Sect spotlighted by Marshall fire abuses children, exploits followers and teaches racism, former members say

SHELLY BRADBURY

The Denver Post

March 3, 2022

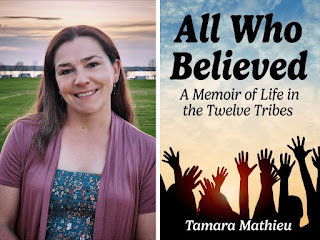

John I. Post, pictured in Portland, Maine, on Feb. 12, 2022, was born and raised in the Twelve Tribes. He was subjected to abuse as a child in the cult, mistreatment he said was made worse because he is deaf. Post, who is also gay, which is forbidden by the cult, escaped in 1999 when he was 19.

On a fall day in 1999, 19-year-old John I. Post packed up his birth certificate, Social Security card, state identification, favorite blanket and pictures of his family and prepared to leave the religious cult into which he’d been born and raised.

He’d been taught his whole life that anyone who left the Twelve Tribes would die. He had no money. Agonized over the decision to leave. But he couldn’t stay. He planned to walk into town and call a friend for help.

When he finally stood up to leave the Vermont compound, some 15 cult members blocked his path outside, forming a wall. They prayed and warned there would be consequences if he walked out of God’s protection. He’d probably die. Post shook as he moved by them.

“My heart was just pounding and pounding. Was something going to happen to me? I didn’t know,” Post, who is deaf, said in an interview through an interpreter.

As he walked the mile into town, his father followed, imploring him to stay.

“I finally said to my father, ‘Look, please, accept this is my decision,’” Post, 43, said. “And finally he didn’t say anything and he walked away.”

Post was free.

“I’ll never go back,” he said. “Never, not at all. I just feel like, the Twelve Tribes, they are evil.”

The Twelve Tribes religious sect burst into the news in Colorado in January, when authorities confirmed they were investigating the possibility that the deadly Marshall fire, the most destructive wildfire in state history, might have started on the group’s compound off Eldorado Springs Drive in Boulder County. Investigators have not yet pinpointed the cause of the fire that destroyed more than 1,000 homes and are investigating other potential ignition points as well.

Few on the Front Range know much about the insular religious group, whose 3,000-some members live communally in Colorado and across the nation and world, and take pains to present an innocuous front to outsiders.

The Twelve Tribes attracts new members with a folksy peace-and-love, all-are-welcome message, but underneath that hollow promise of utopia lies a manipulative cult that seeks to maintain complete control of its followers, 10 former members told The Denver Post in 26 hours of interviews. The Post reviewed nearly 400 pages of Twelve Tribes’ teachings and combed through court, real estate, business and historical records in reporting on the sect.

In a series of three stories over the next week, The Post will detail accounts of ex-members living inside the Twelve Tribes, spotlighting three major problems identified by former followers: that the group requires excessive corporal punishment and fails to protect children from sexual abuse, exploits members for labor and money, and espouses racist, misogynistic and homophobic teachings.

“Nobody understands the real horror underneath until you’ve lived it,” said Alina Anderson, a former member born into the cult who left in 2001 at age 14. Anderson, 35, now lives in Boulder and is going by her middle and former married names in this story to avoid being identified by current cult members.

Leaders in the Twelve Tribes contacted by The Post either declined to comment or spoke only briefly, saying they were wary of publicity after past bad experiences with the press. The group also didn’t respond to emailed questions. But those who spoke defended the Twelve Tribes and its practices.

“We try to do good to everyone,” said Tim Pendergrass, a current Twelve Tribes leader who lives in a Florida commune. “It’s amazing how everyone can think bad about you. It just comes with the turf.”

Twelve Tribes members Bob Brooks, Gary Long and the group’s founder Eugene Spriggs seated together around 1982.

Physical restraint and discipline

Founded in Tennessee in 1972 by Elbert Eugene Spriggs, the 50-year-old Twelve Tribes blends Spriggs’ personal beliefs with elements of both Christianity and Judaism.

New members must give up their possessions and names, live in one of the Twelve Tribes’ three dozen worldwide communes and follow the cult’s strict rules, which, former members say, dictate everything from how much toilet paper a member should use (two sheets) to the shape of a member’s eyeglasses (round). Followers are encouraged to cut off all contact with the outside world.

Twelve Tribes: A Black father’s struggle to pull his daughter from the racist cult

The Twelve Tribes moved into Colorado in the early 2000s, first establishing a compound in Manitou Springs before expanding to Boulder in 2010; members now run the Yellow Deli in Boulder and a cafe in Manitou Springs. An estimated 40 people live at the Eldorado Springs Drive compound, and another 25 or so in a house in Manitou Springs.

