Jana Riess

RNS

April 14, 2016

Yesterday I gave a keynote speech at a Mormon Studies conference Utah Valley University, raising a number of questions about the generation that fascinates me most: the Millennials, or those Americans born in the 1980s and 1990s.

You can read news coverage of the conference here or here, but here’s a basic summary of what I was trying to get at by collating a whole lot of data. (The talk was a little Death by PowerPoint-y, I’m afraid. Way too many slides. I get overexcited.)

Here are three key takeaway points:

1. Millennials as a generation are taking longer to grow up.

The Millennial generation as a whole is departing from the traditional script of adulthood: job, marriage, children.

Here’s a slide of Pew data comparing first marriage for each of four generations: the Silent Generation, the Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Millennials. By the time members of the Silent Generation (the generation born between 1928 and 1945, who are now among the top leaders of the LDS Church) reached their early 30s, almost two-thirds of them (65%) were already married.

Every generation’s age of first marriage has dropped since then to the point where only one-quarter of Millennials (26%) are married by their early 30s.

Millennials are also delaying childbirth, having fewer children, and living at home with their parents in greater numbers than previous generations (the “Boomerang” effect).

2. Millennials value inclusion and diversity.

Diversity for Millennials isn’t just a nice thing, or something to tolerate. It’s essential. In one study of Millennials in the workplace, 83% said they were more likely to be engaged with their work in a diverse, inclusive environment. Only 60% thought they could stay engaged in an environment that was not diverse.

This attitude stems directly from their experience of a rapidly changing America. In the early 1960s, when the Silent Generation entered adulthood, 85% of the nation was white, 10% was African American, and 4% was Hispanic. Other racial categories were so small as to not even be blips on the statistical radar.

But look at our nation’s mosaic half a century later in 2010, and at Pew’s projections for 2060, when there will be no racial majority in America.

Courtesy of Pew Research Center (Pew Research Center)

So long, Caucasian hegemony. Don’t let the door hit you on the way out.

3. Mormon retention is down.

There’s an abundance of good news if you’re a Mormon leader. Mormons still have the highest rates of marriage in the United States, extremely high self-reported findings about belief in God and religious practices such as daily prayer, and low incidence of high-risk behavior.

The bad news is that retention is slipping, and younger generations appear to be leading the way.

Let’s get some context for this. Millennials are the most religiously unaffiliated of any generation in recorded US history. More than a third of them have dropped out of organized religion altogether.

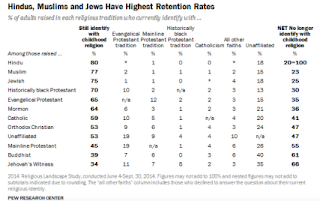

Young adult Mormons show some signs of following the national trend. When Pew surveyed this in 2014, 64% of all Latter-day Saints who were raised Mormon still self-identified as Mormon as adults.

That 64% rate is very decent, actually. It’s smack dab in the middle of the stats on religious retention in America, as you can see from the Pew table below.

But a 2007 Pew study, which asked the same questions as the 2014 one, had shown Mormon retention at 70%.

And Christian Smith’s Souls in Transition, based on research conducted in the early 2000s, had the retention rate (specifically among Mormon young adults) at 72%.

Moreover, retention rates among Mormons reportedly used to be as high as 90% in the 1970s and 1980s (though frankly those samples were small enough and that retention rate so optimistic that I’m not entirely confident we’re comparing apples to apples).

Even if we just consider the national research that has been done in the last fifteen years, Mormonism’s retention rate has been dropping, though not at the precipitous rates experienced by other groups like mainline Protestants.

If we’ve gone from a retention rate of 72 percent to 70 to 64, that’s not half bad considering the times we live in. But I doubt many LDS leaders are going to throw a Munch-n-Mingle to celebrate those numbers.

There are reasons for Mormons’ successes and failures in this area. Yesterday I tried to lay out some of the things we do wonderfully by young adults: sending them on missions; gathering them into singles wards (yes, really) where they are allowed to exercise responsibility; and simply modeling, as parents, the beliefs and behaviors we hope to inculcate. Parental influence is still, statistically, the single most influential factor in determining whether people stick with the religion of their childhood.

But there are also existing or potential problems in the ways the LDS Church is interacting with Millennials. For one thing, there has never before been such a wide generation gap between young adults and the highest leaders of the church.

It’s not just that apostles, like other people in America, are living longer than ever before. They’re also getting appointed much later in life. Recall that Thomas S. Monson was only 36 when he became an apostle. Reverse those digits and you’re getting closer to the age of appointment of our three most recent apostles (64, 62, and 60).

