The facts on why facts alone can’t fight false beliefs facts on why facts alone can’t fight false beliefs

JULIE BECK

The Atlantic

March 13, 2017

“I remember looking at her and thinking, ‘She’s totally lying.’ At the same time, I remember something in my mind saying, ‘And that doesn’t matter.’” For Daniel Shaw, believing the words of the guru he had spent years devoted to wasn’t blind faith exactly. It was something he chose. “I remember actually consciously making that choice.”

There are facts, and there are beliefs, and there are things you want so badly to believe that they become as facts to you.

Back in 1980, Shaw had arrived at a

Siddha Yoga meditation center in upstate New York during what he says was a “very vulnerable point in my life.” He’d had trouble with relationships, and at work, and none of the therapies he’d tried really seemed to help. But with Siddha Yoga, “my experiences were so good and meditation felt so beneficial [that] I really walked into it more and more deeply. At one point, I felt that I had found my life’s calling.” So, in 1985, he saved up money and flew to India to join the staff of Gurumayi Chidvilasananda, the spiritual leader of the organization, which had tens of thousands of followers. Shaw rose through the ranks, and spent a lot of time traveling for the organization, sometimes with Gurumayi, sometimes checking up on centers around the U.S.

But in 1994, Siddha Yoga became the subject of an exposé in The New Yorker. The article by Lis Harris detailed allegations of sexual abuse against Gurumayi’s predecessor, as well as accusations that Gurumayi forcibly ousted her own brother, Nityananda, from the organization. Shaw says he was already hearing “whispers” of sexual abuse when he joined in the 80s, but “I chose to decide that they couldn’t be true.” One day shortly after he flew to India, Shaw and the other staff members had gathered for a meeting, and Gurumayi had explained that her brother and popular co-leader was leaving the organization voluntarily. That was when Shaw realized he was being lied to. And when he decided it didn’t matter—“because she’s still the guru, and she’s still only doing everything for the best reasons. So it doesn’t matter that she’s lying.’” (For her part, Gurumayi has denied banishing her brother, and Siddha Yoga is still going strong. Gurumayi, though unnamed, is presumed to be the featured guru in Elizabeth Gilbert’s 2006 bestseller Eat, Pray, Love.)

But that was then. Shaw eventually found his way out of Siddha Yoga and became a psychotherapist. These days, he dedicates part of his practice to working with former cult members and family members of people in cults.

The theory of cognitive dissonance—the extreme discomfort of simultaneously holding two thoughts that are in conflict—was developed by the social psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1950s. In a famous study, Festinger and his colleagues embedded themselves with a doomsday prophet named Dorothy Martin and her cult of followers who believed that spacemen called the Guardians were coming to collect them in flying saucers, to save them from a coming flood. Needless to say, no spacemen (and no flood) ever came, but Martin just kept revising her predictions. Sure, the spacemen didn’t show up today, but they were sure to come tomorrow, and so on. The researchers watched with fascination as the believers kept on believing, despite all the evidence that they were wrong.

“A man with a conviction is a hard man to change,” Festinger, Henry Riecken, and Stanley Schacter wrote in When Prophecy Fails, their 1957 book about this study. “Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point … Suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong: what will happen? The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken, but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before.”

This doubling down in the face of conflicting evidence is a way of reducing the discomfort of dissonance, and is part of a set of behaviors known in the psychology literature as “motivated reasoning.” Motivated reasoning is how people convince themselves or remain convinced of what they want to believe—they seek out agreeable information and learn it more easily; and they avoid, ignore, devalue, forget, or argue against information that contradicts their beliefs.

It starts at the borders of attention—what people even allow to breach their bubbles. In a 1967 study, researchers had undergrads listen to some pre-recorded speeches, with a catch—the speeches were pretty staticky. But, the participants could press a button that reduced the static for a few seconds if they wanted to get a clearer listen. Sometimes the speeches were about smoking—either linking it to cancer, or disputing that link—and sometimes it was a speech attacking Christianity. Students who smoked were very eager to tune in to the speech that suggested cigarettes might not cause cancer, whereas nonsmokers were more likely to slam on the button for the antismoking speech. Similarly, the more-frequent churchgoers were happy to let the anti-Christian speech dissolve into static while the less religious would give the button a few presses.