The largest number of Twelve Tribes communities are in the U.S., but the sect also has a presence in South America, Europe, Canada, Australia and Japan.

The group can be considered a cult because it has a charismatic authoritarian leader, extremist ideology, an all-or-nothing belief system, and uses coercion to control and exploit members, cult expert Janja Lalich said. The Southern Poverty Law Center classifies the Twelve Tribes as a “Christian fundamentalist cult.”

In recent years, the Twelve Tribes has experienced a mass exodus among the first generation of children born and raised in the group. Many — most, by some counts — of the first kids raised in the cult have left, driven out by the group’s practices and leadership’s increasingly tight grip on the shrinking membership that remains.

For many ex-members, the decision to leave came with parenthood.

“I was under no circumstances going to beat my kids the way I was beaten,” said a former member who left in his 30s and spoke to The Post on the condition of anonymity to protect family members still in the cult. “I just could not do it. And you have to if you are there. If you are not beating your kids, you are going to be in big trouble.”

The Twelve Tribes taught that it was different from false religions — like mainstream Christianity — because “their children would follow them,” he said.

But the Twelve Tribes’ children fled in droves. And now, as adults still working through the trauma of their childhoods, they worry for the kids still caught inside.

When a toddler throws a tantrum in the Twelve Tribes, an adult might grab the girl, hold her tight on his lap — perhaps by throwing his leg over hers — restrain both her arms and put his hand over her mouth until she stops fighting back.

The toddler might scream and cry and struggle for an hour. She will not be freed until she surrenders, former members said. The idea is to break her will.

“Kids were supposed to be quiet. And when they weren’t, physical restraint over their bodies and mouths was expected,” said ex-member Jason Wolfe, 46. His brother, a leader in the Twelve Tribes, previously lived in Manitou Springs, and their father helped establish the Boulder community. Wolfe left the group in 2009 and now lives in Virginia; he was 6 when his parents joined.

Jason Wolfe sits in his home in Purcellville, Virginia, on Feb. 10, 2022.

Restraint is part of the Twelve Tribes’ overall approach to child-rearing, which focuses heavily on physical discipline. The Twelve Tribes teaches that children must be spanked with thin, flexible wooden rods — a practice the group has been consistently criticized for but has steadfastly defended, saying it is rooted in Biblical principles.

“Those are longstanding (concerns) that probably won’t be resolved until everyone comes to the understanding everyone will come to,” Pendergrass said.

A January 2000 version of the group’s 348-page Child Training Manual obtained by The Post says children as young as 6 months should be spanked, if they, say, wiggle away from diaper changes.

“The pain received from the balloon stick is more humbling than harmful,” the manual reads. “There is no defense against it… The only way to stop the sting of the rod is to submit. That is exactly what the child will do — submit to his parents’ will and end his rebellion.”

Ex-members who grew up in the Twelve Tribes described being spanked on their bare bottoms, on their hands and on the bottoms of their feet for the slightest perceived offenses; it was not uncommon for parents to spank their child 20 or 30 times each day.

“We were basically beaten down into absolutely nothing so that they could build you up into what they wanted you to be. Asking for seconds at breakfast could get you a spanking,” Anderson said. Adults in the cult were taught to discipline on the first command.

“If you have a 3-year-old son and you say, ‘Stop jumping up and down’ — the chances of that happening on the first time is zero. So that would be a spanking,” said a former 20-year member who previously lived with the cult in Boulder and left in 2016. He spoke on condition of anonymity because his family still lives in the group.

Like most everything in the Twelve Tribes, discipline is communal and guided by social pressure. Offenses that warrant spanking might vary from community to community, or even from family to family, but there is tremendous social pressure to discipline harshly, ex-members said.

Cult members meet once every morning and once every evening for mandatory “gatherings” — worship sessions at which leaders preach. They can be tedious and long, and children are expected to listen without fidgeting.

“If you don’t take your child out and spank them during the teachings, then you’re thought of as not being a good parent,” said Luke Wiseman, 46, a former member who left in 2013 and now lives in Virginia. “People tapped me on the back when I had a 2-year-old son and said, ‘Your son is not listening.’ Then if I don’t take him out and spank him, I’m not ‘receiving.’”

Adults considered to be out-of-bounds are ostracized, shamed and “cut off” from the community until they repent and leaders approve their return. Members who do wrong might also be the subject of a community-wide “public humiliation,” in which the community’s leaders shame the person during a gathering. Some wrongs might be codified into a new teaching that is sent to all Twelve Tribes communities, ex-members said.

