moved in with the family. At the time, her parents lived outside of Canada, and Jarry seemed like a father figure. Within a year, she had dropped out of college, married one of Jarry’s students and given birth to her first child. “That was the beginning of a long nightmare,” she says.

Meera would later allege in court that, between 2005 and 2019, Jarry physically and sexually assaulted her. She would testify that he smashed her into a door frame because of a mistake she had made while preparing a meal, shoved raw hamburger meat and coleslaw into her face and hair, held a kitchen knife to her chest, touched her breast and vagina in the warehouse, and threatened to bury her behind the house with a dead horse. The court would also hear from multiple witnesses that, at Wundeba, where Meera made salads, smoothies and juices, Jarry called her “bitch,” “cunt,” “whore” and other derogatory names. Christian heard some of these insults, but he held his tongue, fearful that Jarry would turn on him if he spoke up. “Every person’s mission was to make sure they were not in Jarry’s bad books,” he says.

One day in September of 2016, however, Christian says that Sheela came home from the restaurant and told him Jarry had slapped her. (Sheela did not respond to requests for an interview.) Christian was furious. He took Sheela and their son, who was then 14, and decamped to a nearby hotel. (Their daughters, now adults and entranced by Jarry, stayed at the house.) Jarry begged Sheela to return and left dozens of pleading voicemails on Christian’s phone. “It’s almost scary to think you are not in my life,” he said in one. He warned that the family would suffer “heavy consequences” if they didn’t return. In another message, he said, “We are meant to be together for a fucking lifetime.”

Within a month, Christian and Sheela began fighting over whether to return. She found it strange and lonely to be separated from the family, and she believed that Jarry would change. Christian didn’t want her to leave him, so he agreed to move back in. At their first dinner with the family, Christian says, Jarry called them cowards for leaving and told the others that Christian and Sheela weren’t “people of high spirit.”

Back at Mount Nemo, Christian tried to return to the life he knew, but it wasn’t long before another bomb dropped. Twenty years earlier, when his daughters were born, Christian’s stepfather had suggested that the girls, who resembled only their mother, might not be his biological children. Christian refused to consider the possibility. But, one day in 2016, he says, his younger daughter told him that Jarry had claimed to be her real father. Determined to know the truth, Christian took the girls’ toothbrushes, swabbed his son’s cheek and sent their DNA to a lab for testing.

The results arrived by email in November of 2016, while Christian was raking leaves outside Wundeba. He steeled himself as he opened the message. His son, it said, was irrefutably his. But there was a zero per cent chance that he was the girls’ father. “All the energy left my body,” he says. His daughters’ real father had to be Jarry, which meant that Jarry and Sheela had continued to have sex even after she had married Christian. For all he knew, they might still be sleeping together.

Christian says that, when confronted with the DNA results, Jarry admitted to the affair and later offered a half-apology: “Sorry, but look, I live my life.” When Christian called Sheela, who was at a packaging convention in Chicago, she said the results “made no difference” and told him, “Maybe it was God’s will.” Christian was furious. How could she blame this on God?

Christian’s reverence for Jarry morphed into bitter resentment. One day in October of 2017, Jarry was chastising his son for improperly fuelling a chainsaw, a chore that often fell to Christian. Jarry turned to Christian and said, “You didn’t raise him right.” Incredulous, Christian replied, “He’s your son” and goaded Jarry: “Why don’t you and me go downstairs right now?” The two men descended to the training room and broke into a fight. They have different accounts of who struck first. Either way, Jarry’s daughter arrived and broke it up. “It was not the best thing I’ve done,” says Christian. “But it made me feel really good.” Afterward, he and Jarry spent a couple of hours talking, eventually agreeing that they’d have to get along somehow.

Christian spent long hours at Rootree, trying to avoid Jarry. At home, anxious and depressed, he stayed in his room, reading books about cults and sociopaths. He learned what a narcissist was and thought the definition fit Jarry perfectly: an inflated sense of self-importance, a deep need for attention and admiration, a lack of empathy, extreme confidence masking fragile self esteem. He learned that Jarry had lifted some of his teachings from religious texts, including the writings of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, more famously known as Osho, the leader of the violent commune documented in the Netflix series Wild Wild Country.

Christian was in profound shock. How could Jarry, his kind, enlightened mentor, be the same man who had lied to him and betrayed him? He remained at Mount Nemo for two years, trying to understand how he’d been so badly deceived. Had Jarry just used him for his money? Had he set him up with Sheela to keep her close? It went as far back as the night he had waited for his first Wing Chun lesson. If that had been a test, Christian thought, he’d proven his unquestioning loyalty. As he rode horseback around the property he had once considered a paradise, he couldn’t shake the feeling that he had built himself a prison.