Outside of a lab, this kind of selective exposure is even easier. You can just switch off the radio, change channels, only like the Facebook pages that give you the kind of news you prefer. You can construct a pillow fort of the information that’s comfortable.

Most people aren’t totally ensconced in a cushiony cave, though. They build windows in the fort, they peek out from time to time, they go for long strolls out in the world. And so, they will occasionally encounter information that suggests something they believe is wrong. A lot of these instances are no big deal, and people change their minds if the evidence shows they should—you thought it was supposed to be nice out today, you step out the door and it’s raining, you grab an umbrella. Simple as that. But if the thing you might be wrong about is a belief that’s deeply tied to your identity or worldview—the guru you’ve dedicated your life to is accused of some terrible things, the cigarettes you’re addicted to can kill you—well, then people become logical Simone Bileses, doing all the mental gymnastics it takes to remain convinced that they’re right.

People see evidence that disagrees with them as weaker, because ultimately, they’re asking themselves fundamentally different questions when evaluating that evidence, depending on whether they want to believe what it suggests or not, according to psychologist Tom Gilovich. “For desired conclusions,” he writes, “it is as if we ask ourselves ‘Can I believe this?’, but for unpalatable conclusions we ask, ‘Must I believe this?’” People come to some information seeking permission to believe, and to other information looking for escape routes.

In 1877, the philosopher William Kingdon Clifford wrote an essay titled “The Ethics of Belief,” in which he argued: “It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone to believe anything on insufficient evidence.”

Lee McIntyre takes a similarly moralistic tone in his 2015 book Respecting Truth: Willful Ignorance in the Internet Age: “The real enemy of truth is not ignorance, doubt, or even disbelief,” he writes. “It is false knowledge.”

Whether it’s unethical or not is kind of beside the point, because people are going to be wrong and they’re going to believe things on insufficient evidence. And their understandings of the things they believe are often going to be incomplete—even if they’re correct. How many people who (rightly) believe climate change is real could actually explain how it works? And as the philosopher and psychologist William James noted in an address rebutting Clifford’s essay, religious faith is one domain that, by definition, requires a person to believe without proof.

Still, all manner of falsehoods—conspiracy theories, hoaxes, propaganda, and plain old mistakes—do pose a threat to truth when they spread like fungus through communities and take root in people’s minds. But the inherent contradiction of false knowledge is that only those on the outside can tell that it’s false. It’s hard for facts to fight it because to the person who holds it, it feels like truth.

At first glance, it’s hard to see why evolution would have let humans stay resistant to facts. “You don’t want to be a denialist and say, ‘Oh, that’s not a tiger, why should I believe that’s a tiger?’ because you could get eaten,” says McIntyre, a research fellow at the Center for Philosophy and History of Science at Boston University.

But from an evolutionary perspective, there are more important things than truth. Take the same scenario McIntyre mentioned and flip it on its head—you hear a growl in the bushes that sounds remarkably tiger-like. The safest thing to do is probably high-tail it out of there, even if it turns out it was just your buddy messing with you. Survival is more important than truth.

“Having social support, from an evolutionary standpoint, is far more important than knowing the truth.”

And of course, truth gets more complicated when it’s a matter of more than just “Am I about to be eaten or not?” As Pascal Boyer, an anthropologist and psychologist at Washington University in St. Louis points out in his forthcoming book The Most Natural Thing: How Evolution Explains Human Societies: “The natural environment of human beings, like the sea for dolphins or the ice for polar bears, is information provided by others, without which they could not forage, hunt, choose mates, or build tools. Without communication, no survival for humans.”

In this environment, people with good information are valued. But expertise comes at a cost—it requires time and work. If you can get people to believe you’re a good source without actually being one, you get the benefits without having to put in the work. Liars prosper, in other words, if people believe them. So some researchers have suggested motivated reasoning may have developed as a “shield against manipulation.” A tendency to stick with what they already believe could help protect people from being taken in by every huckster with a convincing tale who comes along.

“This kind of arms-race between deception and detection is common in nature,” Boyer writes.

