https://youtu.be/pywIJdvJe7I?si=AGNojmsEaUQjkEQX

Mar 6, 2024

Sex cult leader Eligio Bishop sentenced to life

https://youtu.be/pywIJdvJe7I?si=AGNojmsEaUQjkEQX

Oct 23, 2023

SHAKAHOLA: How Paul Mackenzie was inspired by Australian cultists

Nation

October 23, 2023

An Australian cult linked to controversial preacher Paul Mackenzie had been taken to task over questionable kidney donations, according to reports seen by the Nation.

Mr Mackenzie and his wife, who are leaders of the "Jesus Christians" group, have been accused by a Senate committee of inciting religious extremism in the country that led to the deaths of over 400 people in Shakahola, Kilifi County.

An independent search by the Nation established that Dave and Sherry Mackay had been accused of brainwashing their believers into donating their kidneys to complete strangers under suspicious circumstances.

They also drained their followers' bank accounts and separated them from their families.

The Senate ad hoc committee that is investigating the Shakahola deaths and is chaired by Tana River Senator Danson Mungatana mentioned the Mackays in its report, claiming that Mr Mackenzie was indoctrinated by their teachings.

According to the committee, Mr Mackenzie used virtual links and social media to reach out to the foreigners and their cult dubbed,"Voice in The Desert".

Furthermore, it is alleged that he hosted their associate in Makongeni, Nairobi City County, who delivered anti-government [sermons], particularly stating that the Huduma Namba was "the mark of the beast".

Additionally, the associate allegedly urged followers to abandon earthly possessions and follow Mr Mackenzie to the "promised land", which was later established to be located in Malindi.

Reports show that, in the early 2000s, the Mackays and their followers hit headlines across Australia and the UK over questionable organ donations, particularly kidneys.

According to media reports at the time, the group's members from Kenya, Britain, the US and Australia had donated their kidneys as part of their desire to "live selflessly", following teachings by the cult. These occurrences led the group to be referred to as the "kidney cult".

The believers donated their organs secretly as their kin, who were interviewed by journalists, said they suspected that they had been brainwashed.

"Information [made available] to the committee established that Paul Mackenzie was influenced by Dave Mackay and Sherry Mackay from Australia, who are founders of a cult movement known as Voice in the Desert. The teachings of this cult include forsaking all private ownership of property, surrendering earthly possessions and relocating to an isolated communal place where members serve one master," the committee report states.

In May this year, documents filed at the Milimani Law Courts in Nairobi indicated that some of the Shakahola victims may have had their organs harvested before they were buried in mass graves.

The documents filed by Chief Inspector Martin Munene, in an application seeking to freeze bank accounts belonging to New Life Centre and Church leader Ezekiel Odero, who was linked by detectives to Mr Mackenzie, alluded to a wide network of organ traffickers in the country that is under investigation.

"Post-mortem reports have established missing organs in some of the bodies of the victims so far exhumed. It is believed that trade on human body organs has been well-coordinated involving several players," said the officer.

Associates of the two Australian preachers had also been accused of kidnap across different countries, including Kenya and the UK.

In Kenya, records show that Roland and Susan Gianstefani, who are members of the "Jesus Christians", were arrested in 2005 over the disappearance of a woman and her seven-year-old son.

The church later released a video of the woman and her son on their website and YouTube channel, with the woman defending the two suspects while claiming that she was in hiding from her father who wanted to take custody of her son. It later emerged that Roland and Susan had encountered a similar case in the UK in 2000 when a British judge handed them suspended six-month jail sentences for refusing to reveal the whereabouts of a teenage boy who had left home to join their group.

In their report, the Senate committee expressed frustrations in their bid to expose the truth about the Shakahola massacre.

They accused Interior Cabinet Secretary Kithure Kindiki and his Health counterpart Susan Nakhumicha of blocking government representatives summoned to appear before the committee from testifying.

"Despite extending invitations and issuing summonses, the committee was unable to procure the attendance of key witnesses. These included former Kilifi County Security Committee members, who were transferred following the discovery of the tragedy in Shakahola forest," the report reads in part.

Prof Kindiki informed the committee that some of the transferred officers were witnesses and others suspects in the ongoing investigations.

The committee recommended that "the Attorney-General declares Mackenzie's Good News International Ministries a society dangerous to the good government of the Republic of Kenya pursuant to section 4 (1) (ii) of the Societies Act (Cap 108) within thirty (30) days of adoption of the report by the Senate."

It also accused the country's justice and security systems of failing to take appropriate action early enough despite the matter having been extensively publicised in the media and by human rights organisations, victims' families and political leaders.

- Additional reporting by Farhiya Hussein

Oct 21, 2023

Report reveals how Makenzi's deceptive tactics lured followers

Standard

October 20, 2023

A Senate report has accused Paul Makenzi of being the mastermind of the Shakkahola massacre and recommended he be charged for the death of at least 429 people.

The report by the Tana River Senator Danson Mungatana-led committee ad hoc committee has revealed how Makenzi lured hundreds of gullible followers to their deaths, including killing those who defied his starvation orders.

The team established that Makenzi intensified his recruitment during the uncertainty and anxiety occasioned by the Covid-19 pandemic.He recruited hundreds of vulnerable people through agents in different parts of the country who systematically lured followers to their deaths through deceptive recruitment tactics, states the report.

The report released yesterday claims that Makenzi manipulated his followers by promising them land in Shakahola. Firstly, it says, he financially exploited them by requiring them to sell their assets and hand over the proceeds to him.

The committee established that Makenzi systematically concealed properties and money that he fraudulently and unlawfully acquired from his victims.