“Most people in the Twelve Tribes really live in fear,” said Post, who now lives in Maine. He became deaf as an infant after a bout with meningitis, but his parents didn’t know he’d lost his hearing until he was 4. He was harshly disciplined as a toddler because his parents thought he wasn’t obeying them, when, in reality, he just couldn’t hear their commands, he said. Both parents are still in the Twelve Tribes today.

“Just last year, after 30 years, my parents approached me and apologized for what had happened to me growing up,” Post said. “It was over the top, it was severe and brutal.”

John Post, pictured on Feb. 12, 2022, was born and raised in the Twelve Tribes. He was subjected to abuse as a child in the cult, mistreatment he said was made worse because he is deaf.

Longstanding abuse allegations

The first generation of children in the Twelve Tribes largely grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, and former members described enduring extreme physical abuse during that time. The ex-member who left in his 30s remembered a practice called scourging, in which a child was stripped naked and beaten with a rod from head to toe.

Post and others said adults routinely withheld food from children as a form of discipline, sometimes for days at a time. When Anderson was 6 or 7, she was locked in a dark basement as punishment for taking from the refrigerator.

“The one time that I was locked in the dungeon — it wasn’t a real dungeon but it felt like it — I think that was for more than a day, because we fasted every Friday, so I was used to starving, and it was longer than that,” she said.

On a June day in 1984, authorities in Island Pond, Vermont, raided the Twelve Tribes’ commune there over allegations of child abuse. Police and social workers took more than 100 children into protective custody with plans to examine the kids for signs of abuse. But the plan fell apart when a judge determined the raid was unconstitutional because the search warrant was too general and not supported by concrete evidence of abuse. The children were returned to the commune within hours.

“The raid that happened in 1984, what should have happened is all the children should have been taken and placed in foster care and that should have been the end of the group,” Wolfe said. “There was so much child abuse going on at that time.”

For years afterward, the Twelve Tribes celebrated June 22 as a day of deliverance, a sort of Passover-like event in which God protected the group from the overreach of government. When the children in the raid grew up, some spoke publicly at June 22 remembrances to defend their parents and proclaim they had never been abused.

The day before the 20th anniversary of the raid, Wolfe was included in a meeting with other first-generation kids ahead of the celebration to prepare for the next day’s speeches. Jeanie Swantko, a former public defender who joined the group and married Wiseman’s father after representing him in a child abuse case, told the gathered young adults that they needed to clearly say there had been no abuse. (Swantko couldn’t be reached for comment.)

“I stood up and I was like, ‘You’re dead wrong,'” Wolfe said. “‘There was a (crap)load of abuse, it was everywhere and that was all there was. Why can’t we just say there was child abuse and we’re not OK with it?'”

He was escorted out of the meeting, he said. His brother who is still in the Twelve Tribes, Peter Wolfe, said in a short phone conversation in February that he had a “wonderful upbringing.”

“I did grow up here (in the Twelve Tribes),” he said. “…My wife grew up here. We don’t share any of those views as far as different things that other people might say.”

Both Peter Wolfe and Pendergrass said the Twelve Tribes welcomed visitors and questions, but a local leader denied a request by The Post to visit the group’s Boulder compound. The organization also did not respond to emailed questions about its treatment of children.

Police calls in Colorado

For many years in the Twelve Tribes, physical discipline could be meted out by any adult on any child for any reason, former members said. Anderson was disciplined for wearing her ponytail too high and for looking around — not at her feet — when she walked.

“There was no safe space,” Jason Wolfe said.

In recent years, the Twelve Tribes seems to have shifted toward parents disciplining their own children with less emphasis on all adults disciplining all children, one of several modernizing changes the group has made in response to outside criticism. But ex-members say the Twelve Tribes would never fully abandon the practice of physical discipline, which is still a core tenet.

Logs of police calls to the Twelve Tribes’ compounds in Boulder County and Manitou Springs show that child abuse remains a concern. A 911 caller in May 2020 sent Manitou Springs police to the commune there after a young relative who had visited the group reported that children were being kept in a basement without electricity, according to records provided by Manitou Springs police.

That caller, who asked not to be identified to preserve relationships with her relatives, said police told her they knocked on the door of the commune, asked a few questions and left without going inside. The Twelve Tribes was known to be peaceful and everything seemed OK that night, they told her. Manitou Springs police records show officers spent 13 minutes at the compound; a police spokesman did not know whether officers went inside the home.