Spreading a tall tale also gives people something even more important than false expertise—it lets them know who’s on their side. If you accuse someone of being a witch, or explain why you think the contrails left by airplanes are actually spraying harmful chemicals, the people who take you at your word are clearly people you can trust, and who trust you. The people who dismiss your claims, or even those who just ask how you know, are not people you can count on to automatically side with you no matter what.

“You spread stories because you know that they’re likely to be a kind of litmus test, and the way people react will show whether they’re prepared to side with you or not,” Boyer says. “Having social support, from an evolutionary standpoint, is far more important than knowing the truth about some facts that do not directly impinge on your life.” The meditation and sense of belonging that Daniel Shaw got from Siddha Yoga, for example, was at one time more important to his life than the alleged misdeeds of the gurus who led the group.

Though false beliefs are held by individuals, they are in many ways a social phenomenon. Dorothy Martin’s followers held onto their belief that the spacemen were coming, and Shaw held onto his reverence for his guru, because those beliefs were tethered to a group they belonged to, a group that was deeply important to their lives and their sense of self.

Shaw describes the motivated reasoning that happens in these groups: “You’re in a position of defending your choices no matter what information is presented,” he says, “because if you don’t, it means that you lose your membership in this group that’s become so important to you.” Though cults are an intense example, Shaw says people act the same way with regard to their families or other groups that are important to them.

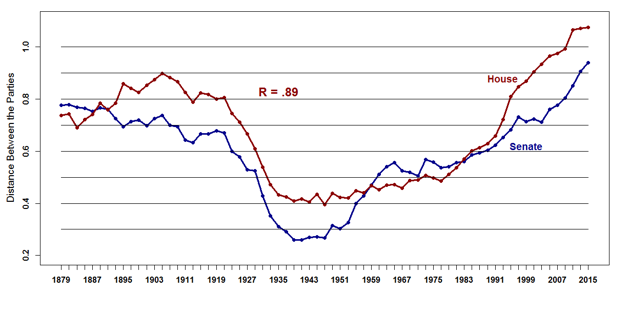

And in modern America, one of the groups that people have most intensely hitched their identities to is their political party. Americans are more politically polarized than they’ve been in decades, possibly ever. There isn’t public-opinion data going back to the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans, of course. But political scientists Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal look at the polarization in Congress. And the most recent data shows that 2015 had the highest rates of polarization since 1879, the earliest year for which there’s data. And that was even before well, you know.

Party Polarization, 1879-2015

Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal, voteview.com

Now, “party is a stronger part of our identity,” says Brendan Nyhan, a professor of government at Dartmouth College. “So it’s easy to see how we can slide into a sort of cognitive tribalism.”

Though as the graph above shows, partisanship has been on the rise in the United States for decades, Donald Trump’s election, and even his brief time as president, have made partisanship and its relationship to facts seem like one of the most urgent questions of the era. In the past couple of years, fake news stories perfectly crafted to appeal to one party or the other have proliferated on social media, convincing people that the Pope had endorsed Trump or that Rage Against the Machine was reuniting for an anti-Trump album. While some studies suggest that conservatives are more susceptible to fake news—one fake news creator told NPR that stories he’d written targeting liberals never gained as much traction—after the election, the tables seem to have turned. As my colleague Robinson Meyer reported, in recent months there’s been an uptick in progressive fake news, stories that claim Trump is about to be arrested or that his administration is preparing for a coup.

Though both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump were disliked by members of their own parties—with a “Never Trump” movement blooming within the Republican Party—ultimately most people voted along party lines. Eighty-nine percent of Democrats voted for Clinton and 88 percent of Republicans voted for Trump, according to CNN’s exit polls.

Carol Tavris, a social psychologist and co-author of Mistakes Were Made, But Not by Me, says that for Never Trump Republicans, it must have been “uncomfortable to them to feel they could not be wholeheartedly behind their candidate. You could hear the dissonance humming within them. We had a year of watching with interest as Republicans struggled to resolve this. Some resolved it by: ‘Never Trump but never Hillary, either.’ Others resolved it by saying, ‘I’m going to hold my nose and vote for him because he’s going to do the things that Republicans do in office.’”