Other than using the agents, the report states that Makenzi also lured people to the forest through preaching, using a variety of media channels to disseminate his harmful doctrines, including social media platforms such as YouTube.

"He used virtual links and social media to foster foreign links with "Voice in the Desert", an Australian cult founded by Dave and Sherry Mackay and hosted their associate in Makongeni area, Nairobi County, who delivered summons echoing anti-government sentiments, particularly stating that Huduma Namba was "the mark of the beast", It states.

"He intentionally isolated his followers by moving into Shakahola Forest, a remote and inaccessible area with no access to social services, and caused his followers to cut links with family members, thus leaving them dependent and without protection. He strategically and systematically targeted and isolated extended families, and as a result of his atrocious actions, entire families perished, leaving relatives devastated. In some instances, entire lineages were wiped out," it says.

Inside the over 800-acre Shakahola forest, Makenzi established an armed gangthat violently enforced his starvation doctrine by attacking and killing followers who changed their minds about willingly starving themselves to death.

But the "deserters", according to the report, were first arraigned before a makeshift court where mock trials were conducted and were sentenced.

"He set up a makeshift court where he held mock trials of followers who had refused to comply with starvation orders. The orders from this makeshift court would be enforced by the armed gang," states the report

The Mungatana-led committee established that Makenzi exploited the vulnerability and subjected children to painful and slow death by starvation;

The children were denied access to health care, basic education, basic nutrition, shelter, and the right to be protected from abuse and neglect in clear violation of Article 53 of the Constitution of Kenya, the Children's Act, 2022, and the Basic Education Act, 2013, states the report.

"While his followers faced a slow and painful death through starvation, Makenzi and his gang of violent enforcers enjoyed elaborate meals as evidenced by menus and cooking apparatus found at his house in Shakahola Forest," it says.

Makenzi was first linked to the death of his followers in March this year after he was arrested on allegations of the murder of two children who had succumbed to starvation and suffocation.

Following arraignment in court, Makenzi was granted bail of Sh10,000 by a Malindi Magistrate's Court.

But the Mungatana committee reports that after he left protective custody, Makenzi intensified the starvation orders that caused the deaths and concealment of hundreds of bodies of his deceased followers.

"As part of concealing the mass graves where his followers had been buried, Makenzi planted vegetables on the graves," states the findings of the report.

It adds; "After his arrest without any iota of remorse and in full knowledge of the impact of his heinous acts further intimidated the public in his now infamous brazen remark, "kitawaramba" loosely translated to mean "it will catch up with you".

During the rescue process by security agencies, some of the survivors were found locked in their houses emaciated and frail, naked and their legs and hands tied with either turbans or ropes.

But the committee now claims that Makenzi also buried victims who were still living but near death as a result of starvation to terminate their lives.

"Acting in concert with his goons, savagely and sadistically forced starvation of his followers. He radicalized and indoctrinated his followers, causing them long-term psychological, physical, and emotional harm which will require long-term care and rehabilitation," said the report.

It concludes that Makenzi's gruesome actions caused a long-term negative social, cultural, ecological, and environmental impact on the local community in the Shakahola area.

https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:xta4-Vg8nKwJ:https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/national/article/2001483828/report-reveals-how-makenzis-deceptive-tactics-lured-followers&hl=en&gl=us

Oct 9, 2023

State relies on terror law to detain cult leader Mackenzie, followers for up to a year

October 09, 2023

Brian Ocharo

Kilifi cult leader Paul Mackenzie and his associates could be detained without charge for up to a year, court documents show.

The state has invoked the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA), which allows for up to 360 days of extended detention without charge.

Prosecutors have reviewed updated police files on the Shakahola massacre investigation and concluded that it is necessary to continue detaining Mackenzie and his associates.

Documents filed in the Shanzu court show that the prosecution, investigators and the government chemist all agree that the suspects need to be detained for longer to allow investigations to be completed before formal charges are laid.

"The prosecution has reviewed the updated police files, consulted with other agencies involved in the investigation and independently concluded that further detention is necessary and justified," the document states.

The State also argues that charging Mackenzie and his associates with the mass murder in the Shakahola forest would be contrary to the object and purpose of section 50(9) of the Constitution, as enabled by the Victims Protection Act.

In addition, the State maintains that continued detention will ensure a fair and expeditious trial, rather than triggering the trial process prematurely and then asking the courts for more time to complete the investigation.

The investigation into the Shakahola massacre has proven to be complex, arduous, costly and constantly evolving as investigators gradually build on the known facts and work to unravel the unknowns.

In addition, there are new factors that have had a direct impact on the turnaround time for securing critical material evidence, such as badly decomposed bodies that make it difficult to determine the cause of death, and a limited number of reference samples from biological relatives that negatively affect the identification and linking of the deceased with their families.

It has been argued in court that the identification of the victims is crucial for charging decisions, given the different causes of death.

Therefore, the State argues that an additional period of at least six months, as requested, is necessary to ensure the outcome of the scientifically based victim identification process.

"The ongoing investigation is necessary to fill gaps in the evidence and to ensure fair charging decisions. Correct and complete charges will facilitate effective case presentation and management by the courts, thereby expediting the trial process," said Chief Inspector Raphael Wanjohi, who is leading the investigation.

According to data presented in court, 214 people died of starvation, 39 of suffocation, 14 of head injuries, while the cause of death of 115 people remains unknown.

The prosecution has applied for a six-month extension of Mackenzie's and his associates' detention, citing the circumstances of the Shakahola massacre as justification for the maximum period of detention without charge.

