The Serb warlord was captured in 2008 after a 13-year manhunt that involved the CIA, the SAS and a soldier dressed as a gorilla. As the Hague war crimes tribunal prepares its judgment, Julian Borger describes how the trail led to the door of a bearded therapist in Belgrade

Julian Borger

Julian Borger

The Guadian

March 22, 2016

It has been just over two decades since genocide was last perpetrated on European soil, a discomfiting memory that has been largely buried in a continent now intent on stopping the arrival of escapees from more recent mass murder. Europe’s killing fields are now impromptu camp sites for Syrian refugees.

The amnesia about the continent’s capacity for slaughter will be broken in The Hague on Thursday, where judgment will be passed on Radovan Karadžić for charges of genocide and crimes against humanity during the 1992-95 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It will be a historic moment in the 24-year history of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), often called the Hague war crimes tribunal. For international justice as a whole, it will arguably be the most important moment since Nuremberg.

A guilty verdict is expected by almost everyone involved in the case. Karadžić had, after all, put himself at the head of a breakaway Serb statelet, an entity dedicated to “ethnic cleansing”, the Orwellian term for the systematic use of terror against Bosnian Muslims and Croats. The remaining doubts concern the details and, in particular, whether the highly emotive, politically resonant charge of genocide will be made to stick, and on how many counts.

What is certain is that the defendant will revel in the event. This grandiloquent psychiatrist-poet, a bear of a man with waves of white hair, has played the role of national martyr throughout the proceedings. He is largely derided or forgotten among Serbs in Bosnia and inSerbia itself, but his swansong performance could present the chance of a comeback, an opportunity to tap into a reservoir of victimhood. More than 20 years after the end of the conflict, Bosnia is more divided than ever.

Thursday’s verdict will be a reminder of the scale of the killings – some 100,000 people died in Bosnia alone, with other victims in Croatia and Kosovo – and of the glacial pace at which justice has arrived. The long wait is due in part to the nature of the court, which has strived to be meticulously even-handed, allowing defence lawyers considerable latitude in drawing out the trial. The trial lasted five years, and the bench has taken an additional 18 months to arrive at its verdict.

However, the greatest delay was the 13 years it took to arrest Karadžić and bring him to The Hague for trial. For the first two years following his initial indictment, in July 1995, he was able to live quite openly in the alpine village of Pale outside Sarajevo, which served as the capital of the Bosnian Serbs’ breakaway republic during the conflict. Even though there were 64,000 Nato-led peacekeepers in the country after the war, there was no political will to risk either peacekeepers or the peace itself on arrest operations. By the time that changed, in 1997, Karadžić had slipped into hiding, where he managed to stay until 2008, despite the best efforts of a heavily armed, deeply resourced multinational posse. As Bill Clinton approached the end of his second term in 2000, he saw capturing Karadžić as a pillar of his foreign policy legacy. A special task force inside the National Security Council was told to put new urgency into the search operation, with no expense spared. Before 9/11, the pursuit of Balkan war criminals involved the biggest deployment of special operations troops anywhere, involving Delta Force, Seal Team 6, and the SAS. Karadžić was their number-one target and a priority for the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency and MI6. He was the world’s most-wanted man.

The lessons learned in the manhunt for Karadžić and his fellow warlords were carried forward to Afghanistan, Iraq and the pursuit of Osama Bin Laden, for the most part without the UN resolutions that provided legal underpinning for arrest operations in the Balkans.

David Petraeus, the future US commander and CIA director, was an army brigadier general at the time. Stationed in Sarajevo, he became fascinated by special forces methods there and insisted on going on a night raid with them. “One day, I put him on a helicopter and dressed him up [in civilian attire] and a ball cap,” the man leading the hunt, Lieutenant Colonel Andy Milani, told Paula Broadwell, Petraeus’s biographer, whose affair with her subject would end his career. After a trip across eastern Bosnia’s vertiginous highlands, the helicopter was met by Milani’s Delta Force soldiers. “We jumped in a van with blacked-out windows, and you could tell he was like a kid in a candy store,” Milani said.