“Partisanship has been revealed as the strongest force in U.S. public life—stronger than any norms, independent of any facts,” Vox’s David Roberts wrote in his extensive breakdown of the factors that influenced the election. The many things that, during the campaign, might have seemed to render Trump unelectable—boasting about sexual assault, encouraging violence at his rallies, attacking an American-born judge for his Mexican heritage—did not ultimately cost him the support of the majority of his party. Republican commentators and politicians even decried Trump as not a true conservative. But he was the Republican nominee, and he rallied the Republican base.

In one particularly potent example of party trumping fact, when shown photos of Trump’s inauguration and Barack Obama’s side by side, in which Obama clearly had a bigger crowd, some Trump supporters identified the bigger crowd as Trump’s. When researchers explicitly told subjects which photo was Trump’s and which was Obama’s, a smaller portion of Trump supporters falsely said Trump’s photo had more people in it.

While this may appear to be a remarkable feat of self-deception, Dan Kahan thinks it’s likely something else. It’s not that they really believed there were more people at Trump’s inauguration, but saying so was a way of showing support for Trump. “People knew what was being done here,” says Kahan, a professor of law and psychology at Yale University. “They knew that someone was just trying to show up Trump or trying to denigrate their identity.” The question behind the question was, “Whose team are you on?”

In these charged situations, people often don’t engage with information as information but as a marker of identity. Information becomes tribal.

In a New York Times article called “The Real Story About Fake News Is Partisanship,” Amanda Taub writes that sharing fake news stories on social media that denigrate the candidate you oppose “is a way to show public support for one’s partisan team—roughly the equivalent of painting your face with team colors on game day.”

This sort of information tribalism isn’t a consequence of people lacking intelligence or of an inability to comprehend evidence. Kahan has previously written that whether people “believe” in evolution or not has nothing to do with whether they understand the theory of it—saying you don’t believe in evolution is just another way of saying you’re religious. Similarly, a recent Pew study found that a high level of science knowledge didn’t make Republicans any more likely to say they believed in climate change, though it did for Democrats.

What’s more, being intelligent and informed can often make the problem worse. The higher someone’s IQ, the better they are at coming up with arguments to support a position—but only a position they already agree with, as one study showed. High levels of knowledge make someone more likely to engage in motivated reasoning—perhaps because they have more to draw on when crafting a counterargument.

People also learn selectively—they’re better at learning facts that confirm their worldview than facts that challenge it. And media coverage makes that worse. While more news coverage of a topic seems to generally increase people’s knowledge of it, one paper, “Partisan Perceptual Bias and the Information Environment,” showed that when the coverage has implications for a person’s political party, then selective learning kicks into high gear.

“You can have very high levels of news coverage of a particular fact or an event and you see little or no learning among people who are motivated to disagree with that piece of information,” says Jennifer Jerit, a professor of political science at Stony Brook University and a co-author of the partisan-perception study. “Our results suggest that extraordinary levels of media coverage may be required for partisans to incorporate information that runs contrary to their political views,” the study reads. For example, Democrats are overwhelmingly supportive of bills to ban the chemical BPA from household products, even though the FDA and many scientific studies have found it is safe at the low levels currently used. This reflects a “chemophobia” often seen among liberals, according to Politico.

Fact-checking erroneous statements made by politicians or cranks may also be ineffective. Nyhan’s work has shown that correcting people’s misperceptions often doesn’t work, and worse, sometimes it creates a backfire effect, making people endorse their misperceptions even more strongly.

Sometimes during experimental studies in the lab, Jerit says, researchers have been able to fight against motivated reasoning by priming people to focus on accuracy in whatever task is at hand, but it’s unclear how to translate that to the real world, where people wear information like team jerseys. Especially because a lot of false political beliefs have to do with issues that don’t really affect people’s day-to-day lives.

“Most people have no reason to have a position on climate change aside from expression of their identity,” Kahan says. “Their personal behavior isn’t going to affect the risk that they face. They don't matter enough as a voter to determine the outcome on policies or anything like this. These are just badges of membership in these groups, and that’s how most people process the information.”