"The overwhelming evidence before this court demonstrates that POTA is aimed at crimes such as the Shakahola massacre, where sectarian, Christian-oriented, faith-based violent extremism reveals radicalisation contrary to section 12D of POTA," Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions Jamie Yamina said in court papers.

Although it may appear that Mackenzie and his followers have been detained for an extended period of time, the state has additional time under POTA to extend their detention in order to complete the investigation.

The state has argued that the extension is necessary to prevent the suspects from harming themselves due to their indoctrinated minds and extreme beliefs.

For the first group, comprising Mackenzie and 17 others, the State has 223 days left to continue detention, out of a possible maximum of 360 days from the date of their initial detention, pending the completion of investigations.

In the second group, consisting of Charles Charo alias Musa Suleiman and 10 others, the State has 253 days left to lawfully detain them out of a maximum of 360 days. In the last group, which includes only Alex Mnangwe Odari alias Alex wa Galilaya, the State has 283 days of detention pending completion of investigations.

The State argues that there is no legal obstacle or justification to prevent it from taking this course of action, notwithstanding the discomfort of Mackenzie and his associates.

The State argues that the Shakahola case has prompted interventions aimed at possible policy and legislative reforms. Until these reforms are in place, all evidence must be preserved, not only for the trial, but also in the interests of public safety and national security.

"Until social investigation reports demonstrate the existence of safer alternatives, a prison or detention facility remains the least restrictive measure available to achieve the intended purposes," the prosecutor said.

The State also said it had established that Mackenzie and his associates were indoctrinated or radicalised individuals who required close supervision, care and control.

The Shakahola deaths suspects are due to appear in court later this week.

bocharo@ke.nationmedia.com

Sep 28, 2023

In Tragedy's Wake, Kenya Grapples With How To Combat Dangerous Cults

Over 400 died in the recent Shakahola Massacre, but regulating the world of American-inspired Pentecostal pastors is far from straightforward

New Lines Magazine

Elle Hardy

Elle Hardy is a journalist and the author of “Beyond Belief: How Pentecostal Christianity Is Taking Over the World”

September 28, 2023

In late June, Joseph Juma Buyuka died after a 10-day hunger strike at Kenya’s Shimo La Tewa Prison. No ordinary prisoner of conscience, Buyuka had been detained along with 64 fellow followers of the radical preacher Paul Nthenge Mackenzie, leader of Good News International Ministries, the doomsday cult behind over 400 confirmed deaths in what has become known as the Shakahola Massacre.

Buyuka was reportedly one of Mackenzie’s key lieutenants while they lived in the Shakahola Forest, a secluded area north of the coastal Kenyan city of Mombasa. In one of the worst peacetime death tolls in modern African history, officials estimate that at least 800 victims starved themselves to death — with some of the 427 exhumed bodies showing signs of murder.

Authorities moved in on the rural encampment in April, after elders in nearby villages reported emaciated children arriving and begging for food, as wretched skeletal bodies began overwhelming the local morgue. Under Mackenzie’s spell, Shakahola victims, largely impoverished young people and desperate young families, had undergone a regime of extreme fasting in an attempt to hasten a meeting with Jesus.

Reportedly already too weak to walk when he was first arraigned at court, Buyuka and 64 others were being investigated for, among other things, murder and manslaughter, attempted suicide, religious radicalization and cruelty and neglect toward children.

The Shakahola Massacre is possibly the worst cult mass suicide since Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple saw 900 followers perish at “Jonestown” in Guyana in 1978. Both Jones and Mackenzie appear to have been inspired by the same obscure American preacher who died in the 1960s. An unalloyed tragedy in its own right, the events have many in Kenya as well as the wider African continent questioning the influence of rogue and radical preachers — and those from farther afield who have inspired them.

Mackenzie, who has denied culpability in the massacre, comes from the most extreme end of the evangelical Pentecostal-charismatic movement. In 2020, the World Christian Encyclopedia counted 644 million Pentecostals and charismatics worldwide, with 230 million of those on the African continent. One of the key factors in the rise of the movement, centered on the role of the Holy Spirit, is that it has no denominational hierarchy to provide oversight and vetting of pastors.

In the Pentecostal tradition, the only thing that pastors need to hold serious moral and spiritual authority is followers. The most charismatic, in both senses of the word, tend to rise to the top. On the one hand, this is a blessing, providing a more culturally and materially accessible form of faith to the developing world. But equally, this unfettered way of “doing church” has resulted in a new generation of extremist preachers.

Though undoubtedly a horrific outlier of Pentecostalism, Mackenzie is a self-taught pastor whose force of personality turned him into perhaps this century’s most prolific cult leader — and, as Buyuka’s recent death shows, one who still has a powerful hold over his followers from behind bars.

As authorities work their way through the bodies, the massacre is prompting serious questions about whether religious leaders ought to be subject to regulation and just where the boundaries of church and state lie. Kenya’s President William Ruto, himself an evangelical, launched a task force to look into enacting new laws to crack down on rogue churches and pastors, which led to the National Council of Churches fearing an attack on their religious freedom.

Weeks after the initial discovery of bodies in April, survivors were being found hiding under bushes, still refusing food and water. At the rescue center that housed them, many continued to deny themselves sustenance. It was then that the authorities charged “the 65” with attempted suicide — a misdemeanor punishable by two years’ imprisonment — and attempted to force-feed them.

In an August court appearance, Mackenzie held firm, telling journalists that those who want to see Jesus have to undergo trials while on earth.