In December of 2019, one of Jarry’s former disciples reached out to Christian with startling news. Meera had reported the alleged assaults to the Halton police. They were coming to arrest Jarry.

At 6:30 a.m. on December 20, Christian got out of bed and gathered his things. It was a grey day. Snow blanketed the ground. He got into his car, pulled out of the driveway and drove to Rootree’s offsite warehouse. A few kilometres north of the house, he saw a convoy of Halton Regional Police cruisers and tactical unit trucks. At work, he sat in front of a blank computer screen and waited for a call. It came at five to eight. “Jarry is being arrested,” Sheela told him in disbelief. The police cuffed Jarry, who was in his white Ford F-350 in front of the house. In the back seat of the truck, officers found a brown bag containing a loaded silver Beretta. Searching the house, they found more weapons: two guns and ammunition in Jarry’s armoire as well as brass knuckles in his nightstand, next to his passport.

Jarry was charged with 30 criminal counts, including various forms of assault against Meera and her daughter; uttering threats; a number of firearm offences; and human trafficking, for lack of remuneration and using fear to exercise control over Meera’s movements. Jarry denied all the charges and was released on bail in February of 2020. On the Wundeba Facebook page, one family member wrote, “Jarry, our father, friend and relative is a family person with whom we are very close, and who has not committed the alleged offences. The further statements and comments made online in response to the news are so ludicrous that if this was not such a difficult time for us we would find them hilarious.”

As they awaited Jarry’s trial, the family splintered. Christian moved out of the house with his 17-year-old son, leaving Sheela and the girls behind. He launched a civil suit against the family businesses, claiming $650,000 in damages, intrusion and unpaid labour; he says he helped finance Rootree, provided it with software and equipment, and understood himself to be a part owner. Meera, who had left a day before Jarry’s arrest, filed her own suit for $500,000. When the criminal trial began, in June 2021, the battle lines were clear. The Crown called upon Christian, Meera, her husband, another defector and a Wundeba server to testify. Phil, two of Jarry’s daughters and two people who still lived at Mount Nemo would be witnesses for the defence. Jarry’s fate was now in the hands of the judge, Jaki Freeman.

The Crown argued that Jarry had kept guns to protect himself from Christian. Jarry’s lawyer presented another theory: they had been planted

Meera, the first to take the stand, testified that she had decided to go to the police about the years of alleged assaults in October of 2019, when Jarry, she claimed, threw her into a juicing machine at Wundeba, lifted her by her neck and caused her to wet herself. But, under cross-examination, discrepancies emerged. Meera said an alleged sexual assault occurred in the warehouse between 2005 and 2007, but the warehouse wasn’t built until 2009. She described an eye injury as a “cut to the bone,” but medical records specified that there was no bone exposure and that she’d reported the gash as an accident. (She said Jarry had told her to lie.) Meera said that several family members, including her husband and Christian, had been present during specific instances of abuse, but when those witnesses took the stand, they didn’t corroborate her claims. Two people said that they’d seen Jarry jab Meera with his knuckles in the kitchen—incidents that were not specifically included in the charges—but no one testified that they’d seen any other assaults.

Later in the trial, Meera’s teenage daughter testified that, when she was between the ages of eight and 11, Jarry had slapped her so hard that it had left her with a black eye. But Jarry’s daughter and Phil said under oath that they believed the injury had come from playing sports at school. Pressed to explain, the girl admitted that her recollection of the event was fuzzy. “I kind of remember having a black eye,” she said. “I don’t fully remember.” In court, Meera’s daughter also provided details that she hadn’t told the police or the Crown in pre-trial interviews: around the same time as the black eye, she said, Jarry had picked her up by the neck, which had caused her to urinate—an allegation that mirrored her mother’s. Upon further questioning, both she and Meera’s husband admitted that they’d violated instructions to not discuss the details of the case outside of court. Jarry’s lawyer, Jeffrey Manishen, suggested that Meera’s daughter was parroting her mother’s story.

The guns found in Jarry’s bag and bedroom seemed like damning evidence, but they also turned into a problem for the prosecutors. Christian testified that, around 2002, Jarry had asked “a student” to buy three firearms in the US and smuggle them back into Canada. Then, under cross-examination, Christian reluctantly conceded that “the student” was him. Manishen then suggested that, because Christian had bought the illegal guns, he had a motive to make it seem like they belonged to Jarry.