In 2016, Oxford Dictionaries chose “post-truth” as its word of the year, defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

It was a year when the winning presidential candidate lied almost constantly on the campaign trail, when fake news abounded, and when people cocooned themselves thoroughly in social-media spheres that only told them what they wanted to hear. After careening through a partisan hall of mirrors, the “facts” that came through were so twisted and warped that Democrats and Republicans alike were accused of living in a “filter bubble,” or an “echo chamber,” or even an “alternate reality.”

Farhad Manjoo’s book, True Enough: Learning to Live in a Post-Fact Society, sounds like it could have come out yesterday—with its argument about how the media is fragmenting, how belief beats out fact, and how objective reality itself gets questioned—but it was actually published in 2008.

“Around the time [the book] came out, I was a little bit unsure how speculative and how real the idea was,” says Manjoo, who is now a technology columnist for The New York Times. “One of my arguments was, in politics, you don’t pay a penalty for lying.” At the time, a lot of lies were going around about presidential candidate Barack Obama—that he was a Muslim, that he wasn’t born in the United States—lies that did not ultimately sink him.

“Here was a person who was super rational, and believed in science, and was the target of these factless claims, but won anyway,” Manjoo says. “It really seemed like that election was a vindication of fact and truth, which in retrospect, I think it was just not.”

There was plenty of post-truth to go around during the Obama administration, whether it was the birther rumors (famously perpetuated by the current president) that just wouldn’t die, or the debate over the nonexistent “death panels” in the Affordable Care Act.

“I started to get a sense that my idea was probably realer than I thought,” Manjoo says. “And then you had the 2016 election, which confirmed every worst fear of mine.”

But the problem, Nyhan says, with “post-truth, post-fact language is it suggests a kind of golden age that never existed in which political debate was based on facts and truth.”

People have always been tribal and have always believed things that aren’t true. Is the present moment really so different, or do the stakes just feel higher?

Partisanship has surely ramped up—but Americans have been partisan before, to the point of civil war. Today’s media environment is certainly unique, though it’s following some classic patterns. This is hardly the first time there have been partisan publications, or many competing outlets, or even information silos. People often despair at the loss of the mid-20th-century model, when just a few newspapers and TV channels fed people most of their unbiased news vegetables. But in the 19th century, papers were known for competing for eyeballs with sensational headlines, and in the time of the Founding Fathers, Federalist and Republican papers were constantly sniping at each other. In times when communication wasn’t as easy as it is now, news was more local—you could say people were in geographical information silos. The mid-20th-century “mainstream media” was an anomaly.

The situation now is in some ways a return to the bad old days of bias and silos and competition, “but it’s like a supercharged return,” Manjoo says. “It’s not just that I’m reading news that confirms my beliefs, but I’m sharing it and friending other people, and that affects their media. I think it’s less important what a news story says than what your friend says about the news story.” These silos are also no longer geographical, but ideological and thus less diverse. A recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that analyzed 376 million Facebook users’ interactions with 900 news outlets reports that “selective exposure drives news consumption.”

Not everyone, however, agrees that the silos exist. Kahan says he’s not convinced: “I think that people have a preference for the sources that support their position. That doesn’t mean that they're never encountering what the other side is saying.” They’re just dismissing it when they do.

The sheer scale of the internet allows you to find evidence (if sometimes dubious evidence) for any claim you want to believe, and counterevidence against any claim you don’t want to have to believe. And because humans didn’t evolve to operate in such a large sea of people and information, Boyer says people can be fooled into thinking some ideas are more widespread than they really are.

“When I was doing fieldwork in small villages in Africa, I've seen examples of people who have a strange belief,” he says. “[For example], they think that if they recite an incantation they can make a small object disappear. Now, most people around them just laugh and tell them that’s stupid. And that’s it. And the belief kind of disappears.”

But as a community gets larger, the likelier it is that a person can find someone else who shares their strange belief. And if the “community” is everyone in the world with an internet connection who speaks your language, well.

“If you encounter 10 people who seem to have roughly the same idea, then it fools your system into thinking that it must be a probable idea because lots of people agree with it,” Boyer says. “One thing you assume, unconsciously, is that these 10 people came to the same belief independently. You don’t think that nine of these are just repeating something that the 10th one said.”