Petraeus and his men would make unannounced visits in the middle of the night to Ljiljana Karadžić, the fugitive’s wife, with the aim of rattling her with a show of bravado about his imminent capture, in the hope she would rush to warn him, and give away his location. Petraeus called it his Eddie Murphy routine (after Murphy’s role as convict-turned-cop in the movie 24 Hours). However, Balkan reality did not work like Hollywood. Ljiljana was followed wherever she went and was one of the first targets of surveillance drones, a new toy US special forces were trying out in Bosnia. But she led them on a wild goose chase.

Delta Force soldiers lay in wait for his convoy on a mountain road, one of them dressed in a gorilla suit

The manhunters used every trick they could think of, scanning the remote villages along the Bosnia-Montenegro border for signs of unusual activity – internet logons in the middle of the night, TV satellite dishes in otherwise poor settlements, newspaper subscriptions. The NSA was persuaded to waive normal practice and allow intercept intelligence to be shared, unfiltered and without delay, with the operational units tracking Karadžić in Bosnia.

In one of the more bizarre episodes of the chase, Delta Force soldiers lay in wait for his convoy on a mountain road, one of them dressed in a gorilla suit, which had been flown in from the US the previous day. The idea was that Karadžić’s bodyguards, known as the Preventiva, would be dumbfounded and slow down their vehicle long enough for the Delta Force ambushers to fire a specially designed concussion grenade at the car doors to stun the passengers. The daring scheme would have gone down in Delta Force history, but the central player in the drama failed to turn up. Not for the first time or the last, the initial tip-off had been mistaken, or more likely, deliberately misleading. Karadžić and his supporters took delight in pulling the collective chain of the world’s most powerful military machines.

The elusive quarry deepened the West’s humiliation by using his time in hiding to hit something of a literary peak. Karadžić published a collection of poems, in which one section was titled I Can Look for Myself. His novel, Miraculous Chronicles of the Night, sold out at the Belgrade International Book Fair.

Wanted posters issued for Karadžić and Ratko Mladic. Photograph: Danilo Krstanovic/Reuters

Years later, after interrogating members of Karadžić’s inner circle, the war-crimes tribunal’s own investigators came to the conclusion that Karadžić had left Bosnia for Serbia on Christmas Eve 1999, crossing the Drina River border by boat after nightfall. In that case, the Clinton administration’s intensified manhunt – with all its gadgets, elite units and elaborate schemes – came too late. The prize horse had already bolted.

After Karadžić arrived in Serbia, the picaresque tale became even more bizarre. The trail went cold until 2005, when a self-styled spiritual healer and clairvoyant, Mina Minic, answered a ring on his doorbell in Belgrade to find himself face-to-face with a tall man with a long bushy beard, abundant white hair done up in a top-knot tied with a black ribbon. He looked “like a monk who had done something wrong with a nun,” Minic would recall later.

It was Karadžić, trying out a new identity provided by sympathisers in Serbian intelligence. He introduced himself as Dragan Dabic, a therapist who had just returned home from a stint in New York following an ugly split with his wife. Regrettably, she had refused to forward his professional credentials. Dabic was eager to learn the ways of a Balkan seer, including the use of a visak, a pendulum that is supposed to identify disturbances in the energy field around sick or troubled patients.

Dabic soon acquired his own visak, and his career as a mystic healer blossomed. He adopted the un-Serb middle name of David and used it increasingly as a professional moniker. He also set up a website called Psy Help Energy which advertised the David Wellbeing Programme.

He got involved in a project with a Belgrade sexologist aimed at rejuvenating the sperm of infertile men

Among other services available were acupuncture, homeopathy, “quantum medicine” and traditional cures. He also sold necklaces he called Velbing (well-being): lucky charms that he claimed offered health benefits and “personal protection” against “harmful radiation”. Karadžić had studied psychiatry in Sarajevo and had dabbled in the softer end of therapy. In the 1970s for a while he served as the in-house psychiatrist to the city’s multi-ethnic football team, with the optimistic goal of instilling in the struggling side a will to win, and later played the same role for Red Star Belgrade. The Sarajevo players remembered him making them lie on the floor in a darkened room while he played taped music and told them to imagine themselves as bumblebees flying from flower to flower. To create Dabic, he took this experience and embellished it with New Age concept of the “life force “the life force”, “vital energies”, and “personal auras.” In his spare time, he got involved in a joint project with a well-known Belgrade sexologist aimed at rejuvenating the sperm of infertile men. It was claimed that sluggish sperm would start moving faster if Dabic placed his hands in their vicinity.