And of course, the church’s hard-line stance on LGBT issues is alienating to a generation that, as a whole, accepts inclusion and diversity as a way of life. The issues that previous generations have with homosexuality are not nearly as problematic for Millennials. What is problematic is the marginalization of minority groups.

http://janariess.religionnews.com/2016/04/14/mormons-20s-30s-leaving-lds-church/

RNS

April 14, 2016

Yesterday I gave a keynote speech at a Mormon Studies conference Utah Valley University, raising a number of questions about the generation that fascinates me most: the Millennials, or those Americans born in the 1980s and 1990s.

You can read news coverage of the conference here or here, but here’s a basic summary of what I was trying to get at by collating a whole lot of data. (The talk was a little Death by PowerPoint-y, I’m afraid. Way too many slides. I get overexcited.)

Here are three key takeaway points:

1. Millennials as a generation are taking longer to grow up.

The Millennial generation as a whole is departing from the traditional script of adulthood: job, marriage, children.

Here’s a slide of Pew data comparing first marriage for each of four generations: the Silent Generation, the Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Millennials. By the time members of the Silent Generation (the generation born between 1928 and 1945, who are now among the top leaders of the LDS Church) reached their early 30s, almost two-thirds of them (65%) were already married.

Every generation’s age of first marriage has dropped since then to the point where only one-quarter of Millennials (26%) are married by their early 30s.

Millennials are also delaying childbirth, having fewer children, and living at home with their parents in greater numbers than previous generations (the “Boomerang” effect).

2. Millennials value inclusion and diversity.

Diversity for Millennials isn’t just a nice thing, or something to tolerate. It’s essential. In one study of Millennials in the workplace, 83% said they were more likely to be engaged with their work in a diverse, inclusive environment. Only 60% thought they could stay engaged in an environment that was not diverse.

This attitude stems directly from their experience of a rapidly changing America. In the early 1960s, when the Silent Generation entered adulthood, 85% of the nation was white, 10% was African American, and 4% was Hispanic. Other racial categories were so small as to not even be blips on the statistical radar.

But look at our nation’s mosaic half a century later in 2010, and at Pew’s projections for 2060, when there will be no racial majority in America.

Courtesy of Pew Research Center (Pew Research Center)

So long, Caucasian hegemony. Don’t let the door hit you on the way out.

3. Mormon retention is down.

There’s an abundance of good news if you’re a Mormon leader. Mormons still have the highest rates of marriage in the United States, extremely high self-reported findings about belief in God and religious practices such as daily prayer, and low incidence of high-risk behavior.

The bad news is that retention is slipping, and younger generations appear to be leading the way.

Let’s get some context for this. Millennials are the most religiously unaffiliated of any generation in recorded US history. More than a third of them have dropped out of organized religion altogether.

Young adult Mormons show some signs of following the national trend. When Pew surveyed this in 2014, 64% of all Latter-day Saints who were raised Mormon still self-identified as Mormon as adults.

That 64% rate is very decent, actually. It’s smack dab in the middle of the stats on religious retention in America, as you can see from the Pew table below.

But a 2007 Pew study, which asked the same questions as the 2014 one, had shown Mormon retention at 70%.

And Christian Smith’s Souls in Transition, based on research conducted in the early 2000s, had the retention rate (specifically among Mormon young adults) at 72%.

Moreover, retention rates among Mormons reportedly used to be as high as 90% in the 1970s and 1980s (though frankly those samples were small enough and that retention rate so optimistic that I’m not entirely confident we’re comparing apples to apples).

Even if we just consider the national research that has been done in the last fifteen years, Mormonism’s retention rate has been dropping, though not at the precipitous rates experienced by other groups like mainline Protestants.

If we’ve gone from a retention rate of 72 percent to 70 to 64, that’s not half bad considering the times we live in. But I doubt many LDS leaders are going to throw a Munch-n-Mingle to celebrate those numbers.

There are reasons for Mormons’ successes and failures in this area. Yesterday I tried to lay out some of the things we do wonderfully by young adults: sending them on missions; gathering them into singles wards (yes, really) where they are allowed to exercise responsibility; and simply modeling, as parents, the beliefs and behaviors we hope to inculcate. Parental influence is still, statistically, the single most influential factor in determining whether people stick with the religion of their childhood.

But there are also existing or potential problems in the ways the LDS Church is interacting with Millennials. For one thing, there has never before been such a wide generation gap between young adults and the highest leaders of the church.

It’s not just that apostles, like other people in America, are living longer than ever before. They’re also getting appointed much later in life. Recall that Thomas S. Monson was only 36 when he became an apostle. Reverse those digits and you’re getting closer to the age of appointment of our three most recent apostles (64, 62, and 60).

And of course, the church’s hard-line stance on LGBT issues is alienating to a generation that, as a whole, accepts inclusion and diversity as a way of life. The issues that previous generations have with homosexuality are not nearly as problematic for Millennials. What is problematic is the marginalization of minority groups.

http://janariess.religionnews.com/2016/04/14/mormons-20s-30s-leaving-lds-church/

No comments:

Post a Comment