Part of the problem is that society has advanced to the point that believing what’s true often means accepting things you don’t have any firsthand experience of and that you may not completely understand. Sometimes it means disbelieving your own senses—Earth doesn’t feel like it’s moving, after all, and you can’t see climate change out your window.

In areas where you lack expertise, you have to rely on trust. Even Clifford acknowledges this—it’s acceptable, he says, to believe what someone else tells you “when there is reasonable ground for supposing that he knows the matter of which he speaks.”

The problem is that who and what people trust to give them reliable information is also tribal. Deferring to experts might seem like a good start, but Kahan has found that people see experts who agree with them as more legitimate than experts who don’t.

In the United States, people are less generally trusting of each other than they used to be. Since 1972, the General Social Survey has asked respondents: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” As of 2014, the most recent data, the number of people saying most others can be trusted was at a historic low.

Percent of Americans Who Say Most People Can Be Trusted

On the other hand, there’s “particularized trust”—specifically, the trust you have for people in your groups. “Particularized trust destroys generalized trust,” Manjoo wrote in his book. “The more that people trust those who are like themselves—the more they trust people in their own town, say—the more they distrust strangers.”

This fuels tribalism. “Particularized trusters are likely to join groups composed of people like themselves—and to shy away from activities that involve people they don’t see as part of their moral community,” writes Eric Uslaner, a professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland, College Park.

So people high on the particularized-trust scale would be more likely to believe information that comes from others in their groups, and if those groups are ideological, the people sharing that information probably already agree with them. And so it spirals.

This is also a big part of why people don’t trust the media. Not that news articles are never biased, but a hypothetical perfectly evenhanded piece of journalism, that fairly and neutrally represented all sides would still likely be seen as biased by people on each side. Because, Manjoo writes, everyone thinks their side has the best evidence, and therefore if the article were truly objective, it would have emphasized their side more.

This is the attitude Trump has taken toward the media, calling any unfavorable coverage of him—even if it’s true—“unfair” and “fake news.” On the other hand, outlets that are biased in his favor, like Fox and Friends and the pro-Trump conservative blog The Gateway Pundit, Trump bills as “very honorable” and he invites them to the White House. (This is a reversal of fortune for Fox, which got a similar “fake news” style brush-off in 2009, when Obama’s communications director said the administration wouldn’t “legitimize them as a news organization.”) Trump’s is an extreme, id-fueled version of particularized trust, to be sure, but it’s akin to a mind-set many are prone to. Objectivity is a valiant battle, but sometimes, a losing one.

“Alternative facts” is a phrase that will live in infamy. Trump counselor Kellyanne Conway famously used it to describe White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer’s lie that Trump’s inauguration had drawn the “largest audience to ever witness an inauguration—period.”

Spicer has also said to reporters, “I think sometimes we can disagree with the facts.”

These are some of the more explicit statements from an administration that shows in ways subtle and not-at-all subtle that it often does not, as McIntyre would put it, “respect the truth.” This sort of flippant disregard for objective reality is deeply troubling, but the extreme nature of it also exposes more clearly something that’s always been true about politics: that sometimes when we argue about the facts, we’re not arguing about the facts at all.

The experiment where Trump supporters were asked about the inauguration photos is one example. In a paper on political misperceptions, Nyhan suggests another: a survey asking people whether they agree with the statement “The murder rate in the United States is the highest it’s been in 45 years,” something Trump often said on the campaign trail, as well as something that’s not true. “Because the claim is false,” Nyhan writes, “the most accurate response is to disagree. But what does it mean if a person agrees with the statement?”

It becomes unclear whether the person really believes that the false statement is true, or whether they’re using it as a shortcut to express something else—their support for Trump regardless of the validity of his claims, or just the fact that they feel unsafe and they’re worried about crime. Though for the media outlets that are fact-checking these things, it’s a matter of truth and falsehood, for the ordinary person evaluating, adopting, rejecting, or spreading false beliefs, that may not be what it’s really about.

Sometimes when we argue about the facts, we’re not arguing about the facts at all.

These are more often disputes over values, Kahan says, about what kind of society people want and which group or politician aligns with that. “Even if a fact is corrected, why is that going to make a difference?” he asks. “That’s not why they were supporting the person in the first place.”