He lived in one of the high-rise apartment blocks that lined Yuri Gagarin Street, named in honour of the first man in space, in the shabby remains of the concrete Socialist dream that was New Belgrade. The local kids called him Santa Claus, the kindly old man who would stop and talk to them on the way to the corner grocery store. One of Dabic’s neighbours, who had a flat across the stairwell from him, was a woman who worked for Interpol and whose job it was coordinate the hunt for international fugitives such as Karadžić.

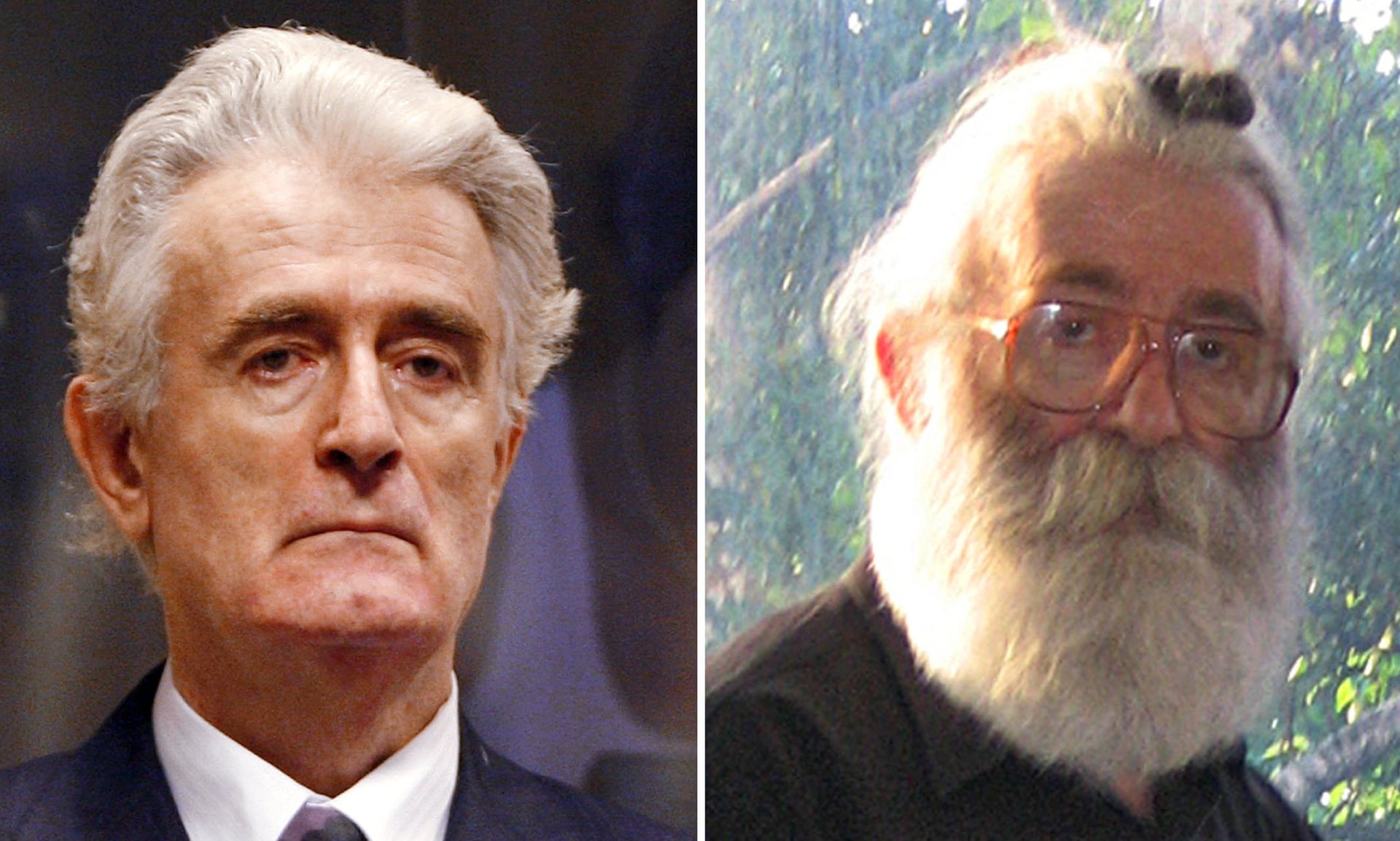

Karadžić (left), while living as Dragan Dabic. Photograph: STR/AFP/Getty Images

As his confidence in the disguise grew, he became ever more daring. He emerged as something of a star on the Serbian alternative medicine circuit, publishing a regular column in Healthy Living magazine, and securing a franchise to represent a US vitamin company in the region. He also started visiting his local bar, the Luda Kuca (“Madhouse”), a smoke-filled, rough-edged place that appealed to a shifting crowd of impoverished war veterans, Bosnian Serbs and Montenegrins. It served country wine,šljivovica (plum brandy), and pungent, undiluted nationalism. On the wood-panelled walls were pictures of the Serb modern nationalist pantheon, with pride of place reserved for Radovan Karadžić.

On at least one occasion he was persuaded to pick up a gusle, the single-stringed fiddle of the region, and perform an epic Serb ballad under a framed portrait of himself at the height of his power. Yet no one recognised him.

In the end, this epic feat of hiding in plain sight was brought crashing down by a slip by Karadžić’s businessman brother, Luka. Late one night in the spring of 2008, he called Dabic with a phone using an old Sim card that the war-crimes investigators had on their records as being associated with the Karadžić support network, and had passed on to the Serbian intelligence services (BIA).

In May, an investigator was dispatched to check on the recipient of the call, this strange Gandalf-like figure in New Belgrade, and the penny dropped. The investigator and his colleagues then had to ask themselves what to do next. Like the rest of the Serbia, BIA was in transition. There was a pro-western reformer in the presidency, Boris Tadić, but the parliament and many of the key posts, including the