“Go read John 12, which states that don’t be afraid of what befalls you,” he said. “However, be patient. This is in accordance with the preachings of Jesus Christ.” The only earthly sin he had committed, Mackenzie claimed, was eating — and the moment he stopped eating, he too would join his heavenly father. Mackenzie’s lawyer Wycliffe Makasembo stepped in to stop him from speaking further, advising journalists to not “quote any sentiments that my client has made, apart from Bible verses that he has mentioned.”

Out on Shakahola’s 800 acres of ochre fields, where authorities and families are still sifting through mounds of upturned dirt for remains, Mackenzie’s biblical justifications are of little concern.

A pathologist working on the case said that the victims’ remains showed signs of extreme starvation. Some appeared to have been murdered, with signs of smothering and blunt force trauma. Investigators say that autopsies have raised suspicions of organ harvesting among the deceased, while Kenya’s Interior Cabinet Secretary Kithure Kindiki said there are fears that some of the scores of dead children may have been victims of sexual abuse.

An estimated 400 followers remain missing. Many of them had moved to the forest from around the country and, in a few cases, internationally, lured by Mackenzie’s radical online preaching. Their families’ trauma has been compounded by the incapacity of regional authorities to process the sheer number of bodies. Complex and lengthy identification processes, such as DNA testing, are placing a burden on relatives, most of whom have limited resources and need to travel to the remote region to give samples.

In the beginning, one former congregant told a local reporter, Mackenzie’s sermons “were normal,” but from 2010 “his ‘End Times’ messages began.” It is unclear precisely what led to Mackenzie’s radicalization during this period but he found many followers willing to move with him in that direction. Directed to retreat from the world to prepare for the end of days, Mackenzie’s ministry pulled children out of school, entering followers into church-arranged marriages and disconnecting them from their communities.

Julius M. Gathogo, a theology professor at Kenyatta University, told New Lines that although Mackenzie had a stint as a televangelist, he was “virtually unknown” to most Kenyans before the Shakahola massacre came to light. Before founding his Good News International Ministry in 2003, Mackenzie had worked as a nighttime taxi driver in the capital of Nairobi.

During this time, Gathogo said, Mackenzie was “arrested four times for his controversial sermons, but acquitted after every time due to lack of evidence.” In one such incident in October 2017, police rescued 93 children from his care and the preacher was charged with promoting radicalization. “The pastor has brainwashed residents” against schools and hospitals, one local official later told reporters, explaining that Mackenzie was teaching children an extreme form of Christianity in an unregistered church school. But again, Mackenzie was acquitted. A year later, residents in a town near the massacre site demolished one of his churches, protesting what they decried as false Christian teachings.

Mackenzie’s increasingly public pronouncements saw him lock horns with a prominent local member of Parliament in the region of Malindi, Aisha Jumwa, now the government’s secretary of public service and gender. Jumwa denounced the teachings that saw children leaving their allegedly “satanic” education and accused Mackenzie of bribing security agencies to turn a blind eye to his bizarre activities.

“It is absurd that despite having been arrested about three times and charged,” she said at the time during a public rally, “the pastor is still scot-free and continues with his work of radicalizing schoolchildren.”

Mackenzie, who preaches rejection of secular institutions, nevertheless replied that critics needed to go to court. “I am not afraid to serve my God,” he said. In spite of the legal system’s insistence of a lack of evidence, damning indictments of Mackenzie’s preaching continued to emerge in public forums. One video surfaced on social media showing children aged 6 to 17 renouncing their secular education, declaring it ungodly.

In 2019, the preacher was again arrested for inciting his congregants against the new government identity card, called the “huduma namba” (service number). “Mackenzie called it satanic and likened it to the number of the beast, seen in the Book of Revelation,” Gathogo said. By getting involved in a significant national issue, Gathogo said that Mackenzie “publicized himself for the wrong reasons.”

If the huduma namba helped bring Mackenzie to prominence, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have accelerated his doomsday message and further radicalized his followers. For many among them, it was confirmation that the world was coming to an end and that Mackenzie was the prophet of the End Times. More and more followers began to quit their jobs and move to the forest, where some bought plots of land for $80 — about the price of a sheep, though the land was probably worth around 40 times this — in sections with names such as Galilee and Bethlehem.

Another act of God appeared to be the final death knell for many in the community. One victim, whose husband had bought a small plot of land and moved the family to the massacre site in 2020, said that they used to eat and drink but things changed when drought set in. Since October 2020, season after season of failed rains in East Africa have created the worst drought in 40 years. Mackenzie began telling his followers that they needed to “fast to meet Jesus.”

Though Mackenzie’s was clearly a fringe group, Kenya has proven fertile ground for new religious movements, many of which have emerged from Pentecostalism. In one of the most devout countries on earth, more than 85% of Kenyans identify as Christian. In the 21st century, Gathogo explained, the Afro-Pentecostal movement has become one of the dominant religious movements in the country — with about one-third of the population, or some 15 to 20 million people, adhering to it. In order to keep up, Gathogo notes, more traditional denominations such as Catholicism and Anglicanism are engaging in Pentecostal-style practices, such as faith healing and speaking in tongues.

“The British colonial government did not encourage Pentecostalism before 1963 when colonialism ended,” Gathogo said, which helps explain the first wave of the movement as something more localized and authentic. A key part of the appeal of this strand of evangelical faith is “its ability to easily resonate with indigenous cultures,” he added.

“This is in terms of their vibrant modes of worship,” Gathogo said, “their noisiness, their forms of hospitality appear to reach the lowest in society.” Pointing to the singing and dancing that gets worshippers inside the tent, he noted that these are part of indigenous African religiosity. “Hence, postcolonial Africa has to dance with the rhythms of Pentecostalism, which are influential across the social-religious divides.”