So what would get someone to change their mind about a false belief that is deeply tied to their identity?

“Probably nothing,” Tavris says. “I mean that seriously.”

But of course there are areas where facts can make a difference. There are people who are just mistaken or who are motivated to believe something false without treasuring the false belief like a crown jewel.

“Personally my own theory is that there’s a slide that happens,” McIntyre says. “This is why we need to teach critical thinking, and this is why we need to push back against false beliefs, because there are some people who are still redeemable, who haven’t made that full slide into denialism yet. I think once they’ve hit denial, they’re too far gone and there’s not a lot you can do to save them.”

There are small things that could help. One recent study suggests that people can be “inoculated” against misinformation. For example, in the study, a message about the overwhelming scientific consensus on climate change included a warning that “some politically motivated groups use misleading tactics to try to convince the public that there is a lot of disagreement among scientists.” Exposing people to the fact that this misinformation is out there should make them more resistant to it if they encounter it later. And in the study at least, it worked.

While there’s no erasing humans’ tribal tendencies, muddying the waters of partisanship could make people more open to changing their minds. “We know people are less biased if they see that policies are supported by a mix of people from each party,” Jerit says. “It doesn’t seem like that’s very likely to happen in this contemporary period, but even to the extent that they see within party disagreement, I think that is meaningful. Anything that's breaking this pattern where you see these two parties acting as homogeneous blocks, there’s evidence that motivated reasoning decreases in these contexts.”

It’s also possible to at least imagine a media environment that’s less hospitable to fake news and selective exposure than our current one, which relies so heavily on people’s social-media networks.

I asked Manjoo what a less fake-newsy media environment might look like.

“I think we need to get to an information environment where sharing is slowed down,” Manjoo says. “A really good example of this is Snapchat. Everything disappears after a day—you can’t have some lingering thing that gets bigger and bigger.”

Facebook is apparently interested in copying some of Snapchat’s features—including the disappearing messages. “I think that would reduce virality, and then you could imagine that would perhaps cut down on sharing false information,” Manjoo says. But, he caveats: “Things must be particularly bad if you’re looking at Snapchat for reasons of hope.”

So much of how people view the world has nothing to do with facts. That doesn’t mean truth is doomed, or even that people can’t change their minds. But what all this does seem to suggest is that, no matter how strong the evidence is, there’s little chance of it changing someone’s mind if they really don’t want to believe what it says. They have to change their own.

As previously noted, Daniel Shaw ultimately left Siddha Yoga. But it took a long time. “Before that [New Yorker] article came out,” he says, “I started to learn about what was going to be in that article, and the minute I heard it is the minute I left that group, because immediately it all clicked together. But it had taken at least five years of this growing unease and doubt, which I didn’t want to know about or face.”

It seems like if people are going to be open-minded, it’s more likely to happen in group interactions. As Manjoo noted in his book, when the U.S. government was trying to get people to eat organ meat during World War II (you know, to save the good stuff for our boys), researchers found that when housewives had a group discussion about it, rather than just listening to a nutritionist blather on about what a good idea it was, they were five times more likely to actually cook up some organs. And groups are usually better at coming up with the correct answers to reasoning tasks than individuals are.

Of course, the wisdom of groups is probably diminished if everyone in a group already agrees with each other.

“One real advantage of group reasoning is that you get critical feedback,” McIntyre says. “If you’re in a silo, you don’t get critical feedback, you just get applause.”

But if the changes are going to happen at all, it’ll have to be “on a person-to-person level,” Shaw says.

He tells me about a patient of his, whose family is involved in “an extremely fundamentalist Christian group. [The patient] has come to see a lot of problems with the ideology and maintains a relationship with his family in which he tries to discuss in a loving and compassionate way some of these issues,” Shaw says. “He is patient and persistent, and he chips away, and he may succeed eventually.”

“But are they going to listen to a [news] feature about why they’re wrong? I don’t think so.”

When someone does change their mind, it will probably be more like the slow creep of Shaw’s disillusionment with his guru. He left “the way most people do: Sort of like death by a thousand cuts.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/03/this-article-wont-change-your-mind/519093/