In September 2019, child welfare officials and sheriff’s deputies visited the compound in Boulder County and interviewed several people as part of a child protective services investigation, according to a report provided by the sheriff’s office. Deputies went along out of concern the group might be hostile, but the cult members welcomed the inquiry, the report says.

“The children living on the property seemed to be happy and healthy, and they even sang us a couple songs while we were there,” Deputy J. Ryan wrote in the report.

Police also responded to reports of teenagers who ran away from the Colorado properties.

In September 2020, a 16-year-old girl fled the Manitou Springs compound in the middle of the night, according to a police report. In June 2018, a 15-year-old boy who was living in the Boulder commune ran away, sheriff’s records show. The teenager returned after about two days and told deputies he’d ridden his bicycle from the Eldorado Springs Drive commune to Westminster, slept the night on a patch of grass, then continued to ride his bicycle all the way into the 16th Street Mall in Denver, where he spent the day before cycling back to the commune.

“(The boy) appeared very genuine in his statements saying he was not going to do this ever again and that he was sorry for putting his mother and father in such constant worry,” the deputy’s report reads.

The police reports also detail the Jan. 5 arrest of Ron Williams, 50, on a year-old outstanding warrant for felony sexual exploitation of children after Boulder County authorities discovered more than 1,000 images of child sexual abuse in Williams’ possession in 2020. At the time, he was living in a home in Superior; that home burned in the Marshall fire. When he was arrested in January, he’d been staying with the Twelve Tribes, though it’s not clear for how long.

As he was arrested a short walk away from the Twelve Tribes’ compound in Manitou Springs, Officer Ron Johnson described Williams to other officers as “a possible suspect in the Boulder fire” multiple times, according to body camera footage. But Carrie Haverfield, a spokeswoman for the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office, said Williams was never a suspect in the Marshall fire investigation.

“He was someone that was staying on the property at the time and so was loosely associated with the property, so he was indexed along with everybody else, but never a suspect,” she said.

Failure to report

Sexual abuse of children is not condoned or allowed by the Twelve Tribes, former members said, but it does happen, and it is rarely reported to law enforcement when discovered.

Sometimes, a man accused of sexual abuse will be kicked out of the cult, ex-members said. But sometimes, he will be forgiven and allowed to stay. How a case is handled often depends on how much status the abuser has within the cult. Frequently, children who report sexual abuse are not believed; some are punished or told the abuse was their fault.

Anderson said she as a young girl told a woman she trusted about being sexually abused. That woman brought it to other adults, and Anderson was questioned by a male elder. She kept silent. Another elder’s wife then took her aside and questioned her.

“She said, ‘How do you have intercourse?’ And that is what threw me off. I said, ‘What is intercourse? And why would I have it?’ Then she said, ‘Is it anal or vaginal?’”

Anderson didn’t know what those words meant, and the elder’s wife concluded that she was lying about being abused in an attempt to get attention, Anderson said.

She still struggles to talk about it.

After escaping the group at 19, Post went to college and in his sophomore year poured out his heart in a 10-page letter to his father in which he detailed sexual abuse he’d suffered as a young teenager.

“He wrote me back and said, ‘I don’t believe anything in your story,’” Post said.

In a Twelve Tribes leadership meeting sometime around 2011, Wiseman asked why a particular case of alleged child sexual abuse wasn’t reported to outside authorities. Leaders told Wiseman that the girl’s father didn’t want to testify in court, Wiseman said.

He later followed up with the father, who said he was willing to work with law enforcement, but that a Twelve Tribes leader “told him not to testify because it would shame our Master’s (Jesus’) name,” Wiseman said, adding that the Twelve Tribes kicked out the accused abuser.

“It’s been sustained, spanning multiple eras in the Twelve Tribes, and they bury it,” the member who left in his 30s said. “They don’t advocate for the kids who are abused. They’re much more interested in their image than they are in protecting children.”

Inside the Twelve Tribes, sexual contact of any kind is forbidden outside of marriage. The punishment for young adults caught kissing or holding hands is marriage, ex-members said. Divorce is not allowed in the cult and interracial marriages are frowned on. Homosexuality is also forbidden; a 1990 teaching shared with The Post calls it “abominable,” and says gay or lesbian people “must be put to death.”

After co-ed education was banned, enough young men experimented with bestiality that Spriggs, the cult’s leader, in 2006 ordered young men to kill the animals they’d had sex with. At least 30 sheep, and several cows, goats and chickens were slaughtered, Wiseman said. He estimated around 10 men and boys confessed to bestiality around that time, both in the U.S. and abroad.