Here, the lines between church and state are often blurred. At political rallies, Gathogo said, it is common to see performances from Pentecostal gospel artists. They are “influencing political events” by putting on a good show and appealing to the deep Christian beliefs, flecked with African spirituality, that flow through the country.

In this regard, Good News International was very much a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

“Paul Mackenzie’s religio-cultic outfit initially poses as an African Pentecostal church, that displays communality, hospitality and care for the lowly and needy in society, and vibrant drama-dancing-singing outfits,” Gathogo said. Looking like other African-Pentecostal churches, “Mackenzie’s Good News International Ministries impresses you with evangelical faith that takes the Bible seriously and believes in Jesus Christ as savior and lord.”

Kapya John Kaoma, an expert on U.S. influence in East African churches, told New Lines that the second wave of American evangelical missionaries in the 2000s made a significant contribution to faith in the region. U.S.-funded groups opened schools and imported Christian television. Through this, both local and international fundamentalists found opportunities to set up shop in places where the regulation of education was weak.

One particular offshoot of Pentecostalism, the American-founded New Apostolic Reformation, “dumped” traditional pastors “in favor of this new group of people who felt they were neglected by the demands of the academy,” Kaoma said. Disreputable institutions offered theology doctorates “within three months.”

The new breed of pastors began pulling members away from mainline Christian denominations. “They are highly focused on the people who are in need of help, those who are economically disadvantaged, those who are sick or unemployed,” he said. Their particular pulling power was healing and miracles. “As long as you’re charismatic enough, you are able to control a group of people,” Kaoma added, “and whatever you tell them to do, they do.”

In the George W. Bush era, hardcore American evangelical groups were encouraged to push their ideology on USAID-funded programs in Africa. Kaoma said that, in turn, these groups began to “monopolize” print media, radio and, eventually, television. Mainstream Pentecostal churches began using American talking points, including vehemently anti-LGBT and anti-abortion views, opening the door for extremist preachers such as Mackenzie to push ever more radical ideas.

While indigenous African churches had their own theology, which wasn’t necessarily opposed to these outside views, many local leaders, who had historically focused on healing, were invigorated by taking on “the modernity of the American Christian right, which they could watch on television,” Kaoma said. The prosperity gospel, that most American of ideas, also became a powerful force.

Pastoral networks, not to mention sympathetic political figures, benefited greatly from this “health and wealth” brand of Christianity. As the saying goes, if a preacher can name it, he can claim it. Kaoma added that among many Christians in Africa, word from the West is highly revered. “Anything that is associated with whiteness in Africa has legitimacy,” he said. “When Mackenzie is reading a book or citing something written by a white person, that has power.”

This may help to explain why investigators believe that Mackenzie’s radical turn came about when he became a devotee of William Branham, an American doomsday preacher prominent in the 1940s and ’50s who, until Shakahola, was most notable for influencing Jim Jones.

Branham emerged from a small postwar movement called the New Order of the Latter Rain, which took on the established Pentecostal authority, itself not even 50 years old at the time. Latter Rain leaders wanted to practice the powers gifted by the Holy Spirit to Jesus’ disciples — such as casting out demons, healing the sick and raising the dead — and, critically, they wanted to do it on demand rather than waiting for these gifts to be bestowed upon them.

The effect of Latter Rain on present-day Christianity cannot be understated, with direct descendants of the movement influential on many events, including the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, and on prominent Brazilian and Korean megapreachers, among other personalities. Those influenced include mass murderers, such as Mackenzie. Though Branham is rejected by the vast majority of the Latter Rain movement’s modern-day disciples and is not a popular figure in Kenya, according to Gathogo, his works managed to captivate this small group as it moved toward the most tragic of ends.

Called “the Message,” Branham’s sermons and books were churned out from his Indiana headquarters and distributed globally. He adopted a doctrine central to early Latter Rain preachers called “atomic power,” which could be achieved through 40 days of fasting and prayer. In one 1961 revival sermon, Branham conceded that some of his followers had put their lives in danger from the extreme practice. Pregnant women, he said, “lose their mind” and “go into insane institutions from that.”

In an interview with New Lines, Douglas Weaver, a religious studies professor at Baylor University, said that Branham was a leading divine healer in the United States in the 1940s and ’50s who also launched “crusades” overseas. Branham began calling himself “the second John the Baptist,” after the prophet who foreshadowed Christ, and predicting the second coming, which saw him become a favorite of doomsday preachers. The rogue preacher had so many “nutty doctrines,” Weaver said, that by the 1960s, Pentecostals in the U.S. began to shy away from him. Yet the fact that Branham’s ministry has continued to hold sway is an example of how some fundamentalist publications “are considered to be infallible interpretations of the Bible.”

Weaver said that anybody who reads Branham and “wants to be what I would call an authoritarian prophet” can appeal to the preacher’s legacy and say that God continues to speak through them as we reach the End Times. In a 1965 sermon shortly before his death in a car accident, Branham delivered a sermon in which he warned listeners that “no one wants to die” but that some among them would have to “die in martyrdom.”

Though Branham was “eccentric,” Weaver said, his sermons were variations of the idea that “we’re in the end days and you need to have a prophet.” Followers see him as an “infallible authority” who talks about the end, with generic prophecies about wars and other apocalyptic events. “He made pronouncements that people are simply supposed to follow,” Weaver said, “so it could become cultic.” Chief among them was that, if you believed his message, you would be raptured: that is, transported from Earth to heaven on the second coming of Christ. “You can take Branham’s theology and go as far off the deep end as you want,” Weaver added.