top intelligence posts, were still in the hands of nationalists. The investigators gambled their careers and, instead of going to their own bosses, took their suspicions to Tadić’s office, and kept up their surveillance. But Karadžić’s fate still hung in the balance. It was only when Tadić was able to put together a liberal coalition, three months after May parliamentary elections, that he was able to replace the BIA leadership with his own man.

By this time, Karadžić was aware he was being watched. According to his lawyer, Sveta Vujacic, the fugitive began to spot unfamiliar faces in mid-July, brushing past him on the stairwell at his apartment block or at the Luda Kuca. “He knew he was encircled,” Vujacic recalled.

On the evening of 18 July, the man known as Dragan Dabic left 267 Yuri Gagarin Street in a light-blue T-shirt and a broad-brimmed straw hat pulled low over his face. He was weighed down with baggage: a white plastic bag, a raffia shopping basket and a knapsack, all of which appeared to be full. He walked to a nearby bus stop where he was soon discreetly joined by one of his BIA trackers. They both boarded the number 73 bus bound for Belgrade’s northwestern suburbs. Dabic sat towards the front. His shadow was several seats back.

When they reached the greenbelt around the Serbian capital, a couple of patrol cars steered in front of the bus and four plainclothes policemen boarded, two in the front and two in the back. They made their way toward the middle, posing as inspectors, showing their badges and asking to see tickets. The old man in the straw hat was reaching into his pocket for his fare when he felt a policeman’s grip around his arm.

“Dr Karadžić?” the policeman asked. “No, it’s Dragan Dabic,” the man protested. “No, it’s Radovan Karadžić,” the policeman insisted.

“Are your superiors aware of what you are doing?” the man asked.

“Yes, fully,” came the reply.

The officer ordered the driver to stop the bus, and the captive was escorted onto the grass shoulder. At 9.30pm on 18 July 2008, the flamboyant fiction that had been Dragan David Dabic evaporated. In his place, the ghost of Radovan Karadžić, the former high priest of “ethnic cleansing” who had haunted the Balkans for a decade, rematerialised on a Belgrade roadside as a flustered old man, his straw hat askew, clutching a white plastic bag to his breast.