“That’s horrific psychological abuse,” Wiseman said. “These boys were repressed, not allowed to be normal kids, not allowed to talk to girls, and then when they confess their sin they’re made to go kill the animals.”

Pendergrass said the Twelve Tribes is about love, not punishment.

“Really all we are about, really, honestly, is loving people, loving our creator, loving our children and that’s really it,” he said. “All we know is if we love one another and we try to love everybody, it’s all going to work out. That might be kind of simplistic, but it sure does help me live a stress-free life and have lots of peace and be willing to do anything for love. That’s what I like.”

Periodically, the Twelve Tribes’ treatment of its children turns up in newspapers or TV news specials. In 2004, the Broward Palm Beach New Times in Florida published a story that featured an ex-Twelve Tribes member who said her husband molested her children and that the Twelve Tribes leadership denied her a divorce and attempted to cover up the abuse. She left the group, went to authorities and the man was convicted of sex crimes in 2006.

Around the same time, a criminal case was proceeding against a 25-year-old man after a 6-year-old girl told a child welfare worker the man fondled her in 2001, that story says.

In 2007, a former Twelve Tribes teacher pleaded guilty to molesting two boys in the 1990s, according to The Boston Globe. In Germany in 2013, 40 children were taken from a Twelve Tribes compound amid concerns of child abuse, according to a story in The Telegraph.

But abuse cases that lead to criminal charges are the exception, ex-members said, and many more allegations are handled behind closed doors within the Twelve Tribes.

“The only time they’d ever consider taking it to the authorities is if it was already leaked out and they had no choice,” the ex-member who lived in Boulder said.

When cases do garner publicity, the attention tends to quickly fade, and the Twelve Tribes continues operating unimpeded, ex-members said. Some find it frustrating to watch.

“We believe in religious rights,” Wiseman said. “But at some point, there needs to be discussion of where does the line come in when religious rights start to psychologically manipulate and abuse children. This is a bigger discussion that needs to be happening.”

High-profile betrayal

Around 2008, the Twelve Tribes learned that its founder’s wife, Marsha Spriggs, had carried out a series of extramarital affairs. Eugene Spriggs, the founder who died in 2021, ultimately decided his wife should be forgiven. The scandal rocked members’ faith in the group’s leadership.

“It wasn’t that she was a human and had fallen into sin, it was that she had personally been involved in sending away a lot of other families for much less serious infractions,” Wiseman said.

The affair revelations accelerated people’s departures from the group, and leadership at the Twelve Tribes responded by clamping down even more strictly on the dwindling number of families who remained.

In the past, followers could listen to traditional Irish music, go hiking or to the beach with their families on Saturdays, eat chocolate. Now, driving on Saturdays is forbidden, and Irish music and chocolate are banned. Women must part their hair in the middle; men must roll up their pant legs. Women can only wear dresses on weekends.

“It has slowly evolved into a very harsh, authoritarian-type of system,” the member who lived in Boulder said, describing the leadership’s reaction to the affairs as “total lockdown.”

Even before her husband’s death last year, Marsha Spriggs was the de facto leader of the Twelve Tribes, ex-members said, though the Tribes’ patriarchal organization would never formally reflect that.

And there were subtle signs that Eugene Spriggs may not have approved of everything his group had become, ex-members said. In 2012, a year before Wiseman left the cult, he confessed to Spriggs, who used the name Yoneq, that he drank beer with his wife, against the cult’s rules.

“He said, ‘Just don’t talk about it,’” Wiseman said.

The ex-member who left in his 30s said he met one-on-one with Eugene Spriggs as a teenager in the mid-1990s and told the man about horrific childhood abuse he’d endured in the Twelve Tribes. He said the founder wept silently as he shared the details of the abuse.

But after just five minutes, Marsha Spriggs burst into the room and sent the member out. She spoke to her husband briefly then cornered the member in the hallway.

“She comes out and says, ‘If you ever tell Yoneq anything like that again, I’ll send you (away from us) that day,’” the member said.

Years later, that member sneaked out of a Twelve Tribes commune in the middle of the night with a duffel bag of clothes. He waited in the bushes for a ride from a man who’d left the cult years before. That night, he slept on his friend’s floor.

In the morning, he woke up.

He drank a cup of coffee, forbidden in the cult.

And he realized he was, for the first time in his life, completely in charge of his own choices.

“I felt like I could float away,” he said. “That feeling, it’s impossible to describe. That feeling of freedom. And honestly, I feel some level of that every day.”