In Kenya and well beyond its borders, esoteric belief systems and new religious movements emerging from Pentecostal thought highlight the movement’s lack of institutional oversight. The advent of social media also offers perverse incentives. Kenya is “awash with online recruitments where targets are incentivized to go to the extreme,” Gathogo said. Believers are enticed with “promises for a better life, for a job” and told that they may find a spouse.

Gathogo explained that, in East and Central Africa, “failure to offer sound theological training” and “poor vetting in Afro-Pentecostal leadership” have seen warlords and drug runners like Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army establish theocratic enclaves with extremist beliefs. Unscrupulous pastors are offering “breakthroughs in all dimensions of life,” Gathogo said, including visas for overseas work, or offering exhausted mothers ways to get their teenagers to behave. “A church where the founder cannot be disciplined by a higher authority or by established structures,” he said, “cannot be trusted.” After all, “we are all sinned and fallen short of God’s glory.”

There exists a spiritual marketplace of people seeking solace and support in pastors who offer solutions. Preachers like Mackenzie “take advantage of that,” Kaoma said. Any success becomes the leader’s success. Once followers find work, or love, they will often attribute that to the church, and donate money in kind, oiling the wheels of the pastor.

What is unusual in the case of the Shakahola Massacre, Kaoma noted, is that preachers like Mackenzie tend to hold the most sway in urban areas, where cost-of-living pressures and isolation from traditional communities are common. In rural areas, African-initiated religious movements, which are tied to health and community, are usually much more persuasive. The fact that Mackenzie took many followers with urban concerns and moved them to isolation in the forest, where they became willing to die for their newfound beliefs, might have contributed to the deadly success of his movement.

In this blurring of urban and rural religious divides, Mackenzie’s movement is far from alone. Shakahola is the latest and most high-profile example of extreme African Pentecostal movements in rural communities exercising undue influence over their parishioners. In 2014, South African “professor” Lesego Daniel encouraged his congregation to drink poisonous chemicals as a form of communion, claiming that he had the gift of turning “petrol into pineapple.” Two years later, his protege, pastor Lethebo Rabalago, gained infamy as the “Prophet of Doom” after he was found guilty of assault for spraying churchgoers with Doom-brand insecticide to help cast out demons that presented in the form of AIDS. Earlier this year, a Ghanaian pastor ordered church members to strip naked so that the Holy Spirit could move freely through them.

The rise of extremist preachers spanning the continent has amplified the voices of some religious leaders. In Rwanda, President Paul Kagame championed a law that recently came into effect requiring pastors to have a theology degree before they can start their own congregations. It is said to have resulted in the closure of some 6,000 churches.

In the wake of Shakahola, Kenya’s President Ruto launched a task force to review the legal and regulatory framework governing religious organizations, asking the public to submit their proposal on changes required to curtail religious extremist organizations. The 17-member committee is currently reviewing the public submissions. “The operation on criminals hiding behind religion is not a war against any faith or institution,” Kindiki, the interior secretary, said at its establishment. “Crime knows no religion.”

The task force’s key responsibilities are identifying gaps that have allowed extremist religious organizations to set up shop in Kenya, as well as putting together a legal framework that prevents radical religious groups from operating in the country. This could include education standards for pastors — going against the grain of churches and movements emerging from Pentecostalism, which have traditionally flourished in poor communities where formal training can be hard to come by.

“As far as I’m concerned, it is necessary,” Gathogo said. Yet for some, the government drawing the line on what can and can’t be preached is a fraught development. Opponents of new regulations say that “churches should be left to reveal themselves,” he added. Others have argued that the massacre was a one-off affair and that the state should have intervened in the case earlier but that, in general, churches should be left to self-regulate in order to gain communities’ respect.

Reconciling deeply spiritual matters with political concerns is difficult in a country so steeped in faith. Many argue that the separation of church and state is a colonial idea that doesn’t reflect the values of a modern African state. There is also the very real chance that “outlawed” preachers would attract followings by virtue of being subversive.

Those arguing for regulation, such as Gathogo, are urging Parliament to take their time on consulting and drafting an appropriate law, as rushing will see it fail in both the court of public opinion and the supreme court, where there is a risk that it will be deemed unconstitutional.

But no matter what laws are brought into place, whether they can effectively come to grips with a changing culture of faith is another issue entirely. Gathogo noted that Mackenzie is representative of the rise of new religious movements in 21st-century Africa.

“They interpret the Bible from an extremist position, and even avoid theological training, as they claim that the Holy Spirit is sufficient trainer,” he said. “They reject decency and eventually end up as con artists.”

Among this strain of preachers, “The leader is elevated to a deity, his word is law, and people are psyched to fear him,” he added.

If successful, Kenya’s laws may be looked at around the world as a way of reining in rogue operators, but they open up a legal and ethical minefield, not to mention the risk of turning pastors such as Mackenzie into martyrs.

For Gathogo, bringing in new standards for religious leaders speaks to broader issues of governance on the continent, where preachers are stepping in to fill the void left by states unable to meet people’s material needs, let alone their spiritual ones.

“Africa does not need strong men,” Gathogo said, “but strong institutions.”