Adapted from The Butcher’s Trail by Julian Borger.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/22/the-hunt-for-radovan-karadzic-ruthless-warlord-turned-spiritual-healer

March 22, 2016

|

| Radovan Karadžić |

The amnesia about the continent’s capacity for slaughter will be broken in The Hague on Thursday, where judgment will be passed on Radovan Karadžić for charges of genocide and crimes against humanity during the 1992-95 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It will be a historic moment in the 24-year history of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), often called the Hague war crimes tribunal. For international justice as a whole, it will arguably be the most important moment since Nuremberg.

A guilty verdict is expected by almost everyone involved in the case. Karadžić had, after all, put himself at the head of a breakaway Serb statelet, an entity dedicated to “ethnic cleansing”, the Orwellian term for the systematic use of terror against Bosnian Muslims and Croats. The remaining doubts concern the details and, in particular, whether the highly emotive, politically resonant charge of genocide will be made to stick, and on how many counts.

What is certain is that the defendant will revel in the event. This grandiloquent psychiatrist-poet, a bear of a man with waves of white hair, has played the role of national martyr throughout the proceedings. He is largely derided or forgotten among Serbs in Bosnia and inSerbia itself, but his swansong performance could present the chance of a comeback, an opportunity to tap into a reservoir of victimhood. More than 20 years after the end of the conflict, Bosnia is more divided than ever.

Thursday’s verdict will be a reminder of the scale of the killings – some 100,000 people died in Bosnia alone, with other victims in Croatia and Kosovo – and of the glacial pace at which justice has arrived. The long wait is due in part to the nature of the court, which has strived to be meticulously even-handed, allowing defence lawyers considerable latitude in drawing out the trial. The trial lasted five years, and the bench has taken an additional 18 months to arrive at its verdict.

However, the greatest delay was the 13 years it took to arrest Karadžić and bring him to The Hague for trial. For the first two years following his initial indictment, in July 1995, he was able to live quite openly in the alpine village of Pale outside Sarajevo, which served as the capital of the Bosnian Serbs’ breakaway republic during the conflict. Even though there were 64,000 Nato-led peacekeepers in the country after the war, there was no political will to risk either peacekeepers or the peace itself on arrest operations. By the time that changed, in 1997, Karadžić had slipped into hiding, where he managed to stay until 2008, despite the best efforts of a heavily armed, deeply resourced multinational posse. As Bill Clinton approached the end of his second term in 2000, he saw capturing Karadžić as a pillar of his foreign policy legacy. A special task force inside the National Security Council was told to put new urgency into the search operation, with no expense spared. Before 9/11, the pursuit of Balkan war criminals involved the biggest deployment of special operations troops anywhere, involving Delta Force, Seal Team 6, and the SAS. Karadžić was their number-one target and a priority for the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency and MI6. He was the world’s most-wanted man.

The lessons learned in the manhunt for Karadžić and his fellow warlords were carried forward to Afghanistan, Iraq and the pursuit of Osama Bin Laden, for the most part without the UN resolutions that provided legal underpinning for arrest operations in the Balkans.

David Petraeus, the future US commander and CIA director, was an army brigadier general at the time. Stationed in Sarajevo, he became fascinated by special forces methods there and insisted on going on a night raid with them. “One day, I put him on a helicopter and dressed him up [in civilian attire] and a ball cap,” the man leading the hunt, Lieutenant Colonel Andy Milani, told Paula Broadwell, Petraeus’s biographer, whose affair with her subject would end his career. After a trip across eastern Bosnia’s vertiginous highlands, the helicopter was met by Milani’s Delta Force soldiers. “We jumped in a van with blacked-out windows, and you could tell he was like a kid in a candy store,” Milani said.

Petraeus and his men would make unannounced visits in the middle of the night to Ljiljana Karadžić, the fugitive’s wife, with the aim of rattling her with a show of bravado about his imminent capture, in the hope she would rush to warn him, and give away his location. Petraeus called it his Eddie Murphy routine (after Murphy’s role as convict-turned-cop in the movie 24 Hours). However, Balkan reality did not work like Hollywood. Ljiljana was followed wherever she went and was one of the first targets of surveillance drones, a new toy US special forces were trying out in Bosnia. But she led them on a wild goose chase.