The Crown argued that Jarry had kept the guns to protect himself from Christian, but Manishen presented another theory: they had been planted. Meera’s husband, a private investigator, had provided mountains of evidence to the police, including information on the residents of the mansion as well as photos and videos that seemed to indicate that Jarry kept guns in his bag and bedroom. Manishen suggested that Meera’s husband, who knew when police planned to arrest Jarry, could have accessed a safe where guns were kept. Could he have planted them at just the right moment? No witness testified that they’d seen such a thing, but the suggestion shook the Crown’s case. After all the evidence was heard, the Crown stayed 14 charges. In other words, they were no longer seeking a conviction on nearly half the counts.

On November 15, 2022, more than a year after the trial began, Jarry and his followers packed into a Burlington courtroom to hear Freeman’s verdict. “This case turns on the credibility of the witnesses,” she wrote in a 200-page decision before methodically dissecting the reliability of Christian, Meera, her husband and daughter, and others.

Of the trial’s 14 witnesses, Freeman found only seven to be fully credible: the Crown’s police witnesses, three Wundeba employees and Phil, whose testimony was not seriously challenged. (Phil did not respond to requests for an interview.) Due to inconsistencies in Jarry’s daughters’ testimonies, Freeman explained, they could only be considered reliable if others corroborated their evidence. Meera’s husband, she wrote, “took an unusual interest in the prosecution of Mr. Ahlowalia and, as such, was not a credible witness.” Meera was not credible either because she frequently answered direct questions with tangents that seemed designed to portray Jarry in a poor light and because, on the stand, both she and her husband contradicted or added to what they’d told police and the Crown before the trial. Freeman also approached Christian’s testimony with caution in part because he had lied about buying the guns.

Though Freeman did not accept the gun-planting theory as fact, she considered it a reasonable inference. She also said it was possible that three Crown witnesses, including Christian and Meera’s husband, had colluded to incriminate Jarry. On the assault charges, she noted that, while Meera’s allegations were not seriously undermined, they weren’t corroborated either. “It would be dangerous to ground a conviction on any count where such a conviction rests solely on [her] evidence,” she wrote.

Without a clear finding on the alleged assaults, Freeman gave little credence to the Crown’s suggestion that Jarry had engaged in human trafficking—that he had exerted control, direction and influence over Meera’s movements for the purpose of exploiting her. Though many Rootree and Wundeba employees were initially unpaid, most eventually received wages. In April of 2017, Meera began earning $240 every two weeks; the following year, that increased to $1,133 (half of which went back into a communal house fund), and she began receiving benefits and up to eight weeks of vacation pay annually. Freeman noted that Meera had benefited from the support of the Mount Nemo community and that Jarry had twice encouraged her to move out. In other words, she hadn’t been held against her will. “The Crown’s theory on this count is extremely far reaching,” Freeman wrote.

When she delivered her verdict—not guilty on all remaining counts—the family erupted in cheers and swarmed Jarry. Some were in tears as they hugged him. A few minutes later, he walked out of the courthouse a free man.

In early December, I reached Jarry by phone. His grandchildren were laughing and playing in the background. “It’s been a very hard three years,” he said. “I am, to be honest, quite confused about the whole thing and how far it went.” He declined an in-person interview but told me that I could send him questions by email. When I did, he wrote back, “For almost three years, I lived under the cloud of allegations made against me by several people…. All aspects of my life, both personally and professionally, were significantly harmed.” He recounted the result of the court process and summarized Freeman’s take on Christian’s testimony. “With all that I have been through, I have no desire to respond to what others have said about me. Rather, my energies and focus are directed on the future—to support my family, contribute to the community and work to rebuild my life.”

Meera, who has since divorced her husband, chose not to read the verdict. She believes she knows what it contains, and she rejects Freeman’s reasons for doubting her credibility. She says it was difficult to remember the precise dates of events that took place so long ago: “It’s ridiculous to think a person would have an exact time-stamp on when they were abused.”

The last time I spoke to Christian, he told me, “I have no words for this decision.” He denied that he had colluded with other witnesses. He now lives with his son and his new girlfriend in Stoney Creek. He’s back on the road as a management consultant. His civil suit, as well as Meera’s, is ongoing, and he is still in the process of divorcing Sheela. Though he no longer speaks to her or the girls, he stays in touch with a few of Jarry’s former students and keeps tabs on the family. He wants to move on, but he can’t quite break away. He told me that he couldn’t watch the trial because he felt sorry for his old friend and mentor. Even after everything, a small part of him still feels loyal to Jarry.

This story appears in the February 2023 issue of Toronto Life magazine.

https://torontolife.com/deep-dives/the-guru-of-mount-nemo-inside-a-burlington-commune-gone-wrong/

No comments:

Post a Comment