Aug 31, 2023

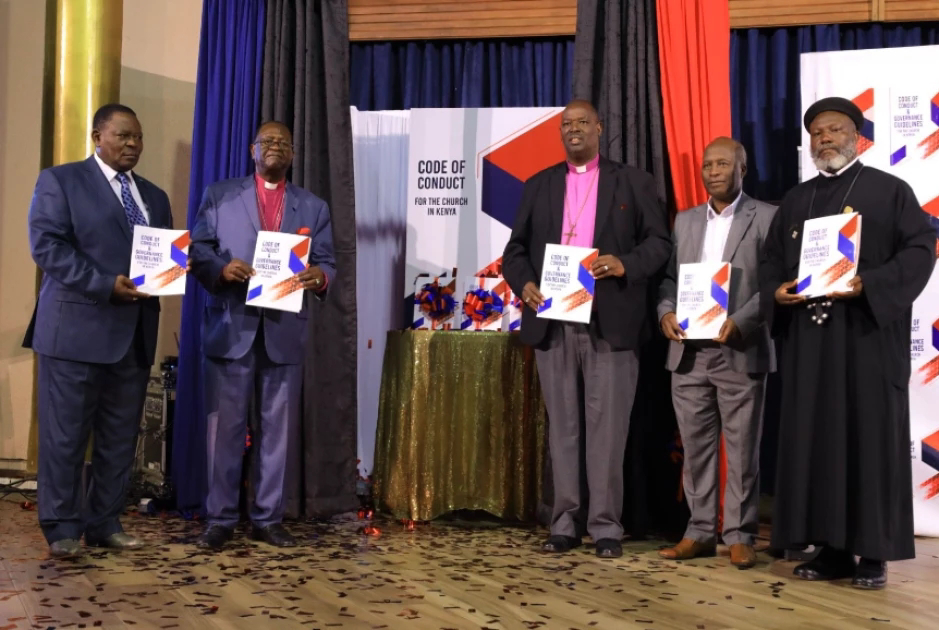

Church Leaders Roll Out Code of Conduct to Put Rogue Preachers in Check

Churches have moved to self-regulate as the government undertakes a crackdown against rogue preachers and institutions in the country following the Shakahola massacre that has so far claimed 429 lives.

Religious leaders, lawyers and human rights groups led by Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) Chairman Bishop Emeritus David Oginde on Wednesday launched the Code of Conduct and Governance Guidelines for the Church in Kenya, in a bid to counter impending State imposed regulations on religious institutions.

A 12-member steering committee chaired by Bishop Oginde drafted the rules in a move by the churches to self-regulate, as the government tightens the noose on rogue preachers in the country.

"The danger of where we are now is that if we get now, not rogue pastors, but rogue leaders, they could just say no more preaching; and it can happen," said Bishop Oginde.

Anglican Church Archbishop Rev. Jackson Ole Sapit, on his part, stated: "Let the congregants hold their leaders accountable. When they see me doing the contrary, let them stand up and say 'that is not right, we will not agree, and we will not allow you to do that.'"

The guiding principles and values contained in the Code of Conduct indicate the following;

1. Integrity and ethical conduct are central to Biblical teaching and practice.

2. The church shall promote and enhance the wellbeing of the brethren and of society as a whole in accordance with Christian beliefs and convictions, and refrain from any conduct that undermines the constructive role that churches play in the society.

3. The church shall respect, protect and preserve life and shall refrain from any conduct that devalues, dehumanizes or destroys life.

4. The church shall endeavour to uphold the sanctity of life.

5. The church individually and collectively, shall respect and uphold the dignity of every person and shall not abuse or exploit any person, or do anything to violate or degrade that person.

6. The church values children, born and unborn, and shall act in their best interest when under their care by protecting them.

7. The church shall respect the right of every person to join any faith or religion of other choice without bullying, harassment, intimidation or victimization.

Senior Counsel Charles Kanjama, who is also the chair of the Kenya Christian Professionals Forum, said: "In the internal forum, you cannot make somebody believe something that they don't want to believe – you can't compel them. But at the external forum, when your belief leads you to actions that endanger or harm others, at that point the State can get involved."

Bishop Oginde added: "This code of conduct is not a weapon but an agreement on what we can do because the danger we have now is that churches can close by being shut down by government. It has happened before."

The launch of the Code of Conduct and Governance Guidelines for the Church in Kenya comes weeks after the government deregistered 5 churches including cult leader Paul Mackenzie's Good News International Ministries and Pastor Ezekiel Odero's New Life Prayer Center and Church.

Pastor Odero has since launched a legal challenge against the government's decision.

Once signed and adopted, the Code of Conduct for the Church in Kenya will undergo [an] implementation process, with review and amendment in future likely.

Aug 19, 2023

Kenyan Govt Bans Churches Linked To Cult Deaths Of Over 400 Worshippers Compelled To Starve 'To Meet Jesus'

Sahara Reporters

August 18, 2023

The Kenyan government has banned the church of a suspected cult leader accused of compelling more than 400 of his followers to starve themselves to death in order to “meet Jesus.

The registrar of societies in a gazette notice on Friday said that the licence of the self-proclaimed Pastor Paul Nthenge Mackenzie's Good News International Ministries was revoked effective from May 19, 2023, an AFP report published by Barron’s New says.

Mackenzie was accused of inciting his followers to starve to death in order to "meet Jesus”, an action that led to the death of over 400 worshippers of the church.

However, official autopsies reportedly showed that while starvation appeared to be the main cause of the death of the church members, some of the victims, including children, were strangled, beaten or suffocated.

Kenyan authorities also banned four other churches including the New Life Prayer Centre and Church headed by flamboyant televangelist, Ezekiel Odero, who has been linked to Mackenzie.

Odero, who was arrested in April following the discovery of human remains in Shakahola forest near the coastal town of Malindi, the bodies which police were that of Mackenzie's followers, is under investigation on charges including murder, aiding suicide, radicalisation and money laundering.