Delta Force soldiers lay in wait for his convoy on a mountain road, one of them dressed in a gorilla suit

The manhunters used every trick they could think of, scanning the remote villages along the Bosnia-Montenegro border for signs of unusual activity – internet logons in the middle of the night, TV satellite dishes in otherwise poor settlements, newspaper subscriptions. The NSA was persuaded to waive normal practice and allow intercept intelligence to be shared, unfiltered and without delay, with the operational units tracking Karadžić in Bosnia.

In one of the more bizarre episodes of the chase, Delta Force soldiers lay in wait for his convoy on a mountain road, one of them dressed in a gorilla suit, which had been flown in from the US the previous day. The idea was that Karadžić’s bodyguards, known as the Preventiva, would be dumbfounded and slow down their vehicle long enough for the Delta Force ambushers to fire a specially designed concussion grenade at the car doors to stun the passengers. The daring scheme would have gone down in Delta Force history, but the central player in the drama failed to turn up. Not for the first time or the last, the initial tip-off had been mistaken, or more likely, deliberately misleading. Karadžić and his supporters took delight in pulling the collective chain of the world’s most powerful military machines.

The elusive quarry deepened the West’s humiliation by using his time in hiding to hit something of a literary peak. Karadžić published a collection of poems, in which one section was titled I Can Look for Myself. His novel, Miraculous Chronicles of the Night, sold out at the Belgrade International Book Fair.

Wanted posters issued for Karadžić and Ratko Mladic. Photograph: Danilo Krstanovic/Reuters

Years later, after interrogating members of Karadžić’s inner circle, the war-crimes tribunal’s own investigators came to the conclusion that Karadžić had left Bosnia for Serbia on Christmas Eve 1999, crossing the Drina River border by boat after nightfall. In that case, the Clinton administration’s intensified manhunt – with all its gadgets, elite units and elaborate schemes – came too late. The prize horse had already bolted.

After Karadžić arrived in Serbia, the picaresque tale became even more bizarre. The trail went cold until 2005, when a self-styled spiritual healer and clairvoyant, Mina Minic, answered a ring on his doorbell in Belgrade to find himself face-to-face with a tall man with a long bushy beard, abundant white hair done up in a top-knot tied with a black ribbon. He looked “like a monk who had done something wrong with a nun,” Minic would recall later.

It was Karadžić, trying out a new identity provided by sympathisers in Serbian intelligence. He introduced himself as Dragan Dabic, a therapist who had just returned home from a stint in New York following an ugly split with his wife. Regrettably, she had refused to forward his professional credentials. Dabic was eager to learn the ways of a Balkan seer, including the use of a visak, a pendulum that is supposed to identify disturbances in the energy field around sick or troubled patients.

Dabic soon acquired his own visak, and his career as a mystic healer blossomed. He adopted the un-Serb middle name of David and used it increasingly as a professional moniker. He also set up a website called Psy Help Energy which advertised the David Wellbeing Programme.

He got involved in a project with a Belgrade sexologist aimed at rejuvenating the sperm of infertile men

Among other services available were acupuncture, homeopathy, “quantum medicine” and traditional cures. He also sold necklaces he called Velbing (well-being): lucky charms that he claimed offered health benefits and “personal protection” against “harmful radiation”. Karadžić had studied psychiatry in Sarajevo and had dabbled in the softer end of therapy. In the 1970s for a while he served as the in-house psychiatrist to the city’s multi-ethnic football team, with the optimistic goal of instilling in the struggling side a will to win, and later played the same role for Red Star Belgrade. The Sarajevo players remembered him making them lie on the floor in a darkened room while he played taped music and told them to imagine themselves as bumblebees flying from flower to flower. To create Dabic, he took this experience and embellished it with New Age concept of the “life force “the life force”, “vital energies”, and “personal auras.” In his spare time, he got involved in a joint project with a well-known Belgrade sexologist aimed at rejuvenating the sperm of infertile men. It was claimed that sluggish sperm would start moving faster if Dabic placed his hands in their vicinity.

He lived in one of the high-rise apartment blocks that lined Yuri Gagarin Street, named in honour of the first man in space, in the shabby remains of the concrete Socialist dream that was New Belgrade. The local kids called him Santa Claus, the kindly old man who would stop and talk to them on the way to the corner grocery store. One of Dabic’s neighbours, who had a flat across the stairwell from him, was a woman who worked for Interpol and whose job it was coordinate the hunt for international fugitives such as Karadžić.

Karadžić (left), while living as Dragan Dabic. Photograph: STR/AFP/Getty Images

As his confidence in the disguise grew, he became ever more daring. He emerged as something of a star on the Serbian alternative medicine circuit, publishing a regular column in Healthy Living magazine, and securing a franchise to represent a US vitamin company in the region. He also started visiting his local bar, the Luda Kuca (“Madhouse”), a smoke-filled, rough-edged place that appealed to a shifting crowd of impoverished war veterans, Bosnian Serbs and Montenegrins. It served country wine,šljivovica (plum brandy), and pungent, undiluted nationalism. On the wood-panelled walls were pictures of the Serb modern nationalist pantheon, with pride of place reserved for Radovan Karadžić.

On at least one occasion he was persuaded to pick up a gusle, the single-stringed fiddle of the region, and perform an epic Serb ballad under a framed portrait of himself at the height of his power. Yet no one recognised him.

In the end, this epic feat of hiding in plain sight was brought crashing down by a slip by Karadžić’s businessman brother, Luka. Late one night in the spring of 2008, he called Dabic with a phone using an old Sim card that the war-crimes investigators had on their records as being associated with the Karadžić support network, and had passed on to the Serbian intelligence services (BIA).

In May, an investigator was dispatched to check on the recipient of the call, this strange Gandalf-like figure in New Belgrade, and the penny dropped. The investigator and his colleagues then had to ask themselves what to do next. Like the rest of the Serbia, BIA was in transition. There was a pro-western reformer in the presidency, Boris Tadić, but the parliament and many of the key posts, including the top intelligence posts, were still in the hands of nationalists. The investigators gambled their careers and, instead of going to their own bosses, took their suspicions to Tadić’s office, and kept up their surveillance. But Karadžić’s fate still hung in the balance. It was only when Tadić was able to put together a liberal coalition, three months after May parliamentary elections, that he was able to replace the BIA leadership with his own man.

By this time, Karadžić was aware he was being watched. According to his lawyer, Sveta Vujacic, the fugitive began to spot unfamiliar faces in mid-July, brushing past him on the stairwell at his apartment block or at the Luda Kuca. “He knew he was encircled,” Vujacic recalled.

On the evening of 18 July, the man known as Dragan Dabic left 267 Yuri Gagarin Street in a light-blue T-shirt and a broad-brimmed straw hat pulled low over his face. He was weighed down with baggage: a white plastic bag, a raffia shopping basket and a knapsack, all of which appeared to be full. He walked to a nearby bus stop where he was soon discreetly joined by one of his BIA trackers. They both boarded the number 73 bus bound for Belgrade’s northwestern suburbs. Dabic sat towards the front. His shadow was several seats back.

When they reached the greenbelt around the Serbian capital, a couple of patrol cars steered in front of the bus and four plainclothes policemen boarded, two in the front and two in the back. They made their way toward the middle, posing as inspectors, showing their badges and asking to see tickets. The old man in the straw hat was reaching into his pocket for his fare when he felt a policeman’s grip around his arm.

“Dr Karadžić?” the policeman asked. “No, it’s Dragan Dabic,” the man protested. “No, it’s Radovan Karadžić,” the policeman insisted.

“Are your superiors aware of what you are doing?” the man asked.

“Yes, fully,” came the reply.

The officer ordered the driver to stop the bus, and the captive was escorted onto the grass shoulder. At 9.30pm on 18 July 2008, the flamboyant fiction that had been Dragan David Dabic evaporated. In his place, the ghost of Radovan Karadžić, the former high priest of “ethnic cleansing” who had haunted the Balkans for a decade, rematerialised on a Belgrade roadside as a flustered old man, his straw hat askew, clutching a white plastic bag to his breast.

Adapted from The Butcher’s Trail by Julian Borger.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/22/the-hunt-for-radovan-karadzic-ruthless-warlord-turned-spiritual-healer

No comments:

Post a Comment