Time

March 8, 2023

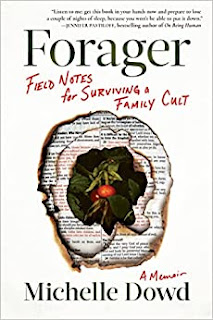

Dowd is a professor of journalism and author of FORAGER: Field Notes for Surviving a Family Cult

Our Mother let us wander anywhere we wanted in the Angeles National Forest when we moved there as small children in 1976. She didn’t restrict where we went, and didn’t ask us what time we would return, but she did tell us what to do if we ran into trouble.

“Never put your hands or feet anywhere you can’t see. If you need to step over a log, step up on it, look, then step down.”

She told us to watch for rattlesnakes and when we encountered an animal that could hurt us, our options were to fight, flight, or freeze.

Our Mother taught me to be vigilant and cognizant of my environment, to look where we wanted to go, and how to find what we needed, wherever we were. She used the phrase “survive fear, survive with faith” (shelter, fire, signal, water, food), to prioritize the basic needs we should meet to survive in the wilderness.

Among the important things I learned out in the wild: Apex predators are omnivores and have lots of options. If they surmise you’ll put up a fight, they’ll likely opt for smaller prey. But if you encounter a black bear, don’t look it in the eye. Just back away slowly. If you encounter a brown bear, roll up in a ball. Either way, don’t be afraid, our Mother would say. Be competent.

To this day, I think of the way Mother froze around Dad, acting confident and unaffected when his anger flared. When the predator was significantly bigger than we were, we knew not to fight or run. Freezing would reduce the severity of injury.

We were told our group wasn’t a cult because we believed in the one, true God, not a human. But there was only one person in our community who had direct access to God, and that person, Grandpa, was the ultimate authority. All the children in our group, even those unrelated to us, called him Grandpa, because he was God’s appointed patriarch. He decided what the Bible meant, who was obeying and who wasn’t, who could stay in our group and who must leave. No one could work outside the Field without his permission; he determined who received money and who did not, and he punished non-compliance. When he kicked my little brother in the head for falling asleep during a sermon, no one questioned him.

What Mother taught her daughters was different from what boys were taught at the Field, and we weren’t allowed to talk about what we knew. Unlike the Mountain, where Mother ruled, the Field was patriarchal. At the Field, the leaders removed all the flora and fauna to create an empty expanse of grass—the antithesis of an ecosystem. The boys were taught to demonstrate physical superiority, to vie for it, to pummel one another in tackle football practice, which they were all required to play, starting at age five, getting accustomed to taking pain and being in the sun without water. They practiced domination as social bonding, like sucker-punching each other or kicking one another’s legs out from behind. They strapped their gear and sleeping bags on their backs for long hikes and bike rides, sometimes riding all the way from the Field up to the Mountain, which is more than 75 miles of roads. They played chicken-fights on fields and in lakes, mastered Snake in the Grass and King of the Mountain, snowball fights and rubber-band gun wars. And they were all required to fight one another in boxing matches, which were part of tournaments, pitted against each other to find out who was the toughest.

Being tough for a girl was different. We spent long days enduring the abuse of boys, but the way Mother navigated the mountain was like the way she flowed through the gauntlet of Grandpa and her brothers, who enforced our silence. In all terrain, Mother moved like water.

I wanted to be like water, because water is strong enough to wear down anything, and other than air, water is the most important thing for humans to have. You can live weeks without food, but you can’t live long without water, especially in hot areas, where you’ll lose large quantities of valuable water daily, sweating. Even in cold areas, your body needs two quarts of water daily to maintain efficiency. But you can get most of that from plants, if you know which ones to eat. In case we got lost and couldn’t make it back for the night, my sisters and I would repeat back to our mother, “Survive fear. Survive with faith,” which helped us remember shelter, fire, signaling, water, food. We knew if we found ourselves stranded, we should attend to our needs in that particular order.

We knew the boundaries of our mountain, and we knew where we’re supposed to stop, although no one ever checked to make sure we did. We waded through the pine needles to walk up the gully from the lower camp to the campfire ring, then on through the remnants of the upper camp to the chapel, and then up to the water tower, and then to a road. Beyond that, I didn’t know what there was. The trees appeared to be endless.

No matter how far I went, I felt safe on our mountain, where I knew the shape of the landscape, where my feet knew the shape of the hills, where the ground was always firm beneath me. I felt safe because the rules in nature are simple, because plants and animals do what their instincts tell them to, and we knew what to expect from them.

At the Field, we were trained to dissociate from nature and from our bodies, overriding our instincts. Grandpa required lifelong members to give up their identities and personal desires to become part of his Family, after which they would always know what was the “right” thing to do because he told them what that was. Cults and other high-control groups are known to provide a deep sense of security and a place of belonging. There is something extraordinarily comforting about belonging to a community where everyone shares the same values, and someone else takes responsibility for your choices. When you relinquish control, and don’t question your superiors, you don’t have to make decisions.

But there is a cost to unquestioning compliance. What you bury, grows.

The last time I was the recipient of sexual violence was seven years ago. A man grabbed me and I went limp, eventually curling myself into a ball on the concrete. When he was finished with me, I didn’t go to the hospital. I went home, covered my body and sat in the dark, shaking with shame. Weeks later, when I didn’t get better on my own, I went to a doctor, who ordered x-rays and suspected my broken bones weren’t from the kind of accident I vaguely hinted at. She called for a social worker, who prescribed trauma therapy, where I went for three years, learning, for the first time, to talk openly about my upbringing and how we were treated as girls on the Mountain.

At the Field, on the other hand, we obeyed the leaders without question or criticism. We shunned former members, relied on shame cycles and secret rituals to keep each other in line, and were paranoid about the outside world and the Outsiders who inhabited it. We learned to hide who we were and trust no one.

“Look where you want to go.” Mother’s mantra to “survive fear, survive with faith” has served as a pragmatic and emotional reminder that if you look around you, you can find what you need. You just have to know what you’re looking for.

The survival skills I learned on the Mountain taught me to trust nature over culture, and I have relied on them over and over during my decades of healing, overriding the systems of violence under which I was raised.

After all, we are made for recovery.

Adapted from FORAGER: Field Notes for Surviving a Family Cult © 2023 by Michelle Dowd. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books.

https://time.com/6260815/growing-up-in-cult-survival-skills/

No comments:

Post a Comment