But while prosecutors have linked the two preachers to the death of the church members, Odero was granted bail in May while a court last week extended Mackenzie's detention for a further 47 days pending further investigation.

Aug 11, 2023

Cults Continue to Cause Death in the 21st Century

Politics Today

WORLD

August 11, 2023

In the heart of Kenya's Shakahola Forest, a shocking discovery has unearthed a haunting story of tragedy and fanaticism.

In the heart of Kenya’s Shakahola Forest, a shocking discovery has unearthed a haunting story of tragedy and fanaticism. Authorities have uncovered the dark secrets of an alleged starvation cult following a tip-off from a concerned father. In the depths of the forest, more than 400 bodies were found, including innocent children. These victims fell prey to a doomsday cult led by the charismatic televangelist Pastor Paul Nthenge Mackenzie, head of the Good News International Church. The cult preached a disastrous doctrine that promised salvation through self-starvation. As the authorities delved deeper into the cult’s activities, the sinister nature of its their beliefs became evident.

This nightmarish saga dates back to the early 2000s when Pastor Mackenzie, a former taxi driver, founded the cult. Initially attracting followers with fiery sermons, Mackenzie’s messages took a dark turn over time, leading to the rapid radicalization of his followers. By 2010, his teachings focused on “doomsday” prophecies, and he began manipulating his followers for financial gain.

Mackenzie preached that his followers had to give up their earthly possessions to truly follow “the cause”. He built a spiritual camp for his loyal followers in the remote area of Shakahola Forest. He instructed them to abandon education, shun medical care, and refuse vaccinations, branding doctors as worshippers of another god. They were ordered to give up conventional food, dismissing it as “worldly food”, and told to destroy their government documents, including identity cards and birth certificates.

Eyewitness accounts reveal that the cult leader urged parents to strangle their starving children. Shockingly, Mackenzie had previously been arrested for various child deaths in 2017, 2019, and 2023, but was released on bail. When the events of the Shakahola cult came to light, President William Ruto remarked that Mackenzie’s amounted to terrorism and that he belonged in prison.

Criminal cults replicate similar patterns

However, this is not an isolated case. Throughout history, the world has witnessed similar cults with disastrous endings, such as Jonestown, the Rajneesh Movement, and the Ten Commandments of God Movement.

Experts, including Joe Navarro, a veteran of the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Program, suggest that cult leaders are often pathologically narcissistic. They have an exaggerated belief in their own importance, claim to have all the answers, and demand unwavering loyalty. These cults erode individual autonomy and critical thinking, leading members to follow the leader’s orders without question, sometimes leading to their own destruction or violent actions.

The dangers posed by such cults go beyond individual tragedies with unquestioning obedience to authority raising national and international security issues. Historical examples, such as Charles Manson’s cult and the Rajneesh Movement’s armed conflict with local authorities, illustrate the potential for violence and conflict arising from these groups.

The Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God (MRTCG) in Uganda is a harrowing example of how such groups can become a serious national and international security threat. In March 2000, the cult’s leaders (Joseph Kibweteere, Joseph Kasapurari, John Kamagara, Dominic Kataribabo, and Credonia Mwerinde) prophesied the end of the world, but when the predicted doomsday did not materialize, chaos broke out within the cult.

On March 17, 2000, more than 530 members, including women and children, were found dead in the cult’s Kanungu commune. The cult leaders had locked their followers in the communal church building and committed mass murder by setting fire to the building.

Cults exploit people’s vulnerabilities

Charismatic and authoritarian cult leaders, such as those involved in the cases above, possess an aura that attracts individuals to their cause. They prey on the vulnerability of their followers, promising salvation, enlightenment, or a vision of the apocalypse that resonates with their deepest fears and desires.

These cults often display hostility towards the outside world, branding it as corrupt or evil. This hostility has translated into conflict and violence, as seen in the Jonestown Massacre and the actions of the Rajneesh Movement.

Moreover, the international reach of cults such as the Rajneesh Movement and Aum Shinrikyo (a Japanese new religious movement and doomsday cult) poses a challenge to law enforcement and intelligence agencies. These cults set up operations in several countries and attract followers from different backgrounds. Their global presence allows them to manipulate vulnerable individuals from various regions, causing damage that transcends national borders.

Social media and cults

The Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo established international centers in various countries, including Russia, the United States, Germany, and others. Similarly, around 1981, the leaders of the Rajneeshee movement (Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and Ma Anand Sheela) were threatened with punitive action by the Indian authorities. In response, they decided to leave India. They set up a new religious settlement in the United States.

Today cult leaders can exploit communication technologies better, particularly social media and online platforms, to reach potential followers worldwide. This enables them to internationalize their movements and recruit and radicalize individuals across continents. In extreme cases where cults go haywire, they may be involved in acts of terrorism or violence that cross national borders. The breakdown of social norms and governance within these cult communities creates a hotbed for criminal activity and human rights abuses, affecting the international community as a whole.

The cautionary tale of the starvation cult in Kenya’s Shakahola Forest and its predecessors highlight the dangerous appeal of charismatic cult leaders and the tragic consequences of their manipulative doctrines. The grim impact of this cult, which claimed hundreds of lives, including innocent children, serves as a reminder of the dangers posed by such fanatical groups.

Ezgi Yaramanoglu

Ezgi Yaramanoğlu graduated from the department of Political Science and International Relations at Yeditepe University. She is currently pursuing her MA in Conflict and Development Studies at Gent University and she is doing her second bachelors in Psychology at Akademia Ekonomiczno-Humanistyczna w Warszawie.

https://politicstoday.org/cults-continue-to-cause-death-in-the